With the rise of social media in the last decade, K-pop has made its way to the international realm. Oh and Park’s article argues that social media outlets such as YouTube are pivotal to K-pop’s global expansion; however, artists and music producers have to “find other sources of revenues streams” since music consumers, specifically K-pop fans, are not required to pay to access music content from their favourite soloists or groups on YouTube (Oh and Park 2012: 368-372). As long as the digital gadget is accessible to the Internet, fans can stream their favourite music videos via the YouTube app. Therefore, social media platforms may serve as a mode of promotion for the musical content of the artists, but it is not enough to financially sustain soloists or groups in South Korea.

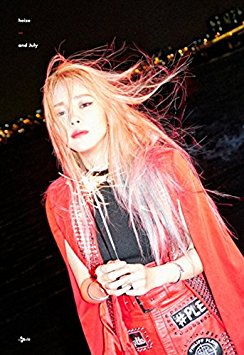

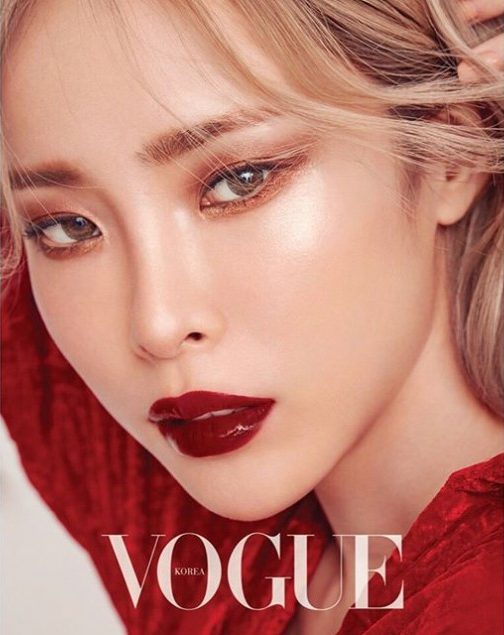

In relation, Oh and Park point out that the decreasing sales CDs and DVDs is due to the “rampant unchecked piracy”. K-pop fans do not need to buy the entire album because virtual music shops like iTunes make it possible for consumers to purchase the songs they only like, which help producers combat piracy (Oh and Park 2012: 372-374). Despite profit from digital singles or albums, it does not necessarily make  an artist financially stable. According to a news report by JTBC Newsroom from August 21st, 2017, an artist makes 0.42 won, which is about $0.00042 per streaming. In a given example, Heize had only earned 2.7 million won, about $2,700, in spite of topping every chart ranking in July 2017. The news provides a breakdown of the profit: 40% for the distribution; 44% for the production; 10% for composition/writing/editing; and the remaining 6% goes to the artist. This reveals that the artist themselves earn the least in streaming, which has led to some artists to participate in song writing.

an artist financially stable. According to a news report by JTBC Newsroom from August 21st, 2017, an artist makes 0.42 won, which is about $0.00042 per streaming. In a given example, Heize had only earned 2.7 million won, about $2,700, in spite of topping every chart ranking in July 2017. The news provides a breakdown of the profit: 40% for the distribution; 44% for the production; 10% for composition/writing/editing; and the remaining 6% goes to the artist. This reveals that the artist themselves earn the least in streaming, which has led to some artists to participate in song writing.

On a brighter note, Oh and Park note that K-pop artists and their entertainment companies gain more profit from sponsorships, advertisements, appearance fees, and overseas royalties. Although the traditional B2C (Business to Consumer) model had been impacted by the digital age, entertainment companies have managed to look for alternatives to guarantee revenue maximization through the B2B (Business to Business) model (Oh and Park 2012: 383).

In conclusion, the digital age has slightly affected the CD market, but it has also driven artists and music producers to be creative music-wise and business-wise in order to stand out from the oversaturated music industry. More importantly, it has lessened the distance between artists and their fans.

O, Daeyeong. “(Paekteuchekeu) Gasu 0.42 won…’eumwon suik baebun’ jeokjanghanga? [(Fact check) Singer 0.42 won…’Music revenue distribution’ appropriate?].” JTBC News, Aug. 21, 2017. http://news.jtbc.joins.com/article/article.aspx?news_id=NB11510500.

