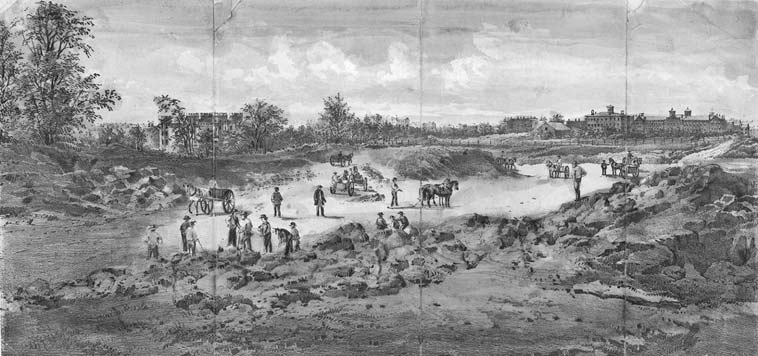

In 1857, Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux won the design competition for New York’s iconic Central Park with their “Greensward Plan”. This design carried a pastoral vision and the stated intent to “supply to the hundreds of thousands of tired workers,who have no opportunity to spend their summers in the country, a specimen of God’s handiwork.”1 Embedded in this intent is a notion of the construction of the park as a sort of uncovering, a return to the platonic state of the land. However, prior to the construction of the park, this vast 843 acre swath in the heart of the city was an unrecognizable landscape with a rich and complex political and ecological history. Land clearing for the construction of the park operated on a multiplicity of levels from an attempted cultural reset regarding the appropriate use of public lands, to the removal of the Black Seneca Village Community, to a drastic biophysical transformation of the land itself. Within its capacity as one of the most ambitious public works projects of the 19th century, the story of Central Park also is one of class conflict, white supremacy, and Black land dispossession.

