Image via Clip Art Panda.

Wow. Where do I begin? My journey of learning in LLED 462 has been phenomenal. When I first began the course, I wasn’t entirely sure what the learning curation was or how much it would really impact me, as an individual and as a teacher-librarian. Now, as we round the corner to its completion, I feel truly fortunate to have a) gotten into this course and b) for having this learning curation, in a way, lead (and empower) me in my learning.

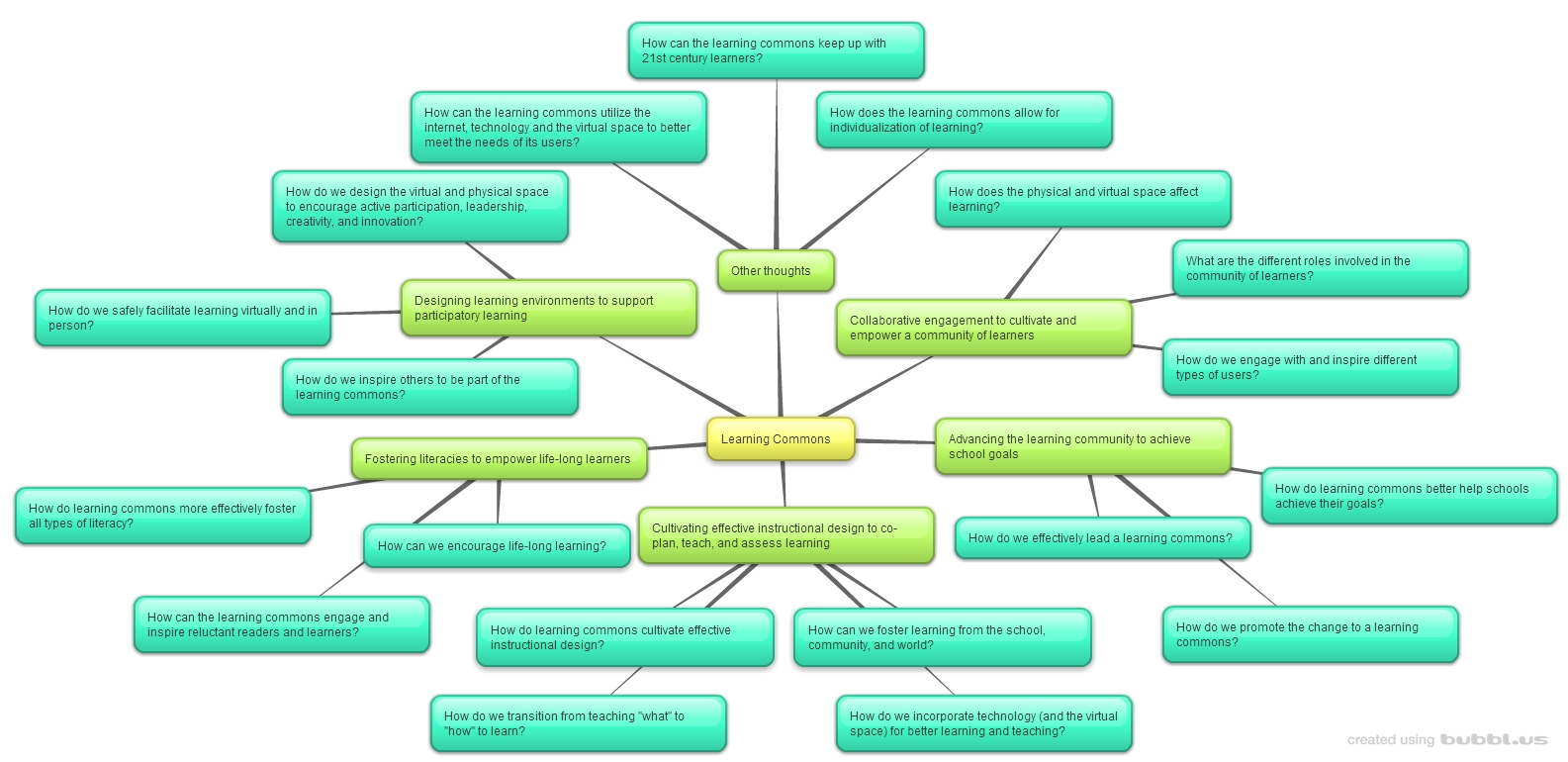

Initially, I was uncertain as to what my essential question should be – it seemed a bit overwhelming. I had so many questions and ideas percolating in my mind that I had no idea how I was going to narrow it down to one leading question. I remember deciding to just jot down my ideas on a piece of paper, simply letting the words and thoughts in my mind flow. With these thoughts in mind, I decided to take a break to read Leading Learning and IFLA School Library Guidelines. As I read, the five standards, which “focus on key concepts to be implemented to drive best teaching and learning” (CLA, 2014, p.8), really stood out to me. My current library seemed like such a far stretch from these amazing standards and vision for school libraries (learning commons). Because these standards included a growth continuum that could lead one from library to learning commons, I knew immediately that my essential question needed to stem from them. Consequently, I decided to brainstorm questions related to each of the five standards. You can see my brainstorm below:

Clearly, I had a number of potential essential questions to consider. Before I selected one, I decided to outline my goals for the course. If I had goals in mind, then my essential question would therefore become a lot clearer. The goals I narrowed down were the following:

- To be able to justify to my administrator why we should transform the library into a learning commons

- To be more effective at my role as teacher-librarian

- To gain a better understanding of the different types of literacies and how to teach them more effectively

- To better utilize and explore the digital world/technology and apply them to my role as a teacher-librarian

As I stated in my initial learning curation, my goals were purposely broad, because they were meant to help me grow in many was both as a teacher and as a teacher-librarian. With these goals in mind, I finally decided on an essential question, knowing full well that it may change, develop, or evolve as the course progressed. My essential question was: How do learning commons better help schools achieve their goals? Again, I chose this question, because it directly helped me achieve my personal goals. If I could demonstrate how learning commons help schools achieve their goals, then I can better advocate to my administrator why our library needs the appropriate funding to transform into a learning commons. Furthermore, to take on a learning commons model to improve school goals, I must figure out how to be more effective at my position, which would thus entail gaining a better understanding of different literacies and embracing and understanding the digital world and technology. In essence, my essential question drove my goals.