Oh, Ingyu, and Gil-Sung Park. “From B2C to B2B: Selling Korean Pop Music in the Age of New Social Media.” Korea Observer, Vol.43, No.3 (2012): 365-397.

“translatability”, where American entertainment mannerisms were adopted by Korean performers such as ‘stage manner’ and ‘showmanship” (Ibid.). The stage presence of K-Pop idols today, such as the incorporation of complex choreography and charismatic stage presence is an aspect of K-Pop that fueled its global domination.

“translatability”, where American entertainment mannerisms were adopted by Korean performers such as ‘stage manner’ and ‘showmanship” (Ibid.). The stage presence of K-Pop idols today, such as the incorporation of complex choreography and charismatic stage presence is an aspect of K-Pop that fueled its global domination. audience but also to display the exoticism of language for young Korean audiences. There are many rap competitions shows, such as “Highschool Rapper” and “Show Me the Money” that exemplify this incorporation of foreign language into lyrics. By watching the reaction of the other contestants, the rappers who use English in their raps are clearly seen as more impressive lyricists.

audience but also to display the exoticism of language for young Korean audiences. There are many rap competitions shows, such as “Highschool Rapper” and “Show Me the Money” that exemplify this incorporation of foreign language into lyrics. By watching the reaction of the other contestants, the rappers who use English in their raps are clearly seen as more impressive lyricists.

There are two ways for idols to keep Korean fans content, while avoiding backlash from international audiences. One is for idols to avoid talking about political issues completely, and ensuring that all of their produced content including music, scripts, and social media posts are as neutral as possible. While this is effective for the most part and the strategy most idols tend to use, it may seem unpatriotic to some which is bad if the idol is more popular in Korea than anywhere else. The other method is avoiding any explicit public stances on issues involving other regions, while using media to promote and celebrate Korean history. This naturally leads to fans, both domestic and international, talking about the issues themselves, without getting the idol involved.

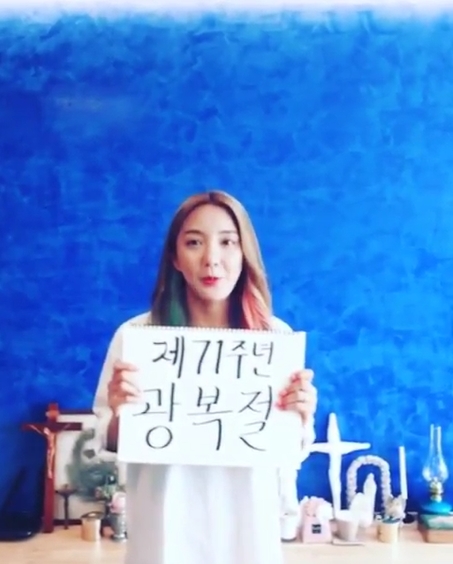

There are two ways for idols to keep Korean fans content, while avoiding backlash from international audiences. One is for idols to avoid talking about political issues completely, and ensuring that all of their produced content including music, scripts, and social media posts are as neutral as possible. While this is effective for the most part and the strategy most idols tend to use, it may seem unpatriotic to some which is bad if the idol is more popular in Korea than anywhere else. The other method is avoiding any explicit public stances on issues involving other regions, while using media to promote and celebrate Korean history. This naturally leads to fans, both domestic and international, talking about the issues themselves, without getting the idol involved. To understand the second method and to see why it is effective, we must see an example. Bada, a popular Korean singer from the group S.E.S., made several posts on social media in 2016 of her celebrating Gwangbokjeol, the Korean Independence Day. Korean fans were happy to see their idol show patriotism while the Japanese fans had no issues with her celebrating a national holiday and talking about history. Not only that, any international fans that were previously unaware of Korea’s colonial past could learn about it.

To understand the second method and to see why it is effective, we must see an example. Bada, a popular Korean singer from the group S.E.S., made several posts on social media in 2016 of her celebrating Gwangbokjeol, the Korean Independence Day. Korean fans were happy to see their idol show patriotism while the Japanese fans had no issues with her celebrating a national holiday and talking about history. Not only that, any international fans that were previously unaware of Korea’s colonial past could learn about it.