[The following essay by Jennifer Jihye Chun is included in the exhibition catalogue for “Waterscapes,” which will be available from the Richmond Art Gallery after October 28.]

Mainstream narratives commonly portray the experience of migration and settlement as a profound break from the past, compelling one to either adopt unfamiliar values and customs or fiercely protect an ethnic culture under siege. The everyday lives and sensibilities of immigrants, however, often defy such dualisms. While there are certainly ruptures and discontinuities, the migration experience is characterized as much by a joining together, as by a tearing apart, of lives, histories and affective attachments.

This joining together is a constitutive feature of place-making; it reflects a point of intersection among a vast, intricate and complex array of social processes and interactions. For the migrant, there is no “pure” place from which one leaves or to which one goes: “displacement occurs between contexts which are themselves already complex constructions.” The challenge, then, is to conceive of migration not simply in terms of a linear trajectory but as a dynamic and historically-contested set of meanings and practices that gain traction and resonance through space and time. In other words, it is through one’s experiences, aspirations and interactions with other people and the environment – not just the fixed geographies of national and geopolitical borders – that we learn what migration means and the forms it takes.

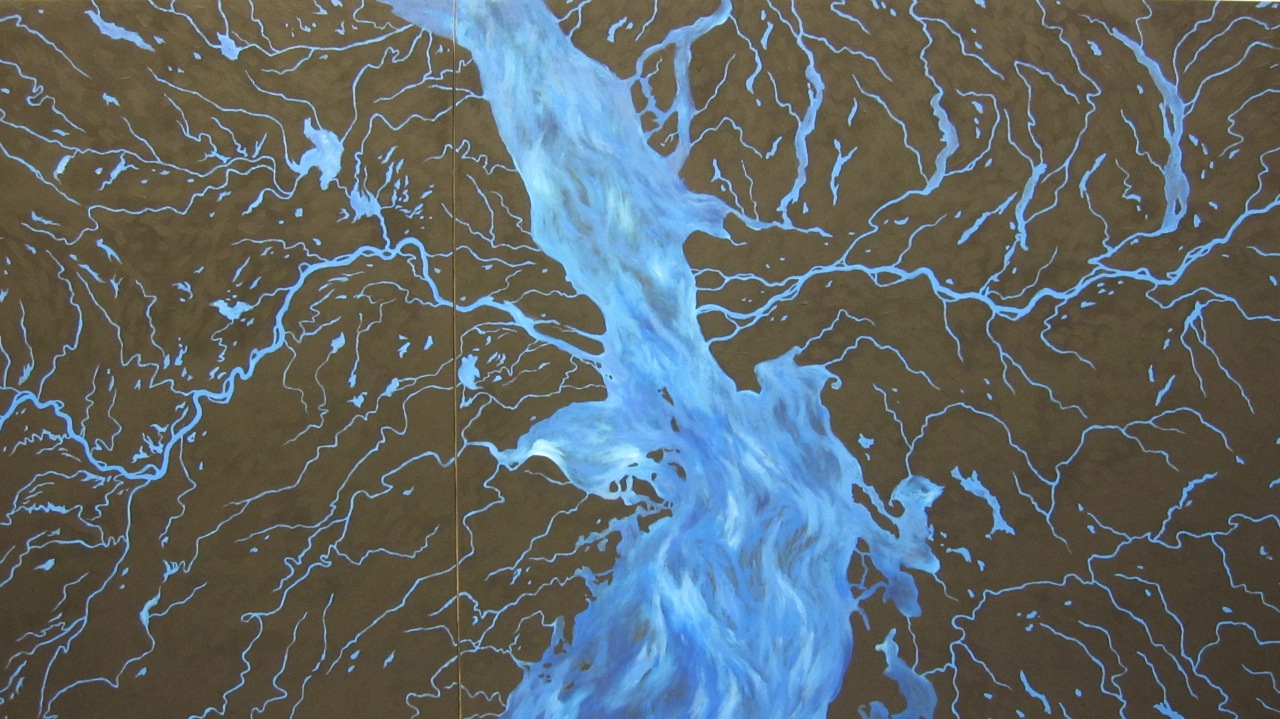

Gu Xiong’s connection to and experience of the water as a “metaphor of moving life” provide an alternative framework from which to construct a sense of place and belonging. Rather than illustrate the disjuncture between his life in Vancouver and his life in Chongqing – a distance separated by over 15,000 kilometers of oceans and rivers, Gu Xiong chooses to emphasize the points of fluidity and connectivity. It is in this “new space,” where boundaries are transgressed and new geographies are invented, where the possibilities of forging a new politics of place and migration are palpable and present.

