In 1773, the Raj began once the Crown appointed the first official governor-general of India to oversee the operations of the private British East India Company (BEIC); this was the British effort to bring the Enlightenment to India with their primary focus being on Calcutta, a city now known as Kolkata.1 Initially, Calcutta was a swamp that was then transformed by the BEIC and the wealth it brought, into a massive port with colonial governmental structures and mansions, then becoming a comparable city to London. From this, Calcutta became the second most important city in the British Empire, with London being the first. This transformation of Calcutta became more robust once Lord Richard Wellesley became the new governor-general and decided to construct a new building to embody his authority – this began the construction of a new Government House. English colonialism in Calcutta, India relies on the Government House (1803) to serve as an architectural symbol that provides visual confirmation of imperial solidity to transform a straggling city into an imperial metropolis; this confirmation is delineated by the Government House being a symbol of spectacle, bestowing contempt and fear, and through its surrounding expansions.

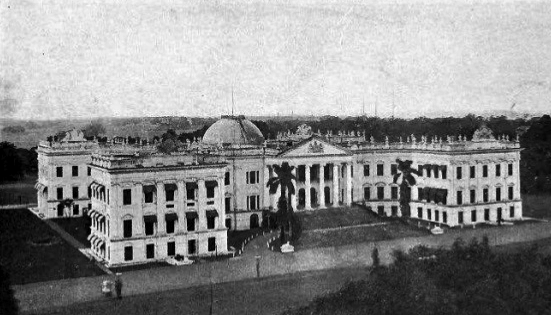

Government House has made known to perform as an architecture of spectacle to promote English colonialism in Calcutta. The spectacle is defined as a reaction to reality and it is the cohesion between the two that creates an experience. Chelsea Adelson states that ‘the result is a more complex: where reality is understood by the images, and the spectacle is understood through the real.’2 The plan for the Government House was prepared by Lieutenant Charles Wyatt, which was based on James Paine’s design of Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, England.3 Charles Wyatt prepared these plans with spectacle in mind.4 To begin with, the Government House stands as an idealized object in space due to the overall size of the massing. At the front of the building, it resembles the look of the Pantheon with rectangular form and a gabled roof of a triangular pediment supported by a colonnade on all sides. This neoclassical style symbolizes importance and stimulates a sense of grandeur. The porch is conventional in design, but the body of the building, an immense space that splits into four wings, and a large dome at the rear-end of the building, all resemble the Kedleston Hall. By resembling the Kedleston Hall, the Government House is bringing England to India; directly symbolizing imperialism, and in the combination of being a spectacle, it becomes a prominent feature of the city that signifies a colonized city. Therefore, in Calcutta, the architecture of spectacle appears to be for more than capital gain and foreign attraction, but rather for the promissory value of the city and political significance and recognition.