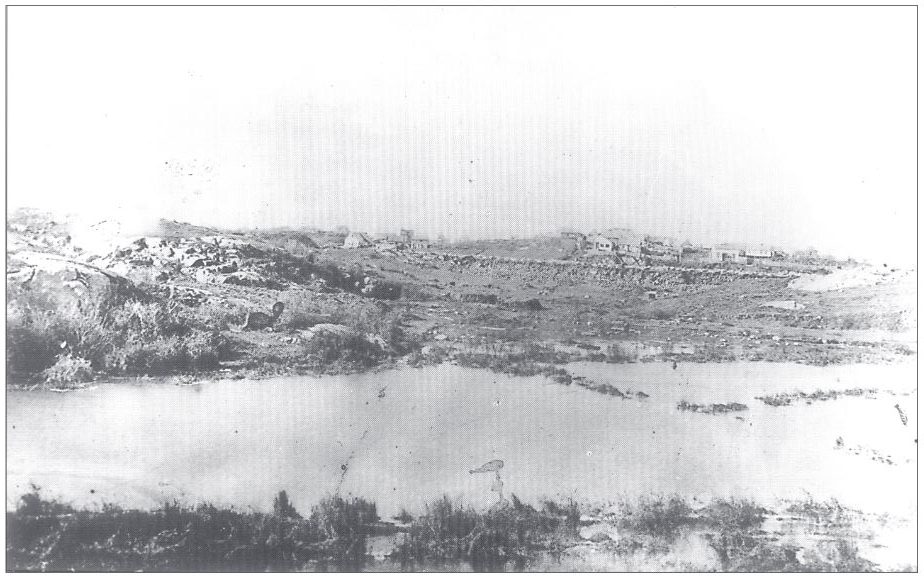

Prior to colonization by Dutch settlers, the Lenape first nation occupied this territory and shaped the landscape through large-scale agriculture for centuries. The original swampy, rocky, and uneven landscape is a far cry from Olmstead and Vaux’s vision.2 By the time construction began, disease and colonial violence had pushed almost all the Lenape population from the site, leaving Olmstead and the city with two primary impediments: a new generation of residents of the site and the terrain and ecology of the site itself. The Greensward Plan was heavily inspired by the English gardens of the time which eschewed “formal, geometric landscapes… linear walks, manicured trees and topiary, symmetrical beds, and elaborate fountains” in favour of a more “informal garden composed of rolling greensward, informal groupings of trees, serpentine paths, and still ponds.”3 This aesthetic shift may be traced to the enclosure movement, during which public lands were compartmentalized and privatized for commercial agriculture. As neatly separated and geometrically ordered landscapes became more commonplace and further associated with labour, a new nostalgia arose for a previous, less ordered and more sweeping landscape.4 In order to impose this vision upon such a disparate landscape and ecology, Olmstead began an ambitious campaign of blasting, soil augmentation, transplantation, road and bridge construction, swamp transformation, and the creation of artificial lakes. This labour necessitated some twenty thousand workers, thousands of horses, tons of gunpowder, and massive amounts of coal.5 An important part of this process was the import of Peruvian guano used as fertilizer, harvested mostly by enslaved Chinese labourers during the final decade of traditional US slavery.6 This practice exemplifies the cognitive dissonance of Olmstead’s vision: an enslaved labour force from the other side of the world rapidly harvesting a fertilizer thousands of miles from the Park, all toward the creation of a “natural” landscape.