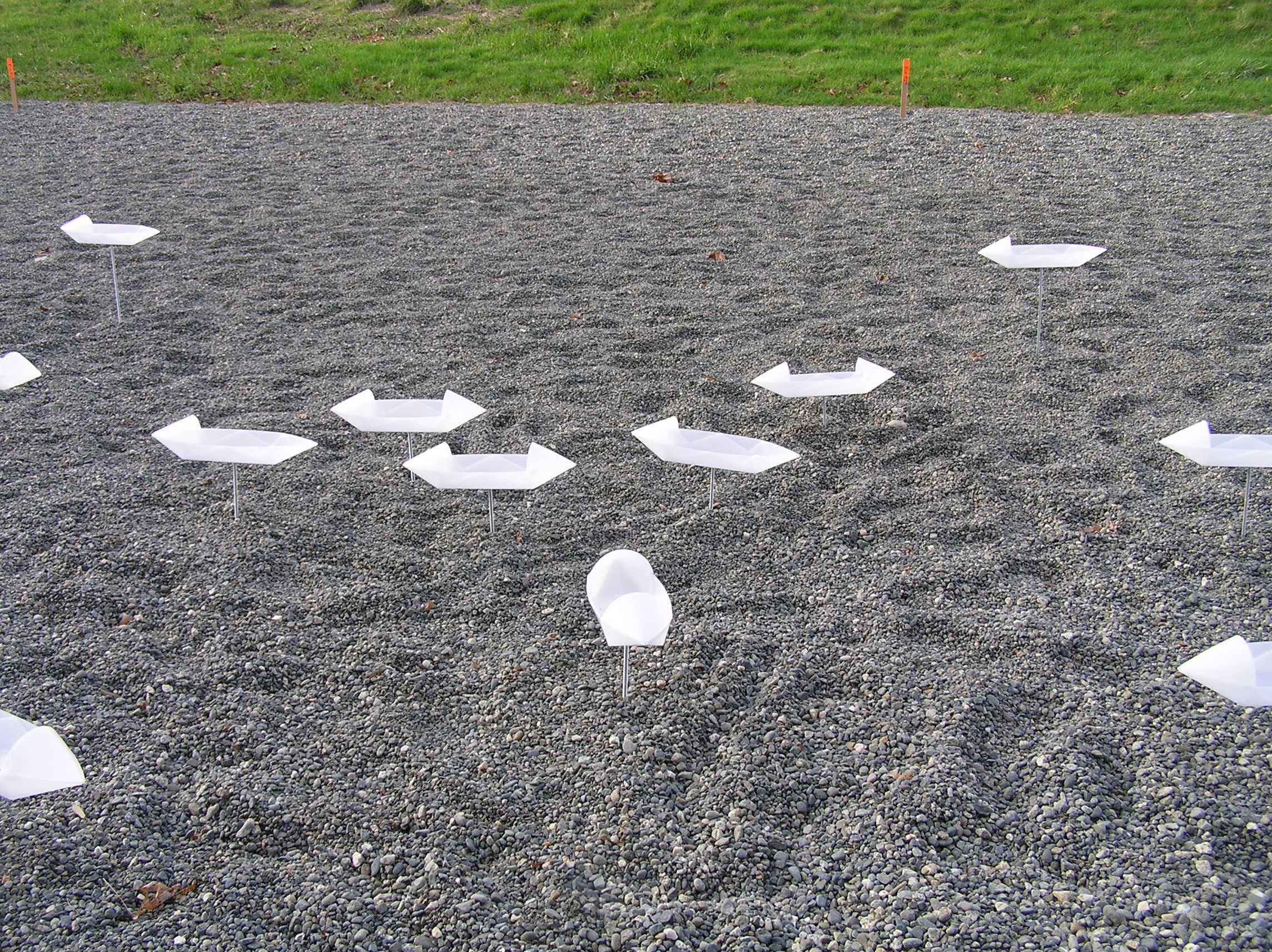

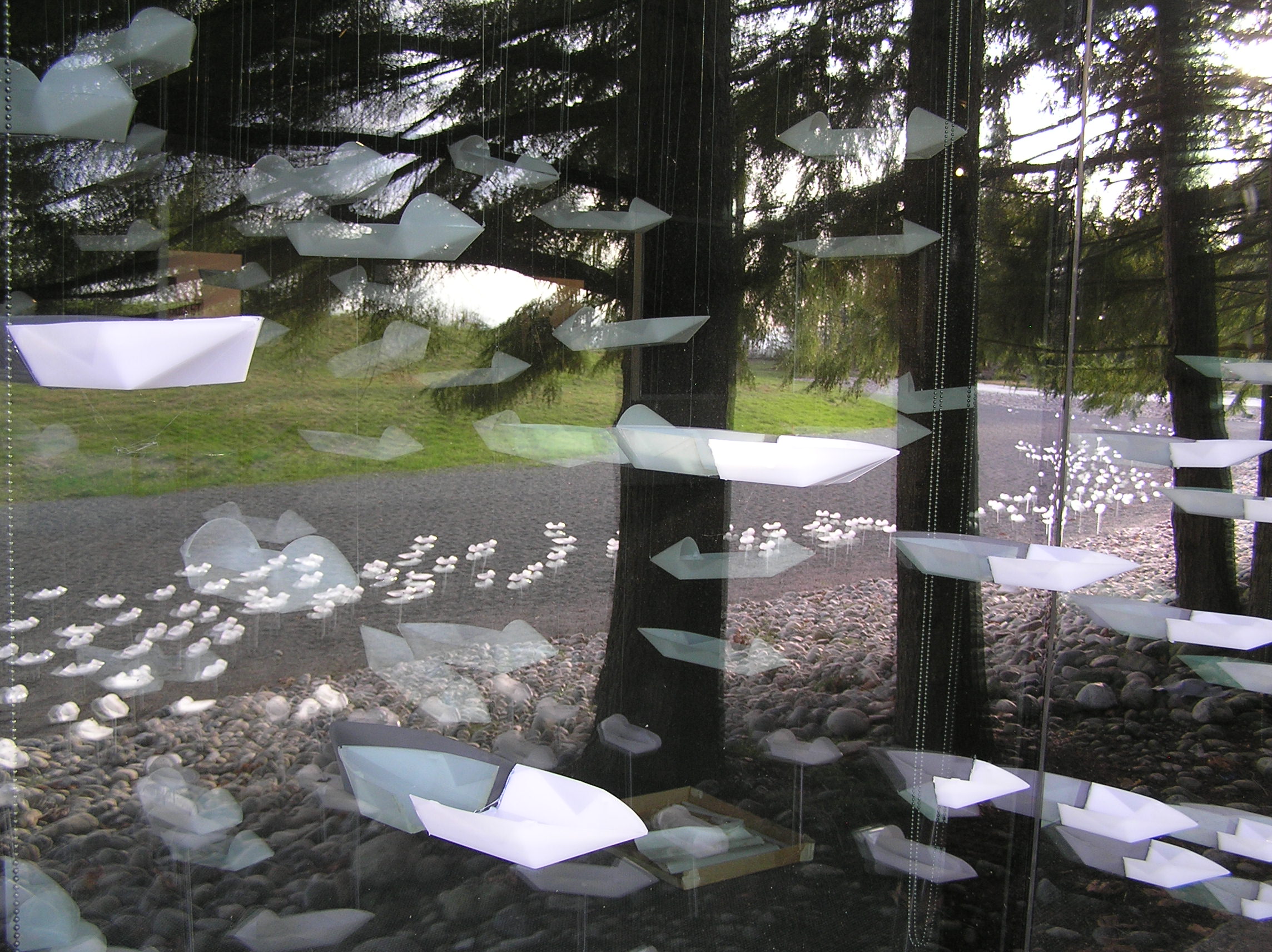

To bring the multiplicity of these changing forces in dialogue with the everyday experiences of migration, Gu Xiong’s art highlights the uneven relations of power, inequality and ecological destruction that profoundly shape our lives. Flanked on both sides of the seemingly endless procession of small white boats in Becoming Rivers, the first Waterscapes exhibit (UBC Museum of Anthropology, 2009-10), are photographic scenes of industry and manufacturing. While there are no images of people’s bodies or faces, they are hauntingly present in the images of the heavy, hazy fog that hang over the Yangtze River and the large piles of forested tree logs and cut timber that float on top of the Fraser River. Who lives and breathes in the polluted airs of Chongqing, a city that has grown from 8 million people in the 1980s to almost 32 million today? Who labours in the sawmills and pulp mill factories of British Columbia’s vast forestry sector? Which lands have been appropriated and from whom?

