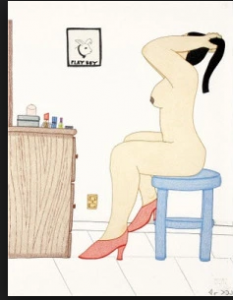

Annie Pootoogook’s Women at her Mirror (Playboy pose)

“Inuit artists have depicted their early interactions with settlers in speculative ways using futuristic imaginative concepts: a future imagery in the present”

-anishinaabe-nehiyaw writer Lindsay Nixon from her piece Visual Cultures of Indigenous Futurisms

————————————————————————————–

Annie Pootoogook’s Drink and Draw 2012

————————————————————————————–

“Technology is not divorced from or forced upon land but develops in relation to lands and the many beings land supports”

Diné writer Lou Catherine Cornum Diné from “The Space NDN’s Star Map”

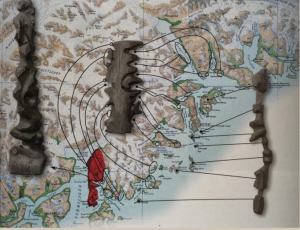

“In Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland), the Inuit people are known for carving portable maps out of driftwood to be used while navigating coastal waters. These pieces, which are small enough to be carried in a mitten, represent coastlines in a continuous line, up one side of the wood and down the other. The maps are compact, buoyant, and can be read in the dark” https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/2016/04/12/inuit-cartography/

————————————————————————————-

Kananginak Pootoogook’s An inukshuk 1997

Kananginak Pootoogook’s An inukshuk 1997

————————————————————————————-

Colonialism loves to plant flags, and yell “mine” like a bunch of spoiled toddlers. The race to claim ‘sovereignty’ in space, extended from a sense of colonial ownership and ‘discovery’ of spaces on earth. In the dominant western construct, the race to ‘claim’ the arctic was not much different then their vision of putting a flag on the surface of the moon. To them it was all one and the same terra nullius.

Inuit futurism, an extension of Indigenous futurism, works to push back against the white man planting flags, and reasserts the ongoing presence of Inuit peoples and land. In Inuit futurism the Inuit experience is illustrated through film, art, music fashion, food sovereingty, and a discourse about a changing climate, as Inuit peoples and their cosmologies, unique histories, language and culture present, as anishinaabe-nehiyaw writer Lindsay Nixon articulates, “futuristic imaginative concepts in the present” (Nixon 2016).

————————————————————————————–

I’ve been thinking a lot about Annie Pootoogook and her death this past September 19th.

The more I explored her work, the media surrounding her death, the racist comments made by the police officer involved in her case, the more I further realized how fucking violent mainstream media’s perpetuation of colonialism through perpetuation of systemic racism actually is.

————————————————————————————–

I first began this blog research by trying to map out Annie”s family, and other matriarchal Inuit artists from her community of Kinngait

The first wave :

Pisteolak Ashoona, Kenojak Ashevak, Jessie Oonark, amongst others,

The second wave: Napachie Pootoogook, Janet Kigusiug,

The third wave:

Suvinai Ashoona, Siasie Kennally, Annie Pootoogook ( granddaughter of Pisteolak Ashoona, and daughter of Napachie Pootoogook).

*Annie Pootoogook’s Pitseolak Drawign with Two Girls on the Bed’ 2006. Depicting Annie, her mother Napachie Pootoogook and grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona.

————————————————————————————-

I then began researching events that corresponded with the year pieces of Annie’s art were made such as

Annie Pootoogooks’s Sobey Awards 2006.

I then somehow fell down deep rabbit holes of western climate change rhetoric, CNN articles touting scientific vernacular of climate change as a new or emerging ‘discovery’, working to silence, dismiss and oppress Inuit knowledge, while simultaneously reinforcing a colonial construct of ‘the other’, resulting in countless colonial legislations, including blaming this ‘other’ for species extinction through over use, and banning Inuit hunting and fishing practices. It was there I found my inspiration for my proposed Timetraveller™ episode treatment.

I became a little overcome with the main stream use of language surrounding climate change. I read the first chapter, of Tahltan writer Candis Callsion’s book “How Climate Change Comes to matter: The Communal Life of Facts” ,The Inuit Gift , in which she addresses American main stream media surrounding climate change. And the danger of main stream media’s language surrounding climate change through the continual attempt to erase Inuit culture, cosmology, history, experience, connection to the land and food sovereingty through scientific vernacular. Callison spoke to the way mainstream language surrounding climate change “comes with its own set of baggage or rules, grammars, exceptions, and associations, confrontations with history, institutions, and power relations” (Callison 2014). She goes on to say “The absurdity of trying to sum up a lifetime of discrete observations layered on oral histories and community consensus about witnessing environmental change in one term is striking…climate change is the continued process of foreclosure on hope, begun by encounters with colonialism and the enduring structures it put in place via education and mechanisms (or lack thereof in previous eras) for governance, communication, accountability, and self-determination. The environment is also an extension of and constituent to culture” ( Callison 2014).