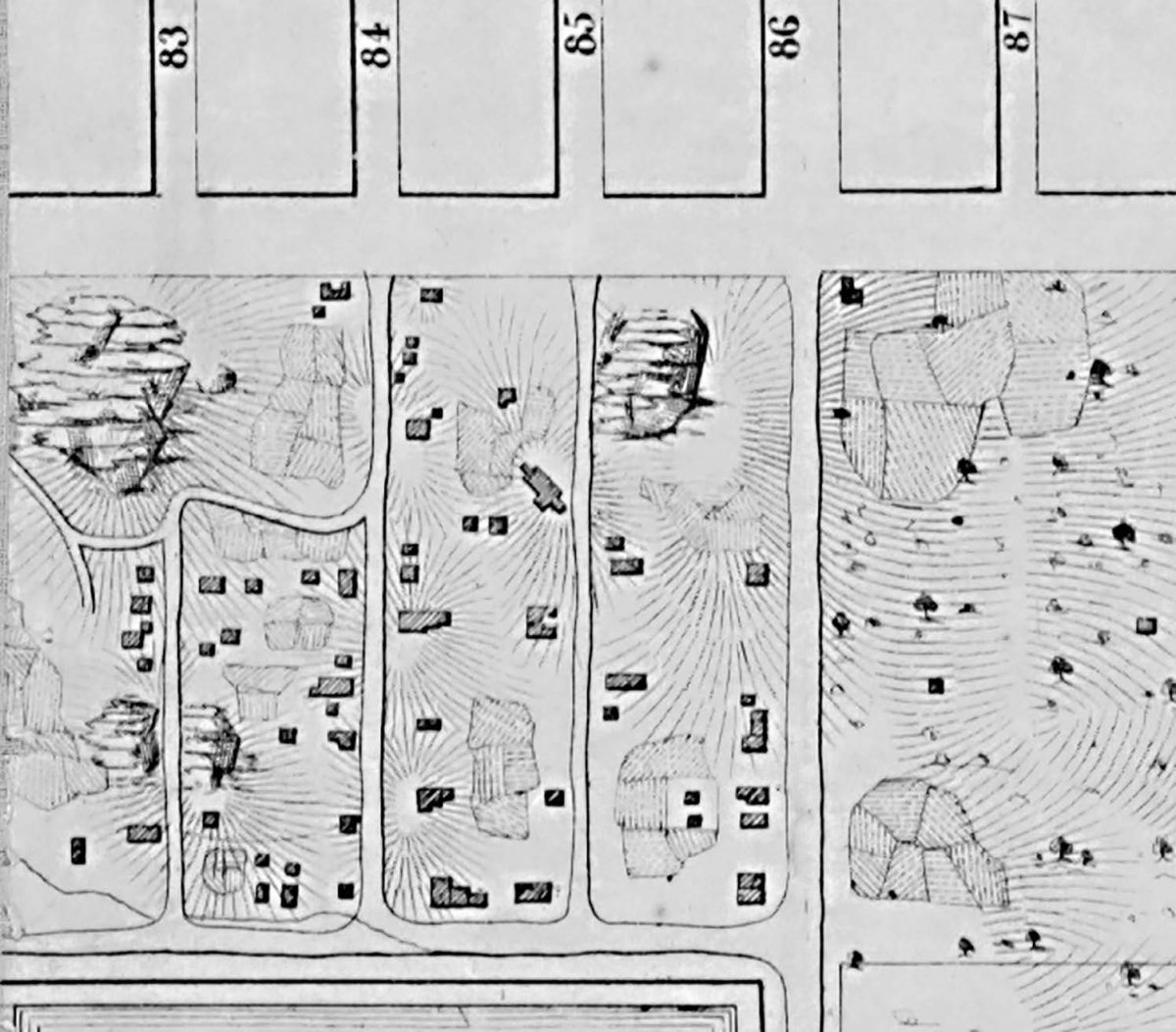

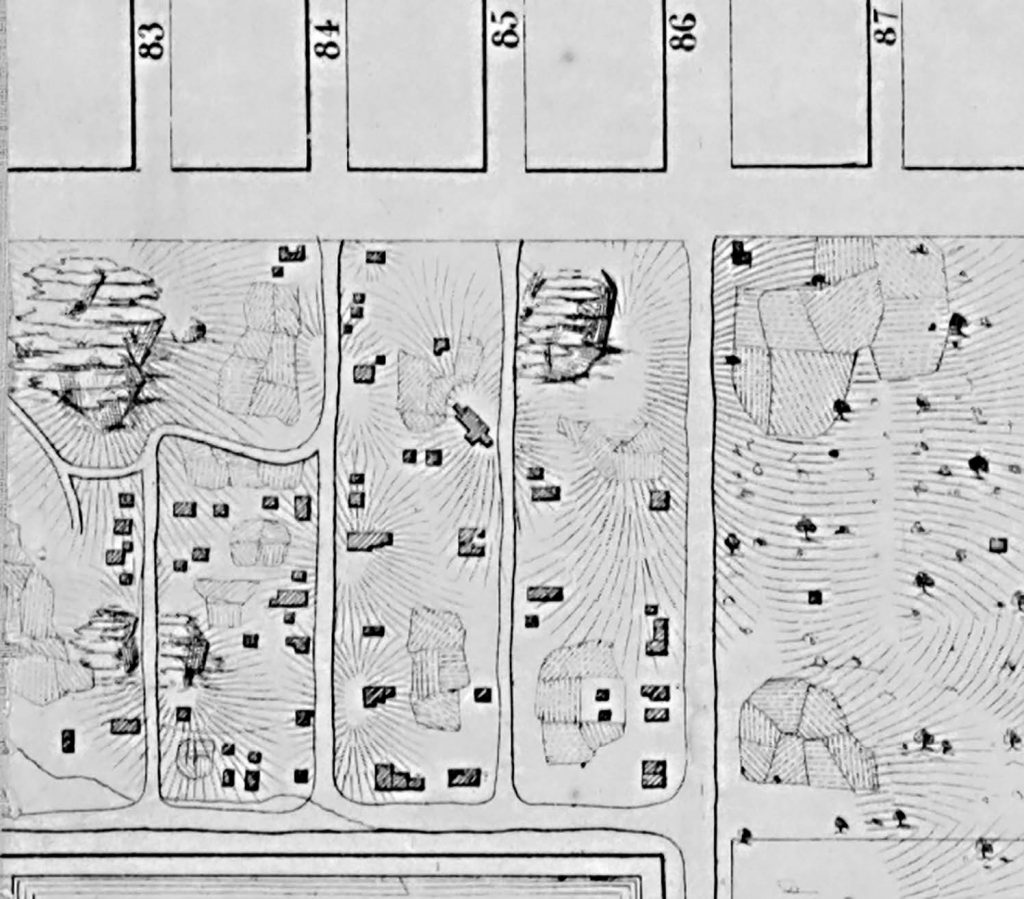

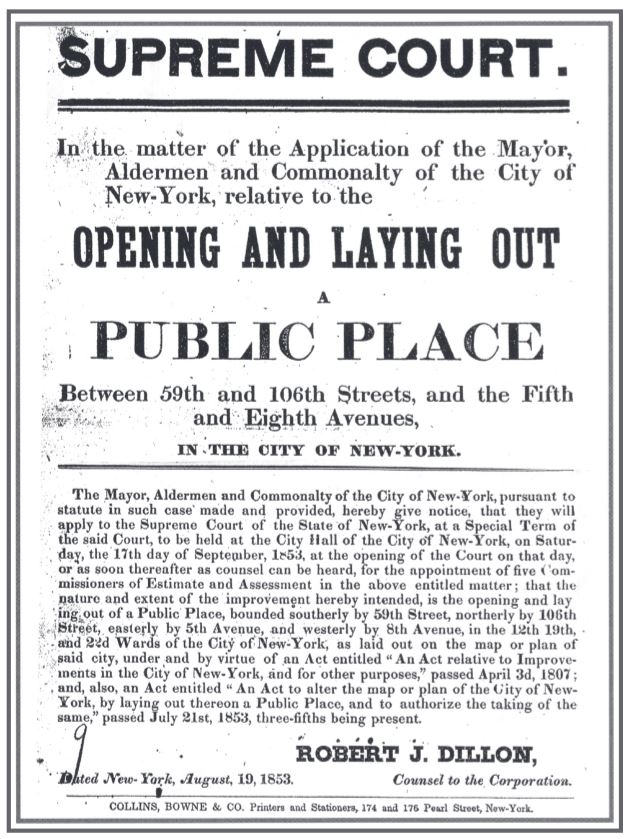

One of the first steps toward Olmstead’s transformation of the land was the removal of its occupants. From emancipation in New York state in 1827 through 1857, the current site of Central Park was home to Seneca Village, an emancipated Black community between 82nd and 89th street and 7th and 8th avenue. This thriving community of roughly 300 people was unique in that many of its residents owned their homes as it was outside the range of larger white-owned real estate developments which would not sell to Black residents.7 The community originated with the purchase of land for a burial site by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and quickly expanded to include several homes and two more churches. Two of the churches were Black and one was integrated.8 This was an extremely unique circumstance for the time. Some important factors toward the viability of the site for a community included available fresh spring water and firewood as well as an ample supply of fish from the Hudson River.9 Seneca Village also had a school, “The Colored School #3” housed in the African Union Church. Remarkably, by 1850 nearly 75% of children in the community attended school. Before the construction of Central Park, another school was planned.10 Most of the population worked in service jobs or as unskilled labourers, but due to the prevalence of homeownership and education, the Seneca Villagers may be thought of as members of a Black middle class.11

of The Central Park, New York, 1857, Baker, New York).