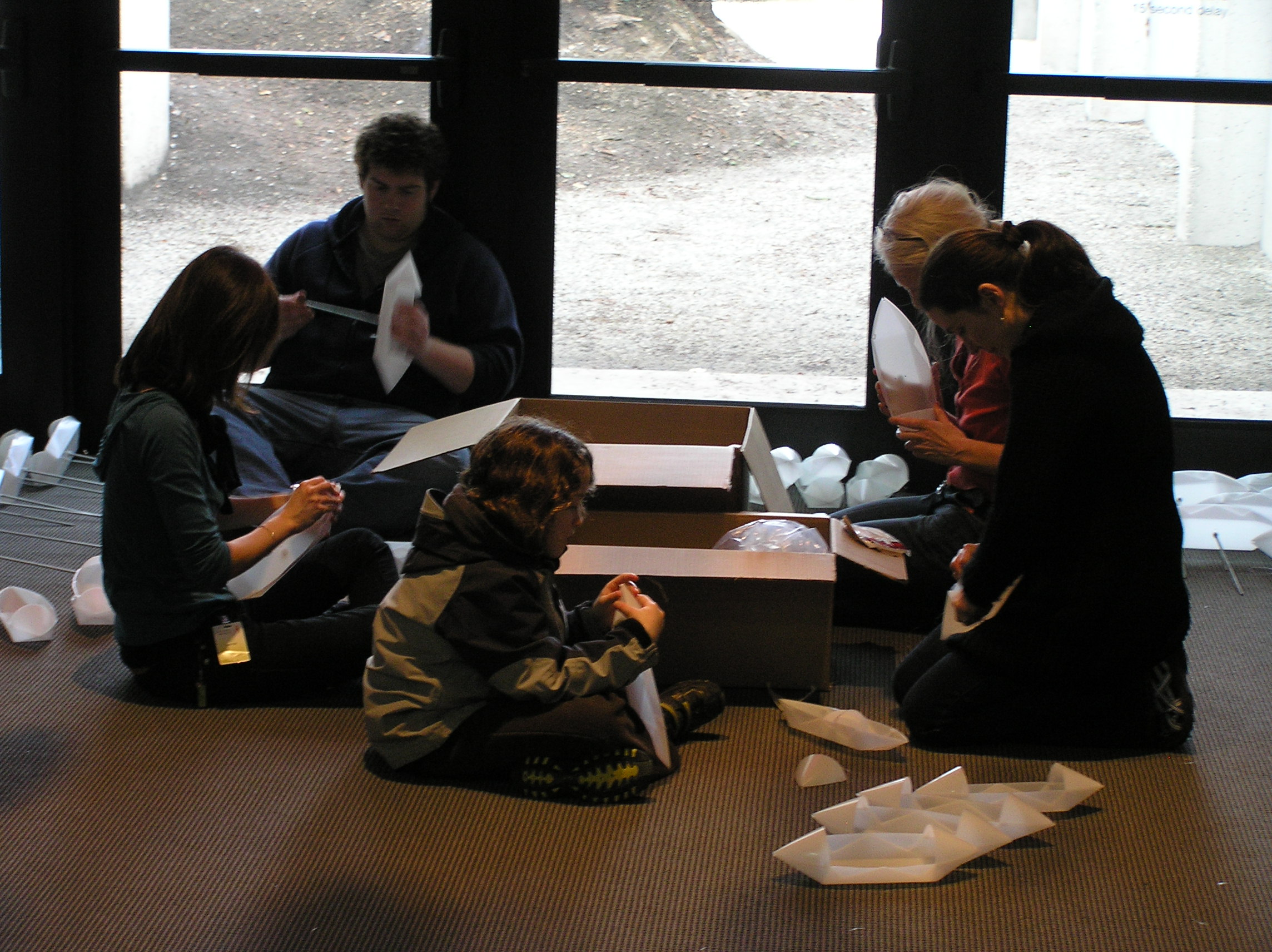

To begin to make sense of this haunting and bring migrants’ lives directly into view, the second Waterscapes exhibit shifts from the epic scene of 2000 identical boats floating through the large gallery spaces at UBC’s Museum of Anthropology to the more intimate setting of the Richmond Art Gallery. The arms of the Fraser River surround the city of Richmond, which has been transformed from a predominantly white European community to one of the most diverse and vibrant Asian communities in North America. In addition to providing an opportunity for Richmond residents to directly participate in the installation by folding and hanging their own white paper boats, this exhibit will feature video interviews with various people whose lives have been affected by the “changing forces” of the Fraser and Yangtze Rivers. Following are three vignettes from the video interviews:

Vignette 1: “Living in a basement”

Gu Xiong and his wife, Ge Ni (Jenny), his wife, experienced severe underemployment after migration. Ge Ni gave up a “very good job in China as an accountant” to work as a food and beverage server. She is still employed as a cashier and server at a food vendor at the Vancouver international airport – a job that gives her the opportunity to get out of the house and meet new people as well as brings her face-to-face with intolerant customers that berate her English accent. The hardships associated with low-paid work are not devoid of joy, but they recast the meaning of migration from a universal experience of opportunity and upward mobility to a vexed moment in one’s lifecycle when external conditions create pressures to uproot oneself and one’s family. Ge Ni’s response to Gu’s question about the natural beauty of Vancouver captures this experience: “It’s just like a basement. It doesn’t matter how beautiful [Vancouver] is, it doesn’t belong to us.”

Vignette 2: The “Iron Woman”