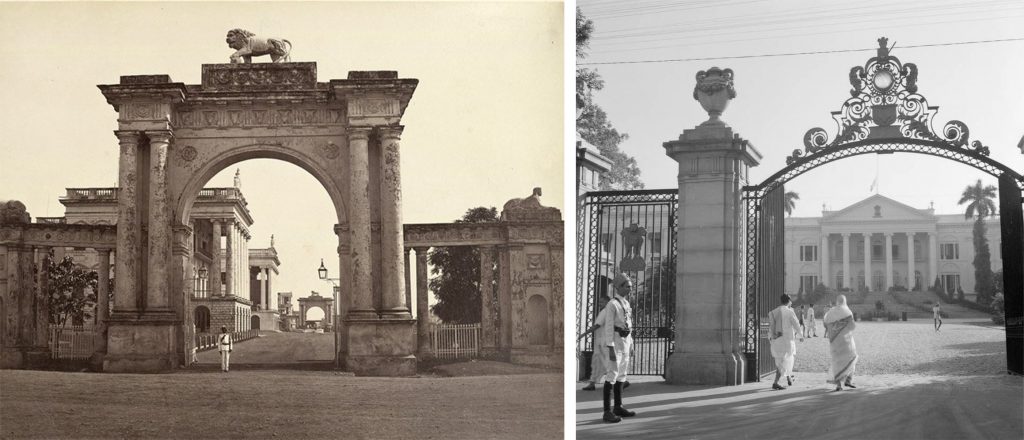

While to the observer of the Government House it looks like a spectacle, the house also delineates feelings of contempt and fear to solidify imperialism. In this instance, the ideology of the British rule was ‘to create a permanent gulf of contempt and fear between the ruler and the ruled,’5 which relayed as the imperial governing class having no expectations to socialize with commoners, but rather keep them at arms distance. Due to the social life, the British had to accommodate, many compromises in the spatial arrangement were made by the British, even in stately buildings such as Wellesley’s palace. The interior of the Government House was segmented into rooms for privacy with perforated colonnades designed specifically to allow constant servant access to all spaces, however, the visibility of the retinue of servants was limited to the occupiers of the house. This conveys a literal divide between the ruler and ruled and insinuates contempt and fear into the ruled through the spatial real estate that they could occupy. Despite the separate servant quarters, Cornwallis’s wife, the wife of a later governor-general, is still said to have complained that the Government House had no place she could call her own.6 In favour of protecting sociability and symbols of imperialism, the Government House was built with demarcating wrought-iron railings, masonry walls, and gates, also designed after European pattern books.7 Based on images, the walls and gates become an extension of the building and sets boundaries between the building and the outside world; thus, evoking uneasiness when entering past the gates as a member, not of the ruling class. This contempt and fear appear to be a strategy to confirming imperial solidity, stability, and even majesty, and thus symbolizing that ‘the physical occupation and control of space have been crucial to British imperialism.’8

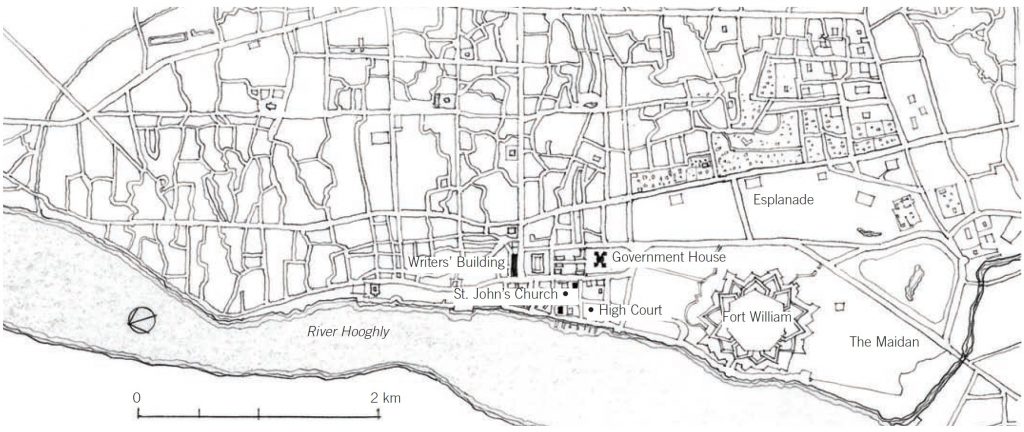

Also, visual confirmation of imperialism in Calcutta is evident through the expansion of the Government House and its surroundings. In general, the construction of the Government House was a seminal event in the development of Calcutta. It urged broad vistas, monuments, and other impressive buildings – ranging from official buildings to private houses – to be created along the Esplanade in an intentional effort to display wealth and power of the Government House, but also to complement the design of the Government House.9 Not only did the house symbolize power, but the surroundings did as well. This allowed foreign visitors as well as Indians to have an unobstructed view of the house and observe the spectacle and supremacy of the emerging British Empire. To an even greater degree, the siting of the building and its expansion disrupted a major street, causing all traffic a lengthy detour in the heat around the extensive grounds in a routinely act of respect to imperial authority. Due to the Government House, Calcutta became the first city where the British could build a unified and coherent center of power and knowledge through architectural symbolism and town-scaping.10

