Found in an alley north of Water street, behind popular shops and restaurants in Gastown the historic heart of Vancouver. Not far from here is the heart of the Downtown Eastside, home of “worst drug problem in Canada,” (Macdonald, 2009) where drug related deaths are 7 times the provincial average (Bruxton et.all, 2010).

Found in an alley north of Water street, behind popular shops and restaurants in Gastown the historic heart of Vancouver. Not far from here is the heart of the Downtown Eastside, home of “worst drug problem in Canada,” (Macdonald, 2009) where drug related deaths are 7 times the provincial average (Bruxton et.all, 2010).

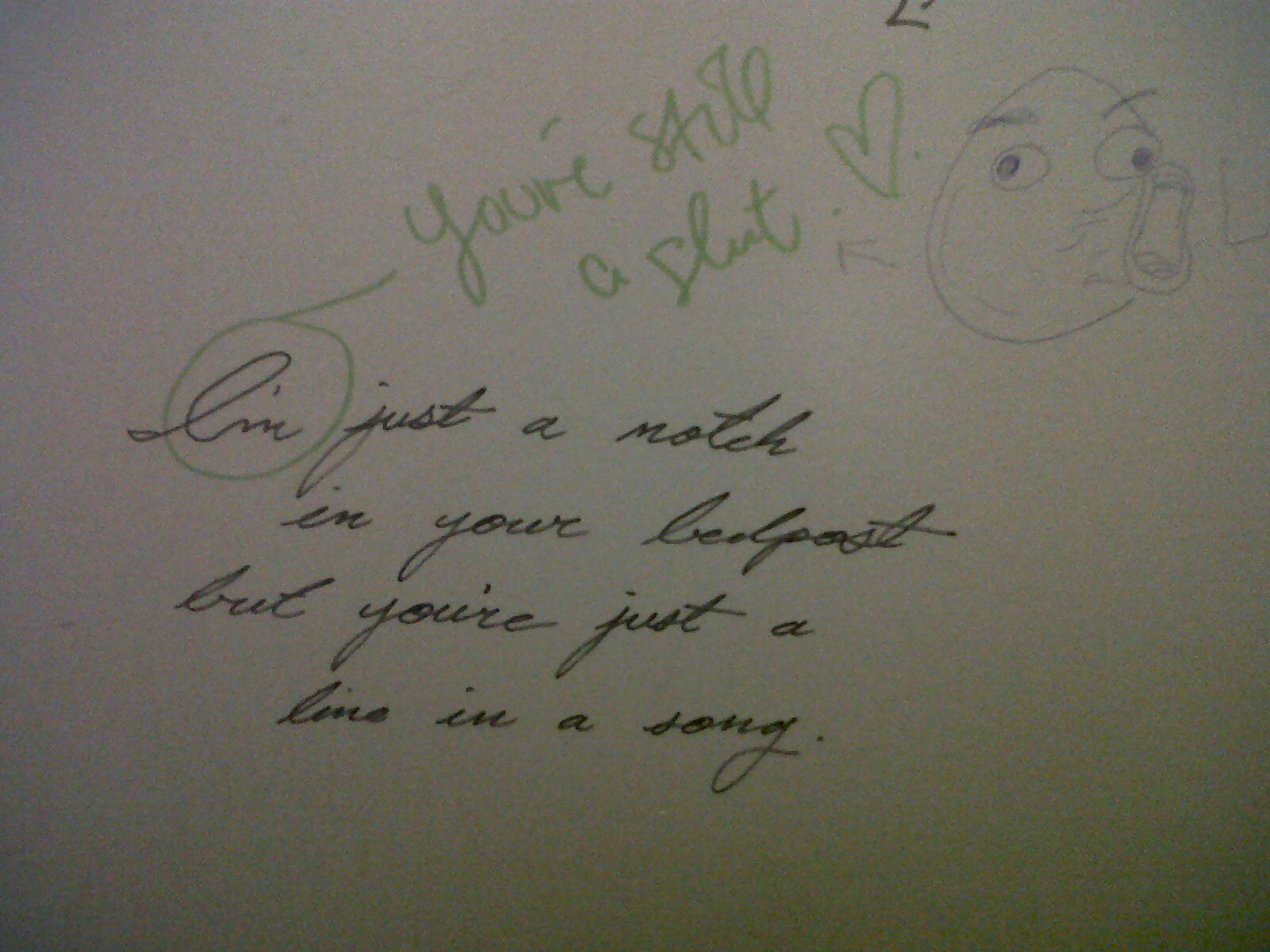

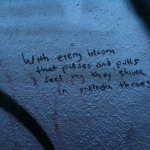

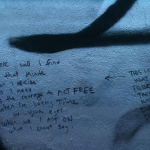

Within the larger tag-bomb, a silver human-height signature that stretches several paces of wall, are a series of comments. These comments are written with marker, and look a lot like what you would find scrawled in a library cubby. What they represent is dialogue, materializing one of the key social issues of Vancouver’s urban space.

Brighenti describes walls as “part of the unquestioned here-and-now of a given urban environment,” tactical placement of visuals focus public attention (Brighenti, 2010). This wall is behind a row of chic furniture and tourist shops, a stark symbolic contrast to a localized homeless population. I didn’t have to travel far, but an effort was made- needed to be made, in order to find it.

Graffiti is not particularly rampant in this city. Homelessness is. Both are a visible affront to public space, and generate similar, seemingly unending debates. Regardless of aesthetic appeal, this particular graffiti acts a medium on “the street,” as it materializes a dialogue of “the street.” This is not to say that anyone intended it to be such, authorial intent is impossible to determine in this context, thus it is read entirely as-is, in the here-and-now. What materializes is a visual conversation happening at the backstage of Vancouver’s most historic space: a powerful symbol for the affliction at the tip of the public tongue.

Bibliography.

Buxton, Jane A., Azar Mehrabadi, Emma Preston, Andrew Tu, and The Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (CCENDU) Vancouver-Site Committee.

2010 Local Drug Use Epidemiology: Lessons Learned and Implications for Broader Comparisons. Contemporary Drug Problems 36 (Fall/Winter):447-458.

Brighenti, Andrea Mubi.

2010 At the Wall: Graffiti Writers, Urban Territoriality and the Public Domain. Space and Culture, 13(3): 315-332.

Macdonald, Nancy.

2009 Vancouver’s Drug Woes Escalate. Maclean’s, December 28, 2009: 25