As my learning for this course comes to a close, then, did my essential question stay the same? Did it truly drive my goals? Yes.

I initially thought my essential question would change, yet, as I made my way through the course, I realized that my essential question continually held much power and drive in my learning. I honestly do not think I could have chosen a better question to lead my learning. Remarkably, every module and every assignment applied to my essential question, and, consequently, to my personal goals. To wrap up my learning curation, I thought it would be nice to review the modules and connect them to my essential question.

Image via By The Brooks.

Although Module 1 mainly focused on preparing us for the course and narrowing down an essential question, the readings, as mentioned above, truly resonated with me. As I’ve explained previously, my school’s perception of the library has been a bit “discolored.” Due to lots of teacher-librarian changeover, and, as a result, little consistency in the school library, the concept and role of what a teacher-librarian is, does, and how they impact the school has become, in a way, forgotten. Thus, when I was reading Leading Learning, I felt empowered. It provided me with a guide to implementing change and a renewal for the school library (learning commons) that will help the staff and school perceive the library and the teacher-librarian in a new light. I loved that the standards were spread out as a continuum so that I could easily see where my current library is and where it needs to go. In addition, it nicely laid out key steps for implementation. Not only did it inspire my essential question, but it provided me with a crucial way for getting my current library geared up to become a learning commons, so that I can help my school achieve its goals.

I felt that Module 2, School Libraries as Places for Literacy and Learning, directly spoke to my essential question. Sulivan and Lunny (2014) specifically state, “The Learning Commons is the ‘Implementation House’ for school, district, and ministry goals” while Leading Learning (2014) quotes, “Over twenty years of research shows that student achievement and literacy scores advance where professionally staffed and resourced school libraries are thriving” (p. 4). In other words, having a properly implemented learning commons directly increases student achievement, which thus directly improves school’s goals. Not only does implementation matter, but having an excellent rapport, learning commons’ team, and a strong basis for collaboration is pivotal to a learning commons running effectively and thus helping schools achieve their goals. As Hayes states in Library to Learning Commons (2014), “[I]t is great staff, not great stuff, which is the hallmark of a thriving school library learning commons.” It emphasized to me how important it is that the school works together as “team,” that the school spends time collaborating, taking ownership, reflecting, and celebrating. When this “recipe” comes together, students learn how to learn, which results in higher level thinking and higher school achievement.

Image by Trish_Gee88 via imgfave.

