Wrapping up our final weeks together in this term, our ASTU class has been reading the novel Disgrace written by J.M. Coetzee in 1999. Set in post-Apartheid South Africa, Disgrace tells the story of English professor, David Lurie; as he deals with the consequences of having an intimate relationship with one of his students, Melanie Isaacs. One of the major themes which arise throughout Disgrace is the concept of truth. In conjunction with our discussions regarding Disgrace, we also read an excerpt from the novel written by Antjie Krog, Country of My Skull. Country of My Skull is another South African novel which hits on the idea of truth in a crime. Similarly in both texts, there is a trial scene where the public is not content with the truth that has been revealed and would rather provoke a confession with an offer of remorse or reconciliation.

A pivotal scene in Disgrace which demonstrates the significance of truth occurs right in the middle of the novel (Chapter 6), where David is on trial for his crime. This scene has significance because it is the final moment in David’s life before he is officially “disgraced” from the Cape Technical University. In this moment, David accepts that he is “guilty of all that [he] is charged with” (49). As a response, many of David’s co-workers like Dr. Farodia Rassool demand to “register an objection” and Chairman Hakim question the sincerity of David’s confession (50). Throughout this meeting, David does not seem to reflect upon his actions nor apologetic. In his admittance to the crime, there is no emotion or guilt, just a plain confession with insincerity for what he has done to Melanie. This is further identified by Rassool when she says his confession has “no mention of the pain he has caused, […] the history of exploitation of which this is part”, when asked about the specificity of his crime (51). The behaviour exhibited by David demonstrates how he has told truth, but it does not evoke the same feeling of justice towards others.

In Country of My Skull, Krog approaches the idea of truth in a different manner, where she describes her own feelings. The text of Country of My Skull describes Desmond Tutu’s trial but through different genres like dialogue, journalistic and diary-like. Krog expresses her experience towards “truth” through her diary-like accounts but with the different genres, she is able to create a more rounded version of the truth. The dialogue resembles a testimonial rendition where the reader can have an objective view of exactly what was said. The journalistic description of the story may be the master-narrative which is popular among the public whereas Krog’s personal perspective offers a more raw and emotional counter-narrative. Krog’s thoughts can be read on page 50, where she says “the word “truth” makes [her] uncomfortable” to the extent where she hesitates and is “not used to using it” (50). By including moments like this in Country of My Skull, Krog effectively demonstrates how the trial has affected her on a personal level and gives the reader another perspective towards the word “truth”. In Krog’s passage, we can see how the perception around Tutu’s trial and idea of truth can be portrayed differently through three distinct narrative styles.

From reading these two novels, I also got to learn about South African history and the Apartheid. I am familiar with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Canada towards Indigenous communities but was unaware of the TRC in South Africa after the Apartheid. My understanding about the Apartheid was able to expand and develop through reading these literary works. With these novels and the looming end of the CAP program, I was able to reflect on the overarching theme of being a global citizen. Specifically, I was able to enrich an understanding of communities around the world; with how past events continue to affect the present day. Additionally, I was enlightened to see how every story has both a counter and master-narrative, where themes like “truth” may be misconstrued depending on the perspective.

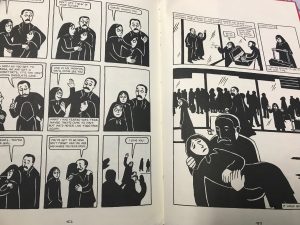

Another example is from pages 152-153, where we can see how all Marji and her parents are all dressed in black, which represents that there is a sense of somber amongst them and foreshadows to their separation. We can see throughout the graphic memoir, Satrapi uses black to represent sadness, suppression and violence. In many of the panels for war, riots and where Marji feels sad, black is predominant throughout the page. As for white, Satrapi uses white to show pure, heroic objects. For example, God, whom is sacred to her, and martyrs are dressed in white. The use of these contrasting colours allows Satrapi to communicate underlying feelings to the reader.

Another example is from pages 152-153, where we can see how all Marji and her parents are all dressed in black, which represents that there is a sense of somber amongst them and foreshadows to their separation. We can see throughout the graphic memoir, Satrapi uses black to represent sadness, suppression and violence. In many of the panels for war, riots and where Marji feels sad, black is predominant throughout the page. As for white, Satrapi uses white to show pure, heroic objects. For example, God, whom is sacred to her, and martyrs are dressed in white. The use of these contrasting colours allows Satrapi to communicate underlying feelings to the reader.