Dr. Ying Ying Chen is an archeologist from China who has spent every summer since 1991 in Barkerville, BC. She calls herself an “iron woman” for she is the only female archeologist who has dared to spend each hot summer in British Columbia’s interior, not only as a committed researcher but also as a public historian. Ying Ying runs daily tours about the Chinatown section of Barkerville. She warns tourists: “Our tour will be different from the European tour. On that tour, all the guides are professional actors. On this tour, I will talk about Chinese history.” Her emphasis on genuine historical depiction, as opposed to historical fiction, is part of her political intervention into the telling of BC’s history – a history that has not only systematically erased the presence of Chinese Canadians but has largely misrepresented them.

Vignette 3: The Bang Bang painter

Tian is a rural migrant who has struggled to survive for 21 years in the city of Chongqing as a porter (bang bang) and nude model. Tian’s daily wages are meager, allowing him to rent an apartment that functions mainly as a “shelter” from the harsh elements of wind and rain. He talks about the extreme loneliness he feels living apart from his wife and children with only a mouse and the sound of water to keep him company. Although he never had any formal art training, after twenty years posing as a nude model for aspiring young artists, he began to paint. His tiny one room apartment is crowded with large canvasses and brushes as well as a few simple pots and pans and an extra change of clothing. The pride he feels about his work is evident in the sense of confidence and satisfaction he has gained from receiving critical recognition for his paintings, including being chosen as a candidate of the “10 Most Inspirational People of Chongqing.” Tian asks, “Who would have ever thought that a bang bang would become associated with art in any sort of way?”

As vignettes these interviews are necessarily limited. Yet, as encounters mediated by the motivations and interests of the artists and scholars involved in Waterscapes, they are a central part of crafting an alternative politics of place, informed as much by our social interactions as by our efforts to transform the symbolic and material worlds. It is through one’s work and labour that we begin to see the inequities and inequalities that are so pervasive to the migration experience come into focus as well as the sense of self-worth and dignity that people cultivate to prevail over them.