I was able to connect with Module 3, Cultivating Life-Long Reading Habits, in so many different ways. Growing up, I loved reading. In retrospect, I believe it was because my mother encouraged my free voluntary reading, even though it wasn’t necessarily the highest literature that I was selecting (i.e. Archie comics). The scenarios for the discussion and learning curation really bothered me, not only because I know they happen routinely, but because I could imagine what could have happened to me as a child if I hadn’t been allowed to follow my own interests in reading. [As a side note, my 8 month old baby daughter is already participating in her own free voluntary reading. She’ll crawl over to our bookshelf and select the books she wants to read or wants me to read to her. She tends to always pick the same ones (The Seals on the Bus, Little Blue Truck, Color Dog, and anything Pete the Cat). It’s so amusing watching her babble to herself as she flips the pages!] The readings, however, truly reinforced to me, as my role of teacher-librarian, how crucial it is that I ensure that students be allowed their freedom to choose what they want to read and to have the pleasure to read what they want. As Gaiman (2013) states in his lecture, “Do not discourage children from reading because you feel they are reading the wrong thing…Well-meaning adults can easily destroy a child’s love of reading: stop them reading what they enjoy or give them worthy-but-dull books that you like, the 21st century equivalents of Victorian ‘improving’ literature. You’ll wind up with a generation convinced that reading is uncool and worse, unpleasant.” Free voluntary reading is so crucial for students not only to keep them reading, but also in helping them attain higher achievement in a variety of areas. As Stephen Krashen (2012) points out in his Power to Reading video, free voluntary reading is the source of our reading ability, most of our vocabulary, our complex grammatical construction, spelling, writing, writing style, and knowledge of the world. Being the teacher-librarian in a learning commons, I can therefore encourage free voluntary reading and help educate others about its importance (i.e. in discussions, on the website, in newsletters, etc.), which helps to build a schoolwide reading community where students become motivated to read. If students are motivated to read, they will therefore gain the literacy benefits associated with free voluntary reading, which will undoubtedly help to better meet school goals in literacy.

Module 4, Learning from Multi-Modal Texts, emphasized to me how critical it is to ensure that my definition of literacy expands to include various forms of text, not just print materials. The readings pointed out how literacy now includes things such as images, video, audio, design elements, and hypertextual elements (Serafini & Young, 2013; Dalton and Grisham, 2013). The readings, in a way, helped redefine my definition of literacy from simply reading and writing to the ability to read, navigate, interpret, comprehend, think critically about, analyze and produce (write/create) a variety of texts (for different purposes) regardless of the format (Serafini, 2012). As Dalton and Grisham (2013) point out, “There is a growing body of research demonstrating the positive effect of multimedia on learning, including promising evidence that composing in different modes can engage students in content and develop their literary analysis skills” (p. 220-221). Yet, they (2013) caution, “Keys to success are use of the tool in service of a meaningful literacy activity and not the tools themselves” (Dalton and Grisham, p. 224). With emerging technologies, we need to teach the necessary skills for students to be able to do these things in whatever format they are using (Serafini, 2012; Serafini & Young, 2013) while remembering to not simply use technology to use it, but to always use it with a purpose and with my students’ learning in mind. If I can effectively integrate technology and multi-modal forms of text into my teaching in the learning commons, then students will gain a better understanding of what they are learning, which will therefore help schools meet their goals.

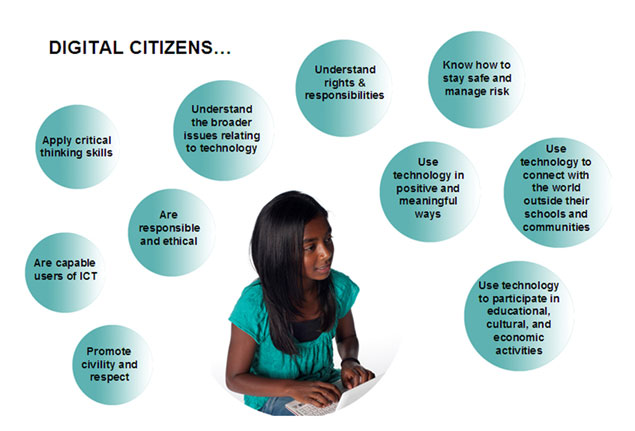

Image via MediaSmarts.