By 1810, European sections of Calcutta took the appearance of a classical and imperial city, which was an unprecedented instance of imposing architecture as a symbol of imperialism to a straying city that initially was a swamp. Through this, European ideas of architecture, planning, town-scaping, and layout were employed throughout other cities in India.11 The construction of Lord Richard Wellesley’s Government House triggered this process as it solidified English ruling through the grandeur nature it held and promissory value it gave the city, delineating space by ruler and ruled to evoke feelings of disdain, and curating a central space of power by expanding outwards from the Government House.

Notes

[1] Ching, Francis D. K., Jarzombek, Mark M., and Prakash, Vikramaditya. A Global History of Architecture. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2017: 634.

[2] Adelson, Chelsea. “The real, the spectacle, and the in-between: architecture as a stage for reality.” Architecture Theses. Paper 86. 2012: 11.

[3] Sen, Siddhartha. Colonizing, Decolonizing, and Globalizing Kolkata: From a Colonial to a Post-Marxist City. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017: 63.

[4] Ching, Jarzombek, Prakash. A Global History of Architecture. 2012: 634.

[5] Chakravarty, Suhash. The Raj Syndrome: A Study of Imperial Perceptions. Delhi: Chanakya Publications, 1989: 52.

[6] Ching, Jarzombek, Prakash. A Global History of Architecture. 2012: 634.

[7] Chattopadhyay, Swati. “Blurring Boundaries: The Limits of “White Town” in Colonial Calcutta.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 59, no. 2 (2000): 157.

[8] Ashcroft, Bill. “Post-Colonial Transformation.” London: Routledge, 2013: 124.

[9] Sen, Siddhartha. Colonizing, Decolonizing, and Globalizing Kolkata. 2017: 66.

[10] Sen, Siddhartha. Colonizing, Decolonizing, and Globalizing Kolkata. 2017: 234.

[11] Sen, Siddhartha. Colonizing, Decolonizing, and Globalizing Kolkata. 2017: 234.

Bibliography

Blurring Boundaries: The Limits of “White Town” in Colonial Calcutta

Adelson, Chelsea. “The real, the spectacle, and the in-between: architecture as a stage for reality.” Architecture Theses. Paper 86. 2012.

Ashcroft, Bill. “Post-Colonial Transformation.” London: Routledge, 2013.

Chakravarty, Suhash. The Raj Syndrome: A Study of Imperial Perceptions. Delhi: Chanakya Publications, 1989.

Chattopadhyay, Swati. “Blurring Boundaries: The Limits of “White Town” in Colonial Calcutta.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 59, no. 2 (2000): 154-79. doi:10.2307/991588.

Ching, Francis D. K., Jarzombek, Mark M., and Prakash, Vikramaditya. A Global History of Architecture. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2017.

Sen, Siddhartha. Colonizing, Decolonizing, and Globalizing Kolkata: From a Colonial to a Post-Marxist City. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

Images

Cover Image. Idier, Nicolas. “Kang Youwei 康有爲 (1858-1927) and India: The Indian Travels of a Cosmopolitan Utopian.” The Indian Travels of a Cosmopolitan Utopian. January 01, 1970. Accessed February 14, 2021. https://books.openedition.org/cdf/7566.

Figure 1. The Victorian Web (www,victorianweb.org). Accessed February 14, 2021. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/empire/india/29.html.

Figure 2. অযান্ত্রিক. “Government House – Gateway, Calcutta, 1865.” Puronokolkata. June 07, 2014. Accessed February 14, 2021. https://puronokolkata.com/2013/10/29/gateway-of-government-house-calcutta/.

Figure 3. “India, North Gate of Raj Bhavan (Government House) in Kolkata.” CONTENTdm. Accessed February 14, 2021. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agsphoto/id/26185/.

Figure 4. Ching, Francis D. K., Jarzombek, Mark M., and Prakash, Vikramaditya. A Global History of Architecture. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2017: 632.