(A blog post by one of our research assistants, Amber Leenders.)

In the course of reading about manuscripts and their importance in late antique Gaul, I recently came across a curious reference to the seventh-century figure of St. Eloi. According to his hagiographer, the bishop Audoin, Eloi was in possession of a “revolving bookcase.” The phrase that Audoin uses is libros in giro per axem, translated as something like “a great many sacred books arranged in a circle turning on an axis.” He describes how the saint, deep in his routines of prayer and devotion, plucked books out of the revolving structure and flitted from one to the other like “a very wise bee.” St. Eloi’s shelf probably turned on a central, vertical axis like this one.

While it’s fantastic to think about such a feature in the saint’s personal study, I had to wonder – what was the norm for book storage at this time? The revolving bookcase does not reappear until centuries later, and judging from the lack of vocabulary to describe it in Latin, it had not been popular before this point either.

As Rouse and Rouse point out in their article about St. Eloi’s books, the appearance of such a bookcase shows acceptance of the codex form over the earlier papyrus roll. Before the transition to the codex, texts would have usually been written on papyrus scrolls. These were rolled up and stored lying flat on shelves, with an identification tag at the end so it was easy to identify the manuscript. The word for this summarizing tag in Greek is sillybos—the origin of our modern word “syllabus.”

Codices could have been stored on shelves too, although they were not necessarily stood on end like modern library books. The shape of a manuscript’s binding and the location of its title can provide clues as to how it was stored. A good example is the binding of Byzantine books; the end band (the binding of the spine of the book) would often extend past the length of the pages, making it unstable in this position. (See this video for more information.)

Instead of standing such codices upright on shelves, it is more likely that they were stored in chests, such as the one shown in the illuminated manuscript below. This would have been a good way to protect the books and give them a storage space to lie flat:

Portrait of St Matthew from the Askew Gospel Book. London, British Library, Add MS 5111, f 12r. Eastern Mediterranean, 12th century.

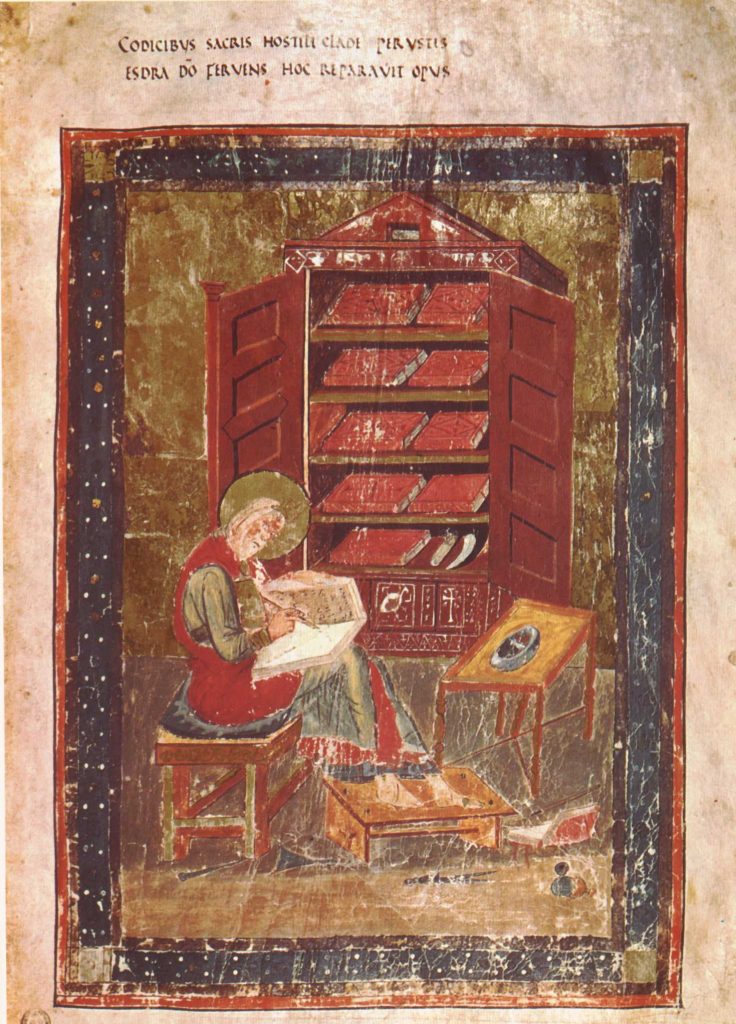

In late antique Gaul, books were considered an essential feature in monasteries, and might have accumulated in scriptoria where monks could read and work as scribes. An illustration from the Codex Amiatinus shows a possible method of monastic book storage: sturdy wooden cupboards, with books lying flat on the shelves.

Portrait of Ezra from the Codex Amiatinus. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Amiat. 1, f. 5r

Whether shelf, cubicle, chest, or a saintly rotating bookcase, the storage methods for books can tell us interesting things about how manuscripts were made, stored, and accessed.

Sources:

Marzo, Flavio. ‘Byzantine Bookbindings’. The British Library Greek Manuscripts website, https://www.bl.uk/greek-manuscripts/videos/flavio-marzo-on-byzantine-book-bindings

Nicholls, Matthew. ‘Ancient Libraries’. The British Library Greek Manuscripts website, https://www.bl.uk/greek-manuscripts/articles/ancient-libraries.

Parpulov, Georgi. ‘Byzantine Libraries’. The British Library Greek Manuscripts website, https://www.bl.uk/greek-manuscripts/articles/byzantine-libraries.

Rouse, Mary A., and Richard H. Rouse. ‘Eloi’s Books and Their Bookcase’. Manuscripta 55 (2011), pp. 170–92. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.MSS.1.102557

Amber Leenders is an MA student in Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology at UBC and a Research Assistant on the Ancient Books Project.