Graffiti is an outright, spontaneous expression of your inner feelings that are anonymously displayed to a public audience. It seems as though the public recognition of an expression through graffiti helps individuals cope with their problems better. In Israel, following the assassination of the Israeli prime minister, the Israeli teenagers found it easier to mourn his death through the use of symbols, with graffiti being the medium outlet (Luzzatto and Jacobson 2001:363). Therefore, can graffiti act as a coping strategy to allow a person to release their anguish and emotions in an anonymous, yet public way? I think that graffiti effectively provides this outlet because it creates anonymity. It also allows for the public recognition of a person’s message.

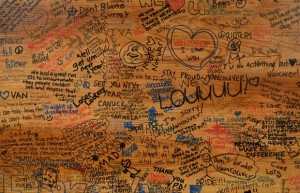

Despite the amount of damage caused by the Stanley Cup rioters, everyday Vancouverites emerged from the dust and debris the next morning to clean up the downtown area. The Bay windows were extensively damaged, and as a result, they were boarded up with wooden planks. When the first sign of apology was placed on one of the planks, this created an outburst of emotional messages from various people who took to the wall to express their feelings. By expressing their individual messages on the wall, it allowed everyone to cope with the riot better. I think that this allowed people to overcome the emotional shock of the riot by using graffiti to publicly express their feelings. This “graffiti wall” is the physical representation of the coping strategy employed by the society.

Reference

Luzzatto, D., and Jacobson, Y.

2001 Youth Graffiti as an Existential Coping Device: The Case of Rabin’s Assassination Journal of Youth Studies 4(3):351-365.