Hello again ASTU!

We have almost wrapped up our first year at UBC and this will be the last blog post of this year!

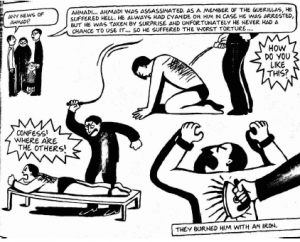

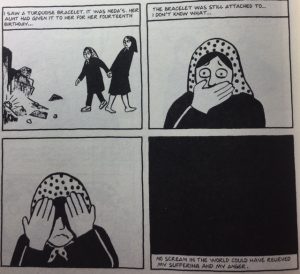

As part of the last readings we are doing for this semester in ASTU, Disgrace by J. M. Coetzee was a very different and difficult to digest piece of reading, and there were many layers and themes to unpack. As readers, mature topics and disturbing content are a commonality in literature. Earlier in the semester, we dove into Maus, which its plotline surrounded the events of the Holocaust, and Mrs. Dalloway, that handled sensitive issues such as PTSD and suicide. However, the air of taboo surrounding sex is still prevalent in common discussion and often seen as an inappropriate subject to approach. Although there were sexual elements and themes in previous literature we have examined, none had been as explicit, as the themes in Disgrace can be seen as directly unsettling to many people, even though as readers, we have almost become desensitized to these topics in literature.

We are introduced to the main character, David Lurie, a professor at Cape Technical University. A picture is painted for Lurie as an older man, Coetzee gives an almost unprompted introduction to Lurie, as the topic of sex is put on the forefront of the main character. Into the first page, Lurie’s character is established well enough to understand his relationship towards sex, and by extent, towards women. He has “solved the problem of sex rather well”, by purchasing from a sex worker named Soraya (Coetzee 1). That in itself can be seen as ‘disgraceful’ and a taboo thing to do, although it may seem like a common ordeal. Men like Lurie are often seen as characters that are naturally dominant and traditionally natural for a woman to give way to his needs.

Almost each seemingly questionable act that Lurie commits himself to do, he allows himself to find excuses or justifications for them, even if it seems that he casts doubts. This can be first seen as Lurie was reflecting on his relationship with Soraya, and “Technically he is old enough to be her father; but then, technically, one can be a father at twelve.” (2) He then decides to court another woman, a secretary in his work field. He found her distasteful afterwards and promptly cuts off contact. To further this stream of problematic acts, Lurie initiates an affair with one of his own students named Melanie. He rationalizes and normalizes his behaviour as he courts numerous of women, ultimately finding sex the object of his admiration or interest.

To point out the obvious, it is commonly seen as inappropriate to instigate intimate relationships between someone in a position of power and an individual under their tutelage or otherwise working relationship, as it can be a lead to abuse of power and that society has largely deemed it immoral and inappropriate. In other words, also taboo and in some cases against the law and this applies to everyone, regardless of gender. In Lurie’s scenario, it can be interpreted that this affair was a coerced and almost forced relationship, as Melanie is often finding ways to avoid prolonged interactions. She actively tries to find escape routes, such as a flatmate in the house or busy for rehearsals. Despite this, Lurie had forcibly made his way into her life, going as far as recording her personal information through her student records, not unlike how he took Soraya’s information without consent. He continues to push those boundaries by taking sex from Melanie, never truly forcing, but never welcomed either, and consent is dubious.

There is also a recurring theme of double standards in terms of gender expectations, especially in Lurie’s perspective. This is obviously seen in his conversations and musings with the women he interacts with; Melanie when he insists that a woman’s beauty needs to be shared and with his daughter Lucy, when he finds her an undesirable character because she refuses men and does not meet his standards on beauty.

David Lurie had been immediately understood to be an ‘unlikeable’ character. Readers are often able to understand that his behaviour is generally unacceptable in our society and should be condemned. Although the university publicly shamed his actions and set disciplinary actions, Lurie was removed from his position of teaching and sent out, he was not pressed with charges or subject to definite punishments. He does not take fault in his actions and believes that there is nothing wrong with his character in regards to the scandal, besides that it is society’s judgment that condemned him. However, Coetzee did not feed this idea directly through the text, and we are left to infer and create this opinion.

By depicting David Laurie as a ‘disgraced’ Coetzee is able to describe the unfathomable situation that women are often subjected to. Readers are able to look at what occurs on a daily basis, not only in South Africa but everywhere in the world. New studies and surveys have found that approximately 80% of women have been victims of sexual assault or harassment, or assault in their lifetime. While statistics and sheer facts may be unable to bring to light these issues to desensitized individuals, Coetzee’s Disgrace can be seen as a method to sensitize the double standard and issues to sex and manipulation of women. It is in fact still a disturbing topic that should be scrutinized and criticized.

Thank you for reading!