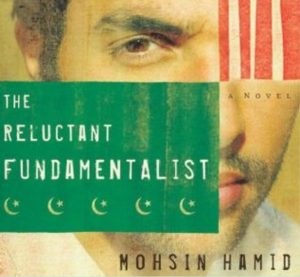

Mohsin Hamid’s psychological fiction The Reluctant Fundamentalist centers around a man named Changez and his experiences pre and post 9/11 as a Pakistani immigrant living in America. The novel, released in 2007, serves as a counter narrative to the master narrative that was circulating the U.S. during this time period, as stated by former U.S. President George W. Bush: “either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.” A clear example of the “false dilemma” fallacy, this narrative presented War on Terror as two-sided, and easily created to anti-Islamic sentiment that is still rampant in today’s America.

When discussing this in class, my mind immediately drew parallels to the narratives used during the Age of Colonialism and their impact on post-colonial narratives.

Colonial narratives centered around people of color as “inferior” or “degenerate” races, that needed help from the “superior” races (aka white people) as part of the “providential order of things for humanity,” (Renan). This idea of the “white man’s burden,” that black people REQUIRED the imposition of western civilization on their colonies, was used to justify an era of brutality, exploitation, and destruction of cultural identities. Similar to Bush’s decision to invade Iraq and the War on Terror, the spread of democracy was used as an excuse to invade other countries to gain and prove power during the Colonial Era.

The impacts of this narrative did not disappear in post-colonial society. Rather, they can be seen in the lasting view of white superiority and the institutional racism that persists in most European societies. Lasting colonial narratives point to the the inferiority of blacks as the cause of African disparity, when really, it is colonialism itself that is the cause of disparity. Africa is still seen as “less than” in most European societies; it is stereotyped as a dangerous, poor, uncivilized continent. In reality, this is only the master narrative– there are thousands of counter narratives of what Africa is and what it means to be African, pointing to its rich history and culture. Instead, it is reduced to a third-world continent of savages, largely because of the impact of this master narrative.

This lasting master colonial narrative and the racial and religious tensions it causes could even be argued as part of the cause of 9/11 itself and the still present anti-Islamic sentiment in the U.S.