Callison also speaks at length with Sila Watt Coutier who sits on the Inuit Circumpolar Council, who speaks to the ways Inuit experience of a changing climate is inextricably linked to Inuit culture and cosmology.

“it’s all connected. You have to look at the larger picture of how our hunting culture is not just about going out and killing animals; it is about pre paring our young people for everything, challenges and opportunities. And it is because of that disconnect between our children being prepared with the character building that a hunting culture gives and the institution separating that completely in terms of how to be taught, how to be patient, to be bold under pressure, to withstand stress, how to be courageous, how not to be impulsive, how to have sound judgment and wisdom. That is all the hunting culture that gives that”(Callison 2014).

From Zacharis Kanuk’s film “Inuit Knowledge and Climate Change”

I found this work relevant for my blog post as it highlighted the colonial violence and systematic racism embedded in main stream media’s reporting on the perceived Inuit experience. And something I wanted to address in a proposed episode of Timetraveller™. I started looking at suicide rates in Inuit communities…higher then anywhere else in the world, and federal ‘apologies’ for brutal forced relocations all in the horrendous name of ‘arctic sovereignty’, simultaneously romanticizing and histrorisizing Inuit culture. I then needed a break so I played more Never Alone than I ever have, and watched all of Inuit film maker Zacharis Kanuk’s films.

I don’t know what I can do with this research, but throughout all of it, I kept coming back to Annie Pootoogook. Her work is an incredibly powerful illustration of Inuit futurism, in an almost haunting way. It stays with you. It inspired me to learn some Inuit history. She highlights the connections of Inuit cosmology, language, experience, and reality, as well as bringing attention to the dominant western rhetoric continually attempting to claim this land and these peoples.

Annie’s work speaks to the residues of a colonial race to arctic ‘sovereignty’, and the ongoing colonialism in her community. Annie’s work also portrayed Inuit resistance, and resilience by including profound imagery of an imagined Inuit future into present and everyday Inuit experiences. She commented on, and challenged the dominant colonial construct that has seen, and often time still sees Inuit culture as disposable, and a guinea pig to continually conduct experiments on… whether that is through forced relocations in the 1950’s or the continued scientific research on Inuit animals through tagging and micro chipping.

Throughout all of this, I became a little overcome with the language around climate change as presented in mainstream media and just how violent that was. There is a distinct voice of Inuit life and culture in Annie’s pieces but also a prolific comment and push back against colonialism, imagined through a lens of Inuit futurism.

.

Annie Pootoogook date unkown

————————————————————————————–

Annie Pootoogook Cape Dorset Freezer 2006

————————————————————————————–

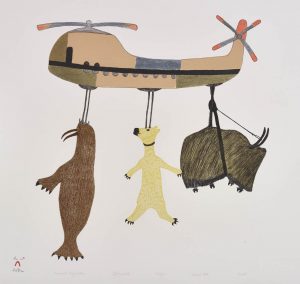

Annie as well as other Inuit artists of her time assert their continued resistance through their continued use of technology… a technology that is inextricably connected to their culture. As anishinaabe-nehiyaw writer Lindsay Nixon says in her article Visual Cultures and Indigenous Futurisms,

“Inuit artists have depicted their early interactions with settlers in speculative ways using futuristic imaginative concepts: a future imagery in the present. One jarring example is Ovilu Tunnillie’s green stone carving This Has Touched My Life (1991-92)

, a representation of the artist’s experience of being removed from her home and taken to an infirmary in the South, her first time away from her home in the North. The nurses who are escorting Tunnillie are wearing veiled hats but, in Tunnillie’s depiction, the hats look like space helmets.

, a representation of the artist’s experience of being removed from her home and taken to an infirmary in the South, her first time away from her home in the North. The nurses who are escorting Tunnillie are wearing veiled hats but, in Tunnillie’s depiction, the hats look like space helmets.

Pudlo Pudlat is often revered for being the first Inuk to feature Western technology in his work; his lithograph Aeroplane (1976) even appeared on a Canadian postage stamp.The irony, of course, is that the Baffin Island Inuk artist’s usage of speculative visualities actually critically engages with destructive colonial technologies rather than condoning them. In Pudlat’s lithograph Imposed Migration (1986), he depicts an otherworldly flying object: a UFO, if you will. The UFO is cabled to a variety of northern animals: a walrus, a bear, and a buffalo, and is lifting them off the ground, transplanting them to new territories. The absurdity is transparent. To remove kin from their home territories is to separate them from their context, to remove their very essence and connection to the land. Here Pudlat is openly denouncing the colonial project of forced removal and migration inflicted on Inuit communities in the North.” (Nixon 2016).

