The Ecosystem Services (ES) concept was first introduced in the 1960’s and 70’s by naturalists like Eugene Odum(1) and Paul Elrich(2) as a means to illustrate the economic value humans derive from natural systems. Nowadays the concept has become ubiquitous in conservation, economic and environmental policy and incorporating the externalities of the emerging ‘Blue’ economy of our oceans is a hot button issue. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature has recently published a report outlining how policymakers and managers should best study and model ES. Last year, Kenya hosted a Sustainable Blue Economy conference supported by the United Nations Development Programme and China and the EU signed an ocean partnership agreement outlining their intentions to improve ocean governance and support crucial ES. ES have been fully accepted into the mainstream of conservation policy, so it’s vital that we understand how they fit into improving ocean conservation and sustainability. In this piece, I will outline the common tools through which ES have recently been incorporated into capitalist systems, their downsides for economics, conservation and sustainability and the role that I believe ES should play in shaping future ocean policy.

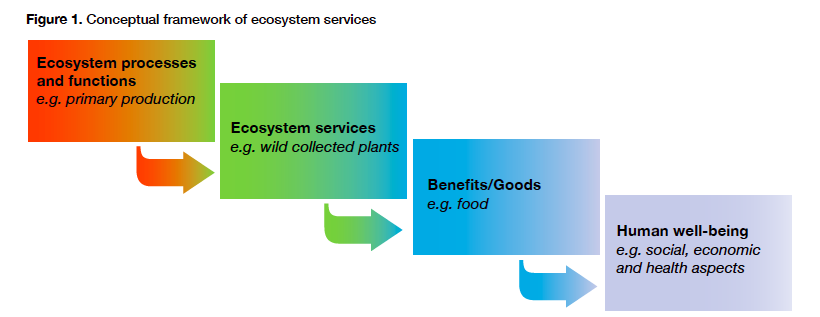

An IUCN framework of the Ecosystem Services concept. © IUCN 2018.

ES are often implemented through market-based policies that require actors that contribute to environmental degradation pay a cost associated with the negative externalities of their actions, commonly known as the ‘polluter pays principle’, or where positive externalities such as reforestation are rewarded, like the UN’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation program. But effectively implementing ES models in an ocean conservation context first requires addressing the commodification of ES, who these markets serve, and whether these market-based schemes are the best use of ES. Solutions that ecompass ocean ES like blue Carbon markets or ecosystem credits also entrap these services into volatile, inequitable capitalist markets (3). Who benefits from these ES and who benefits from their exploitation is also a difficult question– exploiting a natural resource unsustainably extracts and concentrates capital into the hands of the irresponsible instead dispersing its value to the commons. ES also won’t operate on anthropocentric timescales just because we’ve incorporated them into a market system; storm surge protection, carbon sequestration and fisheries production can change at timescales inconvenient to capitalists and investors.

Photo of a seagrass meadow, which are important sinks for blue Carbon in the oceans. © Jean-Marc Kuffer.

Policymakers attempting to reign in the wild west of ocean resources would do well to avoid the mistakes of market-based solutions used in terrestrial systems. ES should be a tool for authoritative bodies to determine the costs and benefits or a particular development or extractive effort and decide whether the disperse benefits of the ES outweigh the concentrated benefits of its exploitation. Governing bodies have the capability to take a long-term approach to determining conservation and resource management strategies that many corporations and individuals do not. Therefore, in the race to instil law, order and sustainable practices at the high seas or in coastal ecosystems ES should be used to act above capitalist markets, rather than within them, in order to ensure the long-term ecological and economic sustainability of our oceans.

References

Elrich, P.R. & Ehrlich, A.H. (1981). Extinction: The Causes and Consequences of the Disapearance of Species. New York: Random House.

Gómez-Baggethum, E. & Ruiz-Pérez, M. (2011). Economic valuation and the commodification of ecosystem services. Progress in Physical Geography, 35(5): 613-628.

Odum, E.P. & Odum, H.T. (1972). Natural areas as a necessary components of man’s total environment. Transactions of the Thirty Seventh North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference, (37):178-189.