Module 5 and 6, Critical Literacy and Digital and Media Literacy, further expanded my definition of literacy to include multiple literacies, such as those discussed in the modules (in addition to others, such as transliteracy and cultural literacy). Although I had heard of critical literacy before, I found myself using it interchangeably with critical thinking. These readings helped clarify the difference for me. From the readings, I learned that critical literacy was the ability to view the world through a critical lens by actively reading, viewing and observing; reflecting and critiquing what you are reading; actively constructing knowledge; and gaining awareness of techniques used to influence readers, so that they can challenge norms by questioning, analyzing and challenging power, inequality and injustice; being aware of bias, hidden agendas, and underlying messages; reflecting on the authors purpose; and understanding and embracing different viewpoints (Coffey, n.d.; Farkas, 2011; Hayes, 2014; Matthews, 2014; Roberge, 2013). It, in essence, helps students think differently, gain a deeper understanding, build empathy, and inspire them to take social action (Coffey, n.d.; Farkas, 2011; Hayes, 2014; Matthews, 2014; Roberge, 2013). Meanwhile, digital literacy “encompasses the personal, technological, and intellectual skills that are needed to live in a digital world” while media literacy is “critical engagement with mass media” (MediaSmarts, 2015). Despite having different definitions, these literacies, along with the others, are all interconnected and necessary for students to develop the 21st century skills needed to be life-long learners in our world. These literacies, therefore, are things that I need to incorporate into my everyday teaching by facilitating and scaffolding activities so that students can construct their own knowledge and apply these skills and learning. By incorporating critical literacy, students will have a deeper understanding of different perspectives, question motives, and think more critically, while integrating digital and media literacy will help students develop higher critical and creative thinking in connection to ICT. As a result, we will help schools achieve their goals, because students will be able to think more critically and creatively, use technology more effectively and ethically, and apply their learning in new and innovative ways. This will naturally transfer to helping schools meet their goals, since students will have the skills and mindset to apply their learning in more advanced and higher level ways.

Image by Jonny Goldstein via Flickr.

Module 7, the Teacher Librarian as Educational Leader, reignited the spark in me to ensure that I get my staff back on board to perceiving the teacher-librarian in a new light, as a collaborator and an educational leader. From the readings, I realized that it all starts with building key relationships and rapport with my school, staff, and community. As Cooper and Bray (2011) state, “In the end, school library media is at its heart a people business.” Being proactive, flexible, adaptable, friendly, and sociable were key themes throughout the readings. I cannot just sit back and hope that people come to me for instructional leadership or collaboration; I have to go out of my way to model and encourage this. I have to ensure my learning commons is welcoming and comfortable, participate in a variety of projects, clubs, and committees, lead professional development sessions, and make collaboration purposeful, engaging, and helpful (Canter et al., 2011; Cooper and Bray, 2011; Diggs, 2011). Not only that, but I must have a solid knowledge of the curriculum, develop and manage quality resources, network with other schools and libraries, and know the needs of my users (Canter et al., 2011; Cooper and Bray, 2011; Diggs, 2011). If I do these things, the school and staff will see not only me in a new light, but also the library learning commons. As the readings point out, collaboration with the teacher-librarian has been linked to increasing student achievement in the school (Canter et al., 2011). Thus, if I create an environment that is conducive to collaboration, then students will gain higher levels of achievement, which will consequently better help schools meet their goals. Not only that, but as I stated in my module 7 learning curation: Teacher-librarians themselves, as the head of learning commons, take on multi-faceted roles, such as teacher, instructional partner, information specialist, and program administrator (Cooper & Bray, 2011). They pilot new ideas, try out new technologies, and help others learn and master new teaching styles and technologies so as to meet the diversity of our learners. They need to know their users’ needs (staff, students, parents) and make creative use of their time to better meet them. When teacher-librarians embrace all these facets of their job, are proactive, and strive to do well, then they will help make their learning commons a powerful place of learning which will have significant positive impact on their users (and consequently the goals of the school).

Image via Shemeen Basit.

Module 8, Supporting Literacy with Learning Technology, reminded me of the importance of using technology purposefully, so as to engage students, support their learning, and help them develop new and multiple literacies (Asselin & Moayeri, 2011). What really stood out to me in the readings was that although many teachers are using Web 2.0 applications, most are being used in a 1.0 consumerist way (Asselin & Moayeri, 2011). If we want to really use these tools effectively, then we need to embrace them in the more interactive, “mindset two” way that encourages participation, distributed expertise, collective intelligence, collaboration, sharing, innovation, and evolution (Asselin & Moayeri, 2011). When used effectively and implemented properly and purposefully, we can better take advantage of the higher level thinking and participatory nature these tools lend themselves to. As the teacher librarian in a learning commons, I can therefore model use of these tools for teachers, conduct professional development sessions on their use, collaborate with staff on them, and use them properly with students. If I do these things, students will develop higher level thinking, which will result in greater achievement thus resulting in schools achieving their goals.

