Part 6: Literature Review: Entering a Conversation

Introduction

I have examined two different articles, that approach co-management in a slightly different light. I find it essential to examine the idea of co-management, as this looks at the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in respect of natural resources and how it is shared. While Houde examines “The Six Faces of Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Challenges and Opportunities for Canadian Co-Management Arrangements” (2007), I find that Tracy Campbell in “Co-management of Aboriginal Resources” (1996), introduces a more realistic view of co-management, highlighting the issues and dilemmas that this term encompasses.

Literature Review

Campbell states that co-management only goes back as far as ten years since 1996, while Houde says that the First Nations of Canada have been negotiating natural resources co-management arrangements over the last three decades (2007). Houde focuses primarily on part of the ‘traditional ecological knowledge’ (TEK) that the First Nations hold about the land and to come to agreements to the contentment of the First Nations people (ibid). Houde identifies six different “faces” of TEK which include factual observations, management systems, past and current land uses, ethics and values, culture and identity, cosmology, and specific challenges and opportunities that they pose on the co-management of natural resources.

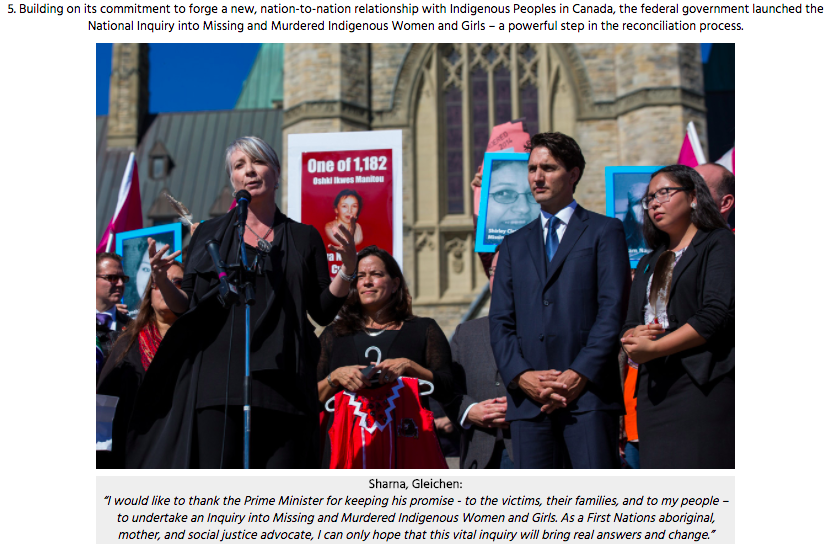

Houde states that bureaucratic resource management approaches have been criticized for driving ecological collapses and failing to improve people’s lives (2007). Thus, attention shifted to collaborative processes. Described as having “transformed and continue to transform the way in which resource management is undertaken in various Canadian provinces (Houde, 2007; Coates, 1992)”. Houde introduces the court action launched in the early 1970s by the Cree Nation of Québec, which led to the determination of the first Canadian modern treaty, the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement, which led to the emergence of co-management boards (2007).

Houde continues to highlight several “successful” decisions made such as the 1990 Sparrow decision, 1997 Delgamuukw decision, Haida vs BC and Taku River First Nation vs BC (2004) – which gave more leverage to the First Nations’ case which increased their role in strategic planning and natural resources policy making. What I find Houde primarily focuses on are these “successful” decisions made on co-management, without expanding in a more detailed fashion of the negative impacts that the First Nations had to put up with in order for these decisions to pass. Houde makes it sound like these co-management decisions are fine and dandy. Houde reiterates “co-management” as covering:

“From treaties to more informal arrangements, broadly refers to the sharing of power and responsibility between government and local resource users, this being achieved through various levels of integration of local and state level management systems” (2007; Notzke 1995:187).

