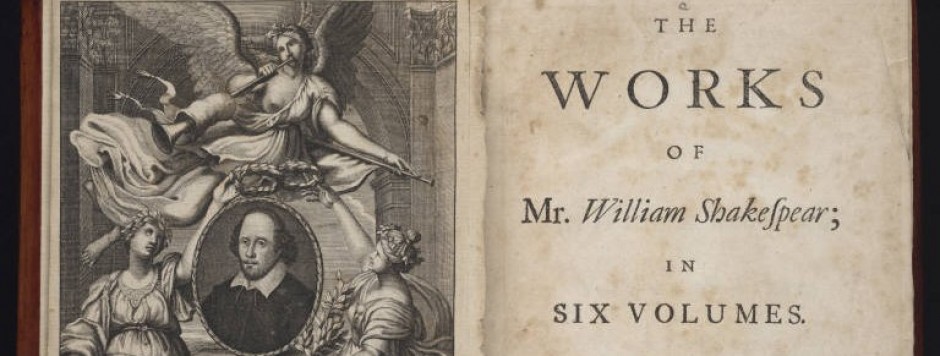

“The Preface of the Editor” by Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope includes a preface in volume one of his Shakespear where he outlines his intentions for the volumes to follow (Fig. 1). Pope demonstrates his desire to illuminate the beauty of the Shakespearean text, while also omitting parts of it that he deemed too ugly to have been Shakespeare. He does this by including a copious amount of footnotes that show his editorial process (see my page on footnotes for more information). Pope’s aim is to correct the errors that previous editions of Shakespeare had contained. Critic Adrian Johns writes that textual fixity was not always a “central characteristic of print. […] A century later, the first folio of Shakespeare boasted some six hundred different typefaces, along with non-uniform spelling and punctuation, erratic divisions and arrangement, mispaging, and irregular proofing. No two copies were identical” (282). Books, and in particular Shakespeare’s plays, were not always associated with the accuracy that the modern age attributes to them. Pope’s edition represents an attempt to collate Shakespeare’s work and publish the most accurate versions of them. However, Pope’s approach to editing Shakespeare’s works are criticized for being too subjective and taking too much liberty with the source material. Although that is certainly true, his preface is an interesting historical artifact regarding the beginnings of textual editing, while also raising important questions about the ethics regarding a creative approach to editing.

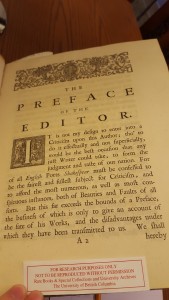

“Some account of the life, &c. of Mr. William Shakespear” by Nicholas Rowe 1709

Pope includes in the first volume of his 1725 edition of Shakespear a biographical piece written by the editor Nicholas Rowe in 1709, who published his edition of Shakespeare prior to Pope (Fig. 2). Rowe’s edition of Shakespeare was considered the first critical edition of Shakespeare ever published, one that attempted to modernize the spelling and to standardize the format for Shakespearean plays (which included the introduction of dramatis personae, and scene and act divisions in the text) (“Nicholas Rowe”). Pope formats his edition of the plays using the same methods that Rowe used. However, much of Rowe’s work has been criticized by scholars, since the accuracy of his biography of Shakespeare is dubious (“Nicholas Rowe”). Similar to biographies of Shakespeare that would follow Rowe’s, his version is full of hearsay and rumour. This problem regarding Shakespeare’s history will persist even during the modern age. The inclusion of this piece in Pope’s edition signifies an attempt by the editor to create a universal edition of Shakespeare’s place. Similar to introductions for modern books published by Penguin, Nicholas Rowe’s biography of Shakespeare is one of the first attempts to introduce the history of the author, and therefore emphasize his emerging place in literary canon.

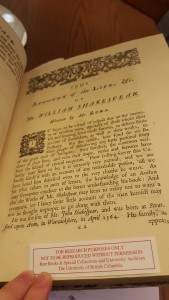

“Index” by Alexander Pope

Featured at the back of the sixth volume is an index that Pope includes to help the reader navigate his edition of Shakespear (Fig. 3). The index is notable because it also attempts to fulfill the role of a table of contents. Pope’s index categorizes sections of the book according to what he perceived were notable scenes or poetic devices. For example, if one wanted to look for significant similes or allusions regarding nature, the index section would list all the scenes across all six volumes of his edition that included poetic references to nature. By formatting his index in this way, Pope also reveals his own subjective approach to textual editing, since the index is categorized based on his subjective interpretation regarding the importance of certain Shakespearean words. Pope is imposing his own method of interpretation onto the reader who is trying to navigate his Shakespear.

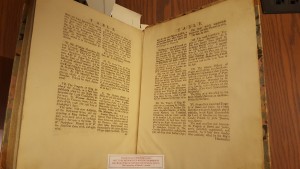

“Table” by Alexander Pope

Fig. 4: “A Table of the Several Editions of Shakespear’s Plays, made use of and compared in this Impression”

Also included in the back of Pope’s sixth volume is a table that lists all the previous editions of Shakespeare that Pope referred to when creating his own edition (Fig. 4). This section is interesting because it demonstrates an attempt by Pope to record his sources and back up his own additions to the text. The inclusion of this table reveals Pope’s editorial method, showing that his process was not based entirely on the subjective liberty that he has been criticized for. This table is also an interesting artifact regarding the evolution of textual criticism, since it offers a primitive bibliography that supports Pope’s additions and omissions. It aids in showing the interpretive process that is associated with editors of classical texts, while also demonstrating the book of the 18th century as a transitory object, one that is not regarded for the stability that modern audiences attribute to books.