Pudlo Pudlat Imposed Migration 1986

————————————————————————————–

I had troubles connecting with Second Life on multiple occasions but this is what I had in mind.

Based off my research of Inuit futurism in the first section of this blog post I wanted to propose an episode of Skawennati’s Timetraveller™ in which Karahkwenhawi and Hunter’s future daughter is the one doing the travelling. She would be time travelling to 2050 and this leanne Betasamosake Simpson song would play as the episode starts. Please play the second song of this playlist, “Under Your Always Light (Teeqwa Remix)”.

The episode would start with their daughter studying in her room. We would see Karahkwenhawi holding a pair of time traveller glasses, she would go to her daughter’s room and knock on the door, and come in and sit on her daughters bed, and gift the glasses. Daughter would get a notification on her computer cordially inviting her to the 30th annual Inuit Youth Circumpolar conference in Katzebue Alaska. I wanted to include this particular mix (the second track of the list of seven tracks Teeqwa Mix) of leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s song ‘Under Your light’ as I feel it is beautifully feminine, maternal, and the beat plays with timing and Leanne’s voice, creating a sense of excitement, urgency and speed, perfectly fitting for an episode in which Karahkwenhawi’s daughter’s is getting ready to time travel for the first time. We see daughter put a photo of her parents as well as some research materials in a back pack as the song builds. She would be seen hugging her parents, and once she had her glasses on, we first see her parents holding eachother in a long embrace, nervous to see their child timetravlling.

She would travel to Kotzebue, Alaska, in Iñupiat territory. She would be in Intelligent agent mode able to interact with others at the conference and affect the outcome of the episode. As the song fades out she looks around at the others gathered in a large conference room, walls hung with Annie Pootoogook drawings. Many Indigenous youth are gathered.

as Erica Violet Lee’s articulates in her article Reconciling the Apocalypse ,”Métis elder Maria Campbell told us the job of writers and artists is to be mirrors for the people; that “we build what could’ve been, what should’ve been.” In knowing the histories of our relations and of this land, we find the knowledge to recreate all that our worlds would’ve been if not for the interruption of colonization”

“As settler colonial governments continue to demand more and more from the Earth, indigenous peoples seek the sovereign space and freedom to heal from these apocalyptic processes”

-LOU CATHERINE CORNUM “The Space NDN’s Star Map”

2050, Inuit knowledge is now fully recognized world wide, and governs all resources, and energy projects in collaboration with other Indigenous communities and Nations.

As changes within Inuit climate are so felt and seen in their communities in such a critical and unique ways, they have been nominated as witnesses and protectors, elected by Indigenous groups Nation wide to advise and report on the climate and extend guidance for resources. The Inuit Youth are the governing body and have invited Karahkwenhawi and Hunter’s daughter to participate in their annual meeting, this year held in Kotzebue.

This Inuit youth coalition would have been governing and leading resource related projects and monitoring their changing climate for the past 30 years. After Indigenous led resistance took back North Dakota in 2016 First Nation, Inuit and Metis communities across North America allied in establishing entirely new guidelines for energy use, resources, education, land claims, and food sovereingty.

Hunter’s daughter would meet someone at the conference, a young man from the community who speaks Iñupiaq, which would be the main language used and seen in this episode. We would see the two engaging in meaningful conversations at the conference as well as interacting with Annie’s art hung on the walls of the conference hall.

Resources:

1. Callison, C. (2014). How climate change comes to matter: The communal life of facts. Durham: Duke University Press

2. Qapirangajuq: Inuit knowledge and climate change. Kunuk, Z., Mauro, I. and Igloolik Isuma Productions (Directors). (2010).[Video/DVD] Toronto, ON: V Tape

3. TimeTraveller™. (n.d.). Retrieved November 28, 2016, from http://www.timetravellertm.com/episodes/episode06.html

4. The Space NDN’s Star Map.(2015). Retrieved November 28, 2016, from http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/the-space-ndns-star-map/

5. G. (2016). Visual Cultures of Indigenous Futurisms. Retrieved November 28, 2016, from http://gutsmagazine.ca/visual-cultures/

7. RPM Records: Leanne Betasamosake Simpson – Under Your Always Light. (n.d.). Retrieved November 28, 2016, from https://soundcloud.com/rpmfm/sets/leanne-betasamosake-simpson-under-your-always-light-single

David Gaertner

November 30, 2016 — 10:18 pm

This is a beautifully rendered and thoughtful piece, Annie. I very much enjoyed reading it. I am particularly grateful for the ways in which you are able to weave Pootoogook’s work into your definition of Indigenous Futurism. You’ve given me a lot to think about. Inuit Futurism itself is something that has not received a lot of critical attention and you set up some important foundations for us to consider this branch of the work. Great work!