While Campbell defines co-management as a consensus based, non adversarial method of negotiation that is successful from the sole perspective of the state and industry. Campbell finds it crucial to discuss land because they are tied to natural resources and the realistic issues of co-management, while Houde has constructed six faces to examine traditional ecological knowledge. Expanding on Campbell’s views, the amount of land and related natural resources that are in the control of aboriginal people is disputed by the federal and provincial government, resource industry representatives, and public groups. Historically, aboriginal people have been excluded from meaningful input (Campbell, 1996). These disputes over the right to the access and use of natural resources raise important questions pertaining to the relationship between First Nations people and the entirety of Canada (ibid). Disputes and disagreements have resulted in roadblocks, blockades, and other confrontational protests by the First Nations (ibid).

Campbell draws from a progressive co-management case in the North – the Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA), yet demonstrates how this can not be easily transferable to all cases. The IFA was accomplished through a 50% Inuvialuit representation, where each community created its own conservation and management plans which follow a main regional plan from 1988. It works in this case of the IFA but does not necessarily work for every community or dispute. The guarantee of hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering rights that are protected by the treaty can be seen as trapped within a vicious cycle of government policy, Campbell suggests. It is challenging to exercise federal treaty rights on provincial Crown land when neither of the government levels have any desire to step over the carefully delineated lines of constitutional jurisdiction.

For example, when the provincially managed boreal forest was being cut down, treaty rights were seen as a federal issue – and the development proceeded. Thus, Campbell sees the terminology of “co-management” as covering a broad range, that only implies equal rights (1996).

Houde, presents this figure below, and I will briefly explain each of the six faces (2007).

The first face represents factual observations, classifications, and the system dynamics. He calls this the most understood aspect of TEK, and describes this as specific observations that TEK holders are able to produce. This body of knowledge was first explored by non-aboriginal researchers through folk taxonomy studies – consisting of recognition, naming, and classification of discrete components of the environment (ibid).

The second face looks at resource management systems and how they are shaped by local environments. These include strategies for the sustainable use of local natural resources such as pest management, resource conservation, multiple cropping patterns, et cetera. I question here, whether these studies of management systems have been conducted largely by non-Indigenous people which leads me to think that this may hold a lot of bias.

The third face pertains to factual knowledge regarding past and current uses of the environment, focusing on the time dimension of TEK, and how this knowledge has been passed down through oral history (Houde, 2007; Neis et al. 1999, Usher 2000, Peters 2003). For example, this knowledge includes the location of medicinal plants and cultural and historical sites.

The fourth face looks at ethics and values. This component of TEK is the linkage between the belief system (the fifth face) and the organization of facts and actions. This includes values of correct attitudes, respect – between nonhuman animals, the environment, and humans.

The fifth face recognizes traditional ecological knowledge as a vector for cultural identity. Underlining the effect of language and images of the past in providing life to culture, Houde underlines the argument that the land is at the heart of aboriginal cultures and if the land were to disappear or transform extensively, cultures and peoples would also disappear (2007). Yet, what are people doing about this? This component acknowledges stories, values, and social relations.

Lastly, the sixth face is a ‘culturally based cosmology’ that is the foundation of the other faces and inseparable from them (Houde, 2007; Kuhn and Duerden 1996, Usher 2000). This section primarily perceives the assumptions and beliefs about how things work, and the way things are connected.

Conclusion

After Houde covers these six faces of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), I question the methods of implementation of each of these components. He goes on to introducing challenges to the first three faces being the control over the data generated by TEK and lack of confidence that non-Native people have in this data. Houde argues that the “lack of trust among people is an obstacle to co-management (2007, Olsson et al. 2004)”. He underlines the fundamental issue of the challenge for bureaucrats, who are used to specific ways of producing and monitoring information, to accept information produced by a largely different knowledge system (Houde, 2007). Houde concluded by saying that,

“To achieve this, flexible legal frameworks need to be put in place to allow for co-management arrangements to change and adapt over time as trust builds between partners.”

I believe this is a great statement in theory, but in practice, a lot harder said than done. Campbell questions whether ‘co-management’ may be the only practical way for the First Nations to have a dialogue with the government or industry. I believe this is an area that is still being examined, and requires an extensive amount of work in developing a positive role of the First Nations in co-management.

References

Campbell, T. (1996). Co-management of aboriginal resources. Information North, 22(1), 1-6.

Houde, N. (2007). The six faces of traditional ecological knowledge: challenges and opportunities for

Canadian co-management arrangements. Ecology and Society, 12(2), 34.