Each student will be assigned a section of the novel Green Grass Running Water (pages will be divided by the number of students). The task at hand is to first discover as many allusions as you can to historical references (people and events), literary references (characters and authors), mythical references (symbols and metaphors).*

*Though I was assigned to pages 288 – 296, in my copy of the novel, that section aligns with pages 383-395, and all references will be in line with my version.

Brief summary of the section: The section of Green Grass Running Water that I was assigned can be split into three distinct parts. In the first part, Dr. Joe Hovaugh and Babo discover their car has gone missing while they are on the hunt for the Indians. Babo signs the two up for a bus tour of a local dam in order to continue their search. In the second section, I tells the story of Old Woman and Young Man Walking on Water to I. In the third section, Alberta stands out in the rain, is soaked and nearly hypothermic, and she is warmed by Latisha with a hair dryer in the restaurant, where they discuss pregnancy. Because we as a class have already discussed Coyote, my focus will be primarily on the relationship between Dr. Joe Hovaugh and Babo, which I think is pretty interesting.

As Flick states, Hovaugh is a play on Jehovah, and acts as an authority figure who “is more interested in contemplating his garden than in most other things. Note Gen. 1:31 ‘And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good'” (Flick 144). Babo, as Flick notes is the main character in Melville’s “Benito Cereno”, where he is “the black slave who is the barber and the leader of the slave revolt on board the San Dominick” (Flick 145). The Babo in Green Grass Running Water is overtly related to the Babo in Melville’s story, as she mentions that her great-great-grandfather worked on ships:

‘Did you know that my great-great-grandfather was a barber?…Cut hair. Shaved faces with the best of them. He worked on ships.’

‘Cruise ships?’

‘Something like that, said Babo. (King 348-349)

There are many instances throughout the text that compare Hovaugh to a slave-owner/explorer/colonizer/sailor and Babo to his slave. One explicit example is when Hovaugh is told to register Babo when they cross into Canada, as “all personal property has to be registered…for your protection as well as ours” (King 260). Neither Hovaugh or Babo remark on this objectification, making it evident that both are aware of their colonial relationship.

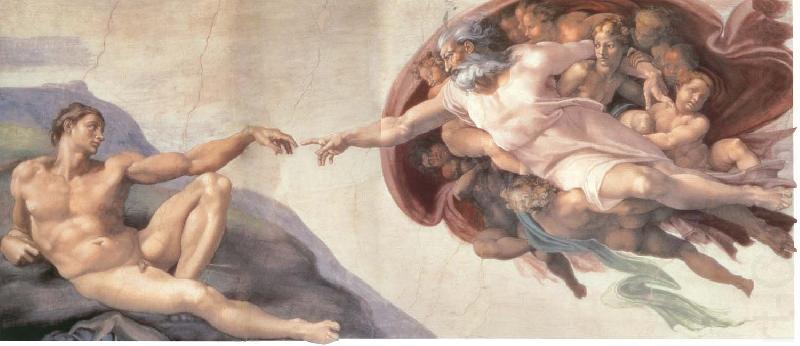

Flick notes that the three cars that go missing, the Nissan, the Pinto, and the Karmann-Ghia, the latter of which Hovaugh drives, are plays on the ships of Columbus named the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria (Flick 146), which correlates Hovaugh with the role of colonizer/conquistador. Columbus himself commanded the Santa Maria, which leaked and became sunken and lodged in a reef. This is similar to Hovaugh’s Karmann-Ghia, which, as a convertible (a play on words with colonial Christian conversion of Native peoples), is prone to leaks, and which Hovaugh and Babo are concerned about with storms on the horizon, furthering the ship comparison. Lastly, as the car disappears, leaving nothing but a puddle (King 390), Hovaugh and Babo’s vessel is seemingly overpowered by water, similar to Columbus’ Santa Maria.

All three parts of the section I was assigned deal with water (Alberta is soaked in the rain, Babo and Hovaugh sign up for a tour of a dam, I tells a story about water), and Coyote notes that “all this water imagery must mean something” (King 391), which tells the reader that we need to pay attention to the subtleties of King’s water usage.

Hovaugh forces Babo to do all the work in finding a new ride (furthering the slave comparison), and when he returns to see what she’s found, she tells him that the coffee shop they’re at has “some great cinnamon tea” (King 384). Both cinnamon (as a spice) and tea leaves were brought to Europe by “explorers”/conquistadors. Instead of finding a new car, Babo signs the two up for a bus tour of Parliament Lake and the Grand Baleen Dam (King 385). As Flick notes, the Grand Baleen is a play on the Great Whale (or Grand Baleine) river project, in which “massive diversions of water…destroyed traditional Cree hunting territories” (King 150), illustrating the devastating effects of colonialism, and directly contradicting King’s title of Green Grass Running Water, because a dam ensures that the grass on the other side isn’t green and the water is stilled. Parliament Lake’s name can also be noted as a jab at white government and how it unfairly treats Native peoples in Canada, as well as how Canada’s system is derived from British/colonial ideals.

Finally, and perhaps most obviously, Babo and Hovaugh sign up for an exploration of this dam in order to see the countryside and “spot the Indians” (King 385), a reference to the “explorers” (a guilt-free way to describe colonizers) of the New World.

I’m sure I missed a lot of the references within this passage, and would love to hear other people’s thoughts, and I wish that I could have gone into more detail about the Coyote section and Alberta’s section, but that would be way too long for this blog post and I found the Hovaugh/Babo relationship to be the most fascinating. Overall, King’s work was really interesting to read, and though it was frustrating to know I likely missed many of his allusions, it was intriguing and refreshing to read a book where the majority of the meaning is hidden from the reader.

WORKS CITED

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. July 09 2015.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1993. Print.

Maclean, Frances. “The Lost Fort of Columbus.” Smithsonian. Smithsonian.com, 2008. Web. 09 July 2015.