Module 9, Supporting Learners as Inquirers and Designers, highlighted ways to get students to come into the library, to learn, collaborate, and create. As a learning commons, the library is flexible, engaging, and welcoming to students (including those at risk!). As Loertscher (2014) points out in his article, the learning commons transforms the library into “a giant learning laboratory” where users explore, create, participate in, perform, and command their own learning (p. 35). I would love to create an environment that is conducive to this learning, where students can come to think, play, tinker, experiment, and create, where they feel confident and comfortable learning independently and collaboratively, and where they feel empowered and supported (mentored) by staff. If we can do this, then we will most definitely help schools meet their goals.

Image by 5chw4r7z via Flickr.

Module 10, Supporting Diverse Learners and Creating Opportunities in the Library, brought many ideas for helping support diversity and diverse learners in our learning commons. As teachthought (2014) states, “Student-centered learning is a process of learning that puts the needs of the students over the conveniences of planning, policy and procedure….[and which] uses an actual person as an audience, and designs learning experiences backwards from that point.” If the learning commons can focus on the needs of its users and builds learning from this, then we will help students grow, learn, and develop. Not only that, but by creating opportunities (i.e. provocations, clubs, resources, makerspaces, etc.), a place to go (for comfort and security), and by providing adaptations to meet the needs of our users, we create learning opportunities and environments that help students further learn more deeply and in the best format/way for them. All of these factors contribute to students gaining higher achievement which results in schools consequently achieving their goals.

Module 11, which focused on Social Justice, made me better aware of how I, as the teacher-librarian, can address issues of social justice by carefully selecting resources, topics, and creating collaborative plans. As Danielle McLaughlin (2014) writes:

“I believe that we teach justice by actively and purposely engaging those whose views differ from our own. We must do this consciously and creatively. We must invite disagreement, but also acknowledge that all points of view are not equally valid or justifiable. But if we find everyone to be in agreement, if we quickly find a consensus, we should acknowledge that someone must be missing. Whose voice is not being heard? We need to actively seek out views that contradict our own, or we may never truly understand our own views.”

Wow. McLaughlin’s article blew me away. I had never really thought about how important it is to seek views that contradict our own and what the consequence is if we find that there are no conflicting views. Teaching social justice isn’t an “easy” thing, it takes many forms and applies to a multitude of different contexts. Yet, if we can help our students think critically and work towards addressing inequalities, then we are one step closer to higher, more active learning, processing, and application.

Image via Nadha Hassen.

Finally, Module 12, which focused on advocacy for school libraries, was a nice finishing touch and a wrap-around for my essential question. The whole purpose of my essential question is so that I can advocate for my library, so it was fitting that this was the final module in the course. I enjoyed Stephen Krashen’s (2014) defense of libraries, particularly when he pointed out how higher reading scores are directly correlated with a better school library and more school librarians per child and how access to a school library of 500 books or more balances the negative effects of poverty. Clearly libraries and teacher-librarians play a pivotal role in students’ reading. As Dianne Oberg (2014) states, “Four decades of research indicates that well-staffed, well-stocked, and well-used libraries are correlated with increases in student achievement.” Yet, as Oberg (2014) points out, a school library isn’t the only aspect that brings about these improvements, it also requires collaboration, inquiry, engaging cultural experiences, knowledge, innovation, and access to diverse resources, which are all at the heart of a learning commons. These are direct quotes, coming from reputable sources, that I can use to advocate for my library to gain more funding and to transition to a learning commons. Clearly, if the library is transformed into a true learning commons and is funded appropriately, then it will directly improve the school’s literacy goal on reading, since studies have shown that it is directly correlated.