The significance of Black homeownership in this context absolutely cannot be overstated. In 1821, an amendment to the New York state constitution provided suffrage for African American men who owned at least $250 worth of property, though the same restrictions were phased out for white men. Although many of the lots in Seneca Village were sold for as little as $50, this provision still provided suffrage to many of the residents.12 The amendment, seemingly intended to provide titular suffrage without substance due to the difficulty of real estate acquisition by Black New Yorkers. However, it became a viable means for some members of the Seneca Village Community to gain voting rights more than forty years before federal emancipation. Outside of the community, in the mid 1850s the contemporary press painted it as a slum and a nuisance, claiming that it was “occupied by squatters whose homes were so dirty that death himself hesitates to enter”.13 This negative, deeply racist portrayal of Seneca Village eased potential public outcry over the city’s 1858 motion to claim the land through right of eminent domain in order to make way for the park. All of the residents were evicted from the site of the future park. Property owners were given nominal compensation for the loss of their homes, but subsequently lost any voting rights they may have held, as there was almost nowhere else in the city where Black residents would have had the opportunity to buy homes.14 Wall, Rothschild, and Linn note, “As Americans, we tend to believe that land ownership supplies security in access to place, but of course this has repeatedly been shown to be false, especially for those who are disempowered. Seneca Village’s residents were evicted through the use of eminent domain, just as today the neighborhoods of the politically powerless continue to be destroyed under the banner of urban renewal in cities across the United States.”15

