Graffiti on Granville by Kimi Yoshino

Graffiti or ‘street art’ has come a long way from being marginalized as the ‘graffiti problem’ in the ‘70s – ‘80s, to recently, where it has been elevated to the status of ‘normalized art.’ Behind this phenomenon is the ascension of corporate power/culture and restructuring of networks in the public and private sectors. Street art has been gaining momentum as it is seen by the mainstream media as the manifestation of the ‘creative class,’ expressing their identity in juxtaposition to their environment (whether this be in regards to capitalism or anti-immigration policies) in the form of sanctioned art. In regards to this specific piece that I discovered on my way to Granville Island in Vancouver, because it resembles First Nations’ artwork its significance may lie in the issues of regaining the sense of ‘belonging’ in the contested areas of Vancouver. As described by Banet-Weiser, graffiti often reflects “subcultural energy and artistry” (Banet-Weiser 2011), celebrating the urban cities’ grit and character. Its value lies between the real, material world (to the residents and workers), and an “abstract space for capital investment” (ibid). Artists operate between these binaries, as this art becomes a way for them to craft individual identity by gaining self-agency and distinguishing himself/herself from the collective, to establish entrepreneurialism. This, in turn, contributes to the tourist revenues and the city’s reputation. As this graffiti was situated at the entrance of Granville Island (a hot tourist destination), this could relate to the corporate elites’ attempt to converge the economic with the cultural sphere, creating a new discourse –a trend- that paves way for more innovative concepts to discuss what it means to be ‘creative,’ or even ‘authentic’ today.

Graffiti or ‘street art’ has come a long way from being marginalized as the ‘graffiti problem’ in the ‘70s – ‘80s, to recently, where it has been elevated to the status of ‘normalized art.’ Behind this phenomenon is the ascension of corporate power/culture and restructuring of networks in the public and private sectors. Street art has been gaining momentum as it is seen by the mainstream media as the manifestation of the ‘creative class,’ expressing their identity in juxtaposition to their environment (whether this be in regards to capitalism or anti-immigration policies) in the form of sanctioned art. In regards to this specific piece that I discovered on my way to Granville Island in Vancouver, because it resembles First Nations’ artwork its significance may lie in the issues of regaining the sense of ‘belonging’ in the contested areas of Vancouver. As described by Banet-Weiser, graffiti often reflects “subcultural energy and artistry” (Banet-Weiser 2011), celebrating the urban cities’ grit and character. Its value lies between the real, material world (to the residents and workers), and an “abstract space for capital investment” (ibid). Artists operate between these binaries, as this art becomes a way for them to craft individual identity by gaining self-agency and distinguishing himself/herself from the collective, to establish entrepreneurialism. This, in turn, contributes to the tourist revenues and the city’s reputation. As this graffiti was situated at the entrance of Granville Island (a hot tourist destination), this could relate to the corporate elites’ attempt to converge the economic with the cultural sphere, creating a new discourse –a trend- that paves way for more innovative concepts to discuss what it means to be ‘creative,’ or even ‘authentic’ today.

References:

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2011). CONVERGENCE ON THE STREET. Cultural Studies, 25(4/5), 641-658

- Kramer, R. (2010). Moral Panics and Urban Growth Machines: Official Reactions to Graffiti in New York City, 1990–2005. Qualitative Sociology, 33(3), 297-311.

- Taylor, M. (2012). Addicted to the Risk, Recognition and Respect that the Graffiti Lifestyle Provides: Towards an Understanding of the Reasons for Graffiti Engagement. International Journal Of Mental Health & Addiction, 10(1), 54-68.

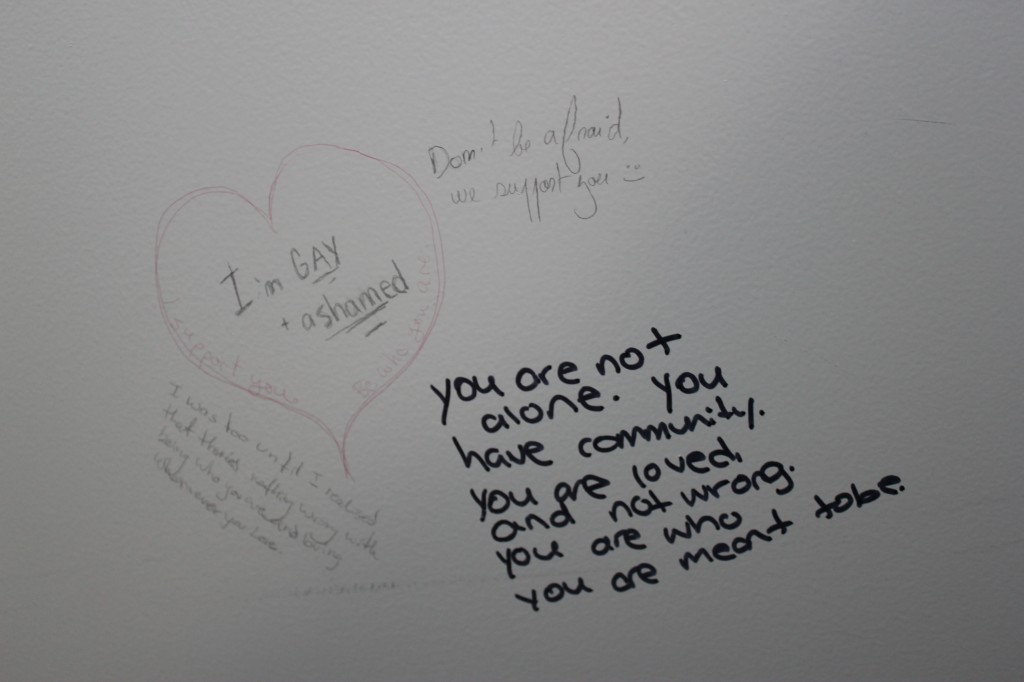

This photograph of “latrinalia” (Cole 1991:403) was taken in a women’s washroom stall in Buchanan. The privacy that this location provides has contributed to the formation of a community who, although strangers, communicate via the stall door. The privacy of the stall allows for an increased anonymity, and due to the gender-specific location, women are “able to share interests and experiences they may not generally share with men” (Cole 1991:403). Entitled the “SEX DOOR,” this particular graffiti contains a frank commentary about sex that might be considered inappropriate if verbalized. One comment reads, “Nothing wrong with anal.” Another asks, “Does sex actually feel good? Because fingering doesn’t feel like anything. Is that normal?”

This photograph of “latrinalia” (Cole 1991:403) was taken in a women’s washroom stall in Buchanan. The privacy that this location provides has contributed to the formation of a community who, although strangers, communicate via the stall door. The privacy of the stall allows for an increased anonymity, and due to the gender-specific location, women are “able to share interests and experiences they may not generally share with men” (Cole 1991:403). Entitled the “SEX DOOR,” this particular graffiti contains a frank commentary about sex that might be considered inappropriate if verbalized. One comment reads, “Nothing wrong with anal.” Another asks, “Does sex actually feel good? Because fingering doesn’t feel like anything. Is that normal?”