Thus comes the end of my (current) learning curation (but not the end of my learning). Each module, in a way, has helped to build my case and advocacy to transform my current library into a learning commons and has helped me meet my initial goals. First, each module has helped me better justify to my administrator how a learning commons not only helps to improve school goals, but helps build a stronger school community. I have countless articles, quotes, and explanations as to why a learning commons is necessary in our school. Second, I feel that I will now be more effective at my role as teacher-librarian, because I have so many more tools to use and knowledge of how to more effectively meet my users’ needs. Third, I have a much better understanding of different literacies, particularly new literacies and critical literacy. Fourth, I feel much more competent in not only using technology, but using it purposely and effectively. From Assignment 2, I have a literacy plan that I am eager to bring to my administrator when I return to work from my maternity leave. From Assignment 3, I have a way to showcase to my staff my role not only as instructional leader, but as a collaborative and instructional partner. All in all, I am not only a more knowledgeable and capable teacher-librarian, but I am much more empowered and able to make the changes necessary to help my school and students become higher learners, critical thinkers, and active and engaged participants/creators in their own learning.

References:

5chw4r7z. (2015). [Image of Makerspace]. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/5chw4r7z/15756583153

Alberta School Library Council. (n.d.). Web 2.0 tools. Retrieved from http://aslc.ca/for-teachers-teacher-librarians/toolkit/digital-literacy/

Asselin, M., Abebe, A. & Doiron, R. (2014). Applying an ecological model for library development to build literacy in rural Ethiopian communities. Proceedings of the International Federation of Library Associations Annual Conference, Lyons, France.

Asseslin, M. & Moayeri, M. (2011). Practical strategies: the participatory classroom: web 2.0 in the classroom. Literacy learning: the middle years, 19(2), i-vii

Barack, L. (2014, May 1). LGBTQ & you. Retrieved from http://www.slj.com/2014/05/diversity/lgbtq-you-how-to-support-your-students

Basit, Shemeen. (2012). [World of Web 2.0]. Retrieved from http://shemeenbasiteism-animoto.blogspot.ca/2012/04/what-kind-of-people-use-web-20.html

BC Ministry of Education. (2012, October 17). Developing digital literacy standards. Retrieved fromhttp://engage.bcedplan.ca/2012/10/developing-digital-literacy-standards/

Bird, E. (2014, August 1). Wikipedia, Amelia Bedelia, and our responsibility regarding online sources. Retrieved fromhttp://blogs.slj.com/afuse8production/2014/08/01/wikipedia-amelia-bedelia-and-the-responsibility-of-online-sources/#_

Clip Art Panda. (2014). [Image of Smiley Face with Thumb up]. Retrieved from http://www.clipartpanda.com/categories/smiley-face-thumbs-up-thank-you

Davis, H. (2010, February 3). Critical literacy? Information! Retrieved fromhttp://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2010/critical-literacy-information/

Farkas, M. (2011, November 1). Critical inquiry in the age of social media. Retrieved fromhttp://www.americanlibrariesmagazine.org/article/information-literacy-20

Brunelle, C. (2014, May 1). Everyday diversity: A teacher librarian offers practical tips to make a difference. Retrieved from http://www.slj.com/2014/05/diversity/everyday-diversity-a-teacher-librarian-offers-practical-tips-to-make-a-difference/

Canadian Library Association. (2014). Leading learning: Standards of practice for school library learning commons in Canada. Ottawa:ON. Retrieved from http://www.slj.com/2014/05/diversity/everyday-diversity-a-teacher-librarian-offers-practical-tips-to-make-a-difference/

Canter, L., Voytecki, K., Zambone, A., & Jones, J. (2011). School librarians: The forgotten partners. Teaching Exceptional Children, 43(3), 14-20.

Carmichael, S. (n.d.). Examining Island of the Blue Dolphins through a literary lens. Retrieved fromhttp://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/examining-island-blue-dolphins-1068.html

Coffey, H. (n.d.). Critical literacy. Retrieved from http://www.learnnc.org/lp/pages/4437

Cooper, O. P., & Bray, M. (2011). School library media specialist-teacher collaboration: Characteristics, challenges, opportunities. TechTrends, 55(4), 45-55.