This history went largely unrecognized for almost 150 years after the destruction of the community. Recent archaeological efforts and research led to a plaque and designation memorializing the community at its former site in 2001. Graves from the three churches likely remain under Central Park today.16 Seneca Village, a groundbreaking, vibrant, and unique case of antebellum Black self-determination in the United States was snuffed out for the mission of public leisure and property value. In examining this history, one must ask what “public” the park served in 1858, what “public” the park serves today, and how Central Park can reconcile with the damage its birth inflicted upon so many.

It is not merely a question of losing African American history; it is a matter of writing an accurate history. If you leave out this story, you are not really writing New York (or even American) history.17

Notes:

1. Jane Hutton, Reciprocal Landscapes : Stories of Material Movements , 1st ed. (Routledge, 2019), 27.

2. Colin Fisher, “Nature in the City: Urban Environmental History and Central Park,” OAH Magazine of

History 25, no. 4 (2011): 27-28.

3. Fisher, 28.

4. Raymond. Williams, “Enclosures, Commons, and Communities,” in The Country and the City (London:

Chatto and Windus, 1973), 101–6.

5. Fisher, “Nature in the City,” 28.

6. Jane Hutton, Reciprocal Landscapes : Stories of Material Movements , 1st ed. (Routledge, 2019), 48.7. Diana Wall, Nan Rothschild, and Meredith Linn, “Constructing Identity in Seneca Village,” in

Archaeology of Identity and Dissonance , ed. Diane George and Bernice Kurchin, Contexts for a Brave

New World (University Press of Florida, 2019), 157–58.

8. Wall, Rothschild, and Linn, 158.

9. Diana Wall et al., The Seneca Village Project Working with Modern Communities in Creating the Past ,

Places in Mind , 1st ed. (Routledge, 2004), 103.

10. Wall, Rothschild, and Linn, “Constructing Identity in Seneca Village,” 163–64.

11. Wall, Rothschild, and Linn, 166.

12. Wall, Rothschild, and Linn, 158–59.

13. Wall et al., The Seneca Village Project Working with Modern Communities in Creating the Past , 103.

14. Wall et al., 103.15. Wall, Rothschild, and Linn, “Constructing Identity in Seneca Village,” 175.

16. Diana Wall et al., The Seneca Village Project Working with Modern Communities in Creating the Past ,

1st ed. (Routledge, 2004), 115.

17. Olivia Ng, “Seneca Village Perceptions” (Senior Thesis, Department of Anthropology, New York,

Columbia University, 1999).

Works Cited:

Fisher, Colin. “Nature in the City: Urban Environmental History and Central Park.” OAH Magazine of History 25, no. 4 (2011): 27–31.

Hutton, Jane. Reciprocal Landscapes : Stories of Material Movements. 1st ed. Routledge, 2019.

Ng, Olivia. “Seneca Village Perceptions.” Senior Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Columbia University, 1999.

Wall, Diana, Nan Rothschild, Cynthia Copeland, and Herbert Seignoret. The Seneca Village Project Working with Modern Communities in Creating the Past. 1st ed. Routledge, 2004.

Wall, Diana, Nan Rothschild, and Meredith Linn. “Constructing Identity in Seneca Village.” In Archaeology of Identity and Dissonance, edited by Diane George and Bernice Kurchin, 157–80. Contexts for a Brave New World. University Press of Florida, 2019.

Williams, Raymond. “Enclosures, Commons, and Communities.” In The Country and the City, 96–107. London: Chatto and Windus, 1973.