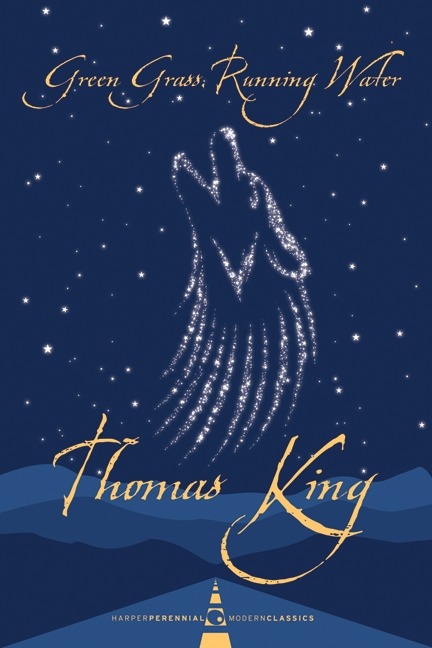

Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water blends Western literary fiction with the oral stories of Indigenous people. For this week’s assignment, each student was given a specific set of pages from the novel with the intent of discovering as many of King’s subtle (and not-so-subtle) allusions and cultural crossovers as possible. I have been given pages 12-24, which has a plethora of names and references. As I break down the significance of these various names, I will be relying heavily on Jane Flick’s “Reading Notes” for King’s novel.

Ishmael, Lone Ranger, Hawkeye, and Robinson Crusoe (p. 12-15)

Each of these four names holds a rather significant place in Western literature and entertainment. Unlike their Western namesakes though, in Green Grass, these are the names of four Aboriginal men – a clear fusion on King’s part of Western and Indigenous fictional characters. “Ishmael is a character from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, who begins the story with one of the most famous opening lines in American fiction: ‘Call me Ishmael'” (Flick 143). “Ishmael” is also a Biblical character: he is Abraham’s first son.

Lone Ranger is a famous Texas Ranger character from American historical folklore. At the time, he represented the American fantasy of what the American frontier was like. In taking the name of this famous American character, King is telling the story of Lone Ranger from an Indigenous perspective. In doing so, he addresses some of the issues that are inherent in the original literature, which Chadwick Allen outlines in “Hero with Two Faces: The Lone Ranger as Treaty Discourse”:

In the popular White American imagination, treaty discourse inscribes a brief moment of balance in the citizenry’s and the government’s history of Indian-White relations (only vaguely known or understood by most White Americans), a pause between what is seen as the ignoble past of conquest and the present disaster of Indian policy…Essentially mythic, treaty discourse sanctions White American fantasies of an idealized treaty moment. Central to these fantasies is an available and thus knowable Indianness: an Indianness defined as racially “pure” but organized in non-Indian terms. In the classic Lone Ranger-Tonto pairing, the idealized Indian Tonto operates as an “island of tribalism” in a frontier imagined as overwhelmingly White, supervised and supported by the “governmental” authority of the idealized White Ranger. (Allen 612)

Hawkeye, or Natty Bumppo, also a famous Caucasian character from the American frontier, is another instance of King trying to rectify the issues in past American stories. In his paper on the significance of able-bodied Natty Bumppo as symbolic of American notions of ability and superiority, Thomas Jordan writes:

…[there is] a binary opposition between the disabled and the able-bodied in order to mark a point of separation between Natty Bumppo and his Native American friend and counterpart, Chingachgook. Here, Chingachgook occupies a disabled identity in order to facilitate his ultimate removal from the novel. Chingachgook’s physical frailty is a narrative device that foreshadows his eventual suicide and symbolically positions the end of the Native American race as the result of a process of natural selection rather than violent British and US imperialism.

Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe is an important character in English literature, with his story marking the rising popularity of realistic fiction. Once again, however, Western superiority takes precedent over Indigenous people in Defoe’s narrative as Flick writes: “[Crusoe] is aided by his Man Friday, the “savage” he rescues from cannibals, and then Christianizes.” Crusoe enacts what colonizers assumed was the best course of action for people they viewed as “savage”. Again, there is an issue to be redressed here and King does so through his Indigenous Robinson Crusoe.

Dr. Joseph Hovaugh (p. 16-17)

One of the few references I actually caught on my own without Flick’s help, Dr. Joseph Hovaugh’s name is actually a homophone for “Jehovah“. On these two pages, the doctor spends his first appearance in the novel contemplating his garden, a garden that most likely refers to the Garden of Eden. (Flick writes on page 143: ” Note also that Joe Hovaugh’s garden is in the east, in Florida: “And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden” (Gen.2:8).”) The escape of the four “Indians” from Dr. Hovaugh’s institution can be interpreted as the escape of Indigenous people from the imposed Western dominance, which the doctor represents.

Alberta Frank, Henry Dawes, John Collier, Mary Rowlandson (p. 18-21)

In her “Reading Notes,” Flick succinctly describes the significance of Alberta’s name along with the importance of her students’ names, all of whom hold a place in history, and whose behaviour in the novel reflect their real-life counterparts. Flick writes that not only is Alberta’s name a reference to the Canadian province where King has lived and taught for a decade, but Alberta’s last name is also indicative of her honest and direct character. Flick posits on page 144 that “King may also have drawn her name from Frank, Alberta, on the Turtle River. This town was a major disaster site, buried by the famous Frank Slide of 1993.”

Henry Dawes created the Dawes Act of 1887, “which privatized communally held Indian land and led to the dispersal of Indian lands in the U.S., estimated at more than a million acres…much trickery and deeding away of lands followed this enactment” (Flick 144). In these pages, Henry Dawes is depicted as the worst student of the group, having fallen asleep in Alberta’s lecture and being the one she picks on to answer a question about the lecture.

John Collier became the Commissioner of Indian Affairs under President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. He introduced the idea of a “New Indian Deal” in 1934, but despite his “sympathetic [view of] Indians, he still depicted them in a stereotypical manner“. In King’s text, Collier seems to be the only student engaging with Alberta’s lecture, though even still, his engagement is far from scholarly, with one of his two responses being a simplistic “Oh, bummer” (King 19).

Mary Rowlandson was a colonial American woman who was captured in 1676 by Native Americans an held for several weeks before being ransomed. A few years later, a narrative of her capture and release was published. Considered an important point of reference by colonialists at the time, the work held heavy tones of revulsion for Indigenous people and described them using words such as “ravenous beasts”, “wretches”, and “heathens”. King recreates this historical character as a student who is unconcerned with details in Alberta’s class.

Babo Jones, Sergeant Cereno (p. 23-24)

Flick notes that Babo is a reference to the character of the same name in Herman Melville’s story “Benito Cereno,” and that Sergeant Cereno is a reference to the story’s eponymous protagonist. In Melville’s tale, Babo is an African-American barber who becomes a slave revolt leader on the story’s ship. In the interaction between the Sergeant and Babo regarding the details surrounding the Indians’ disappearance, there are references to water and ship a few pages later, as Babo observes the Pinto outside the window flooding. “Pinto”, Flick observes on page 146, is a play on the name Pinta, which was the name of Columbus’ ship. The reference to flooding is not only a nod to Melville’s story, but it is also one of the many Biblical inclusions in King’s attempt to blend Western narrative with Indigenous story-telling.

Works Cited Continue reading