Dambruoso, A. (2014, July 18). 10 things classroom teachers need to know about modern school librarians. Retrieved from http://libraryallegra.wordpress.com/2014/07/18/10-things-classroom-teachers-need-to-know-about-modern-school-librarians/

Dembo, S., & Bellow, A. (2013). Untangling the web: 20 tools to power up your teaching. Thousand Oaks: CA. Retrieved from https://go.library.ubc.ca/nj78Kh

Diggs, V. (2011). Teacher librarians are education: Thoughts from Valerie Diggs. Teacher Librarian, 38(5), 56-58. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/875201232

Discovery Education. (n.d.). Web2014 Presentation tools. Retrieved byhttp://web2014.discoveryeducation.com/web20tools-presentation.cfm

Dressner, J., & Hicks, J. (2014, May 17). Why libraries matter. Retrieved fromhttp://www.theatlantic.com/video/index/371084/why-libraries-matter/

Gaiman, N. (2013, October 15). Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming?CMP=twt_gu

Goldstein, Jonny. (2012). [Image of collaboration]. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/jonnygoldstein/8161551606

Hassen, Nadha. (2014). [Image of advocacy]. Retrieved from http://nadhahassen.com/self-advocacy-allies/

Hayes, D. (2014, August 9). Let’s stop trying to teach students critical thinking. Retrieved from http://io9.com/lets-stop-trying-to-teach-students-critical-thinking-1618729143

Hayes, T. (2014, 54:3). Library to Learning Commons. Retrieved from http://www.cea-ace.ca/education-canada/article/library-learning-commons

Institute of Education, University of London. (2013, September 11). Retrieved fromhttp://www.ioe.ac.uk/newsEvents/89938.html

Grisham, D. (2013). Love that book: multimodal response to literature. The Reading Teacher. 67(3), 220-225.

Kang, C. (2014, March 5). Why all that time texting is good for your kids. A Q&A with author Danah Boyd. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2014/03/05/why-all-that-time-texting-is-good-for-your-kids-a-qa-with-author-danah-boyd/

Kelley, S., & Miller, D. (2013). Reading in the wild: The book whisper’s keys to cultivating lifelong reading habits. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kennedy, C. (2014). Tweeting kindergarteners? School Administrator, 7(71), 13. Retrieved fromhttp://aasa.org/content.aspx?id=34322

Konnikova, M. (2014, July 16). Being a better online reader. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/science/maria-konnikova/being-a-better-online-reader

Krashen, S. (2014, February 16). Dr. Stephen Krashen defends libraries at LAUSD board meeting. Retrieved fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAui0OGfHQY

Krashen, S. (2012, April 5). The power of reading, The COE lecture series, University of Georgia. Retrieved fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DSW7gmvDLag

Loertscher, D. V. (2014). Makers, self-directed learners, and the library learning commons. Teacher Librarian, 41(5), 35-35,38,71. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1548229909

McLaughlin, D. (2014). The King of Denmark and the naked mole rat: teaching critical thinking for social justice.Education Canada. 54(3). Retrieved from http://www.cea-ace.ca/education-canada/article/king-denmark-and-naked-mole-rat-teaching-critical-thinking-social-justice

MediaSmarts. (n.d.) Digital & media literacy. Retrieved from http://mediasmarts.ca/digital-media-literacy

Oberg, D. (2014). Ignoring the evidence: another decade of decline for school libraries. Education Canada, 54(3). Retrieved from http://www.cea-ace.ca/education-canada/article/ignoring-evidence-another-decade-decline-school-libraries

Pineda, I. (2013, May 25). Five questions about content curation. Retrieved fromhttp://blog.isaacpineda.com/2013/05/five-questions-about-content-curation.html

Roberge, G (2013, June). Promoting critical literacy across the curriculum and fostering safer learning environments. What works? Research into Practice, Ontario Ministry of Education. Retrieved fromhttps://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/WW_PromotingCriticalLiteracy.pdf

Serafini, F., & Youngs, S. (2013). Reading workshop 2.0: Children’ literature in the digital age. The Reading Teacher,66(5), 401-404.

Serafini, F. (2012). Reading multimodal texts in the 21st century. Research in Schools. 19(1), 26-32.

SLJ. (2014, May 1). Program diversity: do libraries serve kid with disabilities. Retrieved fromhttp://www.slj.com/2014/05/diversity/program-diversity-do-libraries-serve-kids-with-disabilities/

Sulivan, D., & Lunny, J. (2014, June 28). Imagine the possibilities. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_QnbQxnNCI

Teach thought. (2014, August 17). 4 principles of student-centered learning. Retrieved fromhttp://www.teachthought.com/learning/4-principles-student-centered-learning/

Trish_Gee88. (2012). [Image of Reading quote]. Retrieved from http://imgfave.com/view/2465455

Vangelova, L. (2014, June 18). What does the next-generation school library look like? Retrieved fromhttp://blogs.kqed.org/mindshift/2014/06/what-does-the-next-generation-school-library-look-like/