British Concession

The Former British Consulate-General Building in Shanghai, China is an example of colonial architecture that represented the Empire’s control over the city during Concession. As one of the first developed foreign buildings, it laid the foundation for other international investments and values, bringing their own architectural expressions along the Bund.1 The Opium Wars can also be seen as a catalyst for Britain’s initiation of invasion and its display of power. Though Concession also involved other European and American settlers, it was the British that mainly held dominion over the land.1 This analysis will thus examine the historical events that led towards the British Empire’s control over Shanghai, its influence over the development of the city through maps, and the establishment of the Consulate-General building and its architecture as a means of political expression.

Prior to the Opium Wars in 1839, the British Empire established itself as a major foreign trader along coastal China.2 However, the British were required to pay tributary taxes imposed on foreign trade under the Canton system, which fueled anger and resentment.1 To get around this, the British East India Company used profits from the trade of smuggled opium to pay the tax, which angered the Chinese.1 Furthermore, Britain’s control of tea and cotton exports significantly damaged Shanghai’s economy.1 All these factors cultivated a recipe for the British invasion of Shanghai.

After taking control of the major ports, the emperor called for peace in Nanjing, resulting in the Nanjing Treaty, signed in 1842.3 The treaty listed multiple articles that would give Britain the freedom to establish trading (Treaty) Ports and control tariffs on exports and imports.3 Specifically, one of the articles outlined the appointment of foreign consuls at Treaty Ports, who could freely communicate with officials in the Qing government.1 Additionally, British citizens in China were subject to British laws by the Consuls.3 This would ultimately remove China’s judicial control of British subjects, further solidifying Britain’s control over the city.

- Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

- Cary Y. Liu. “Encountering the Dilemma of Change in the Architectural and Urban History of Shanghai.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 73, no. 1 (2014): 118-36. Accessed February 16, 2021. doi:10.1525/jsah.2014.73.1.118.

- Bickers, Robert and Isabella Jackson. Treaty Ports in Modern China: Law, Land and Power, edited by Bickers, Robert, Isabella Jackson. London: Routledge, 2016. doi:10.4324/9781315636856.

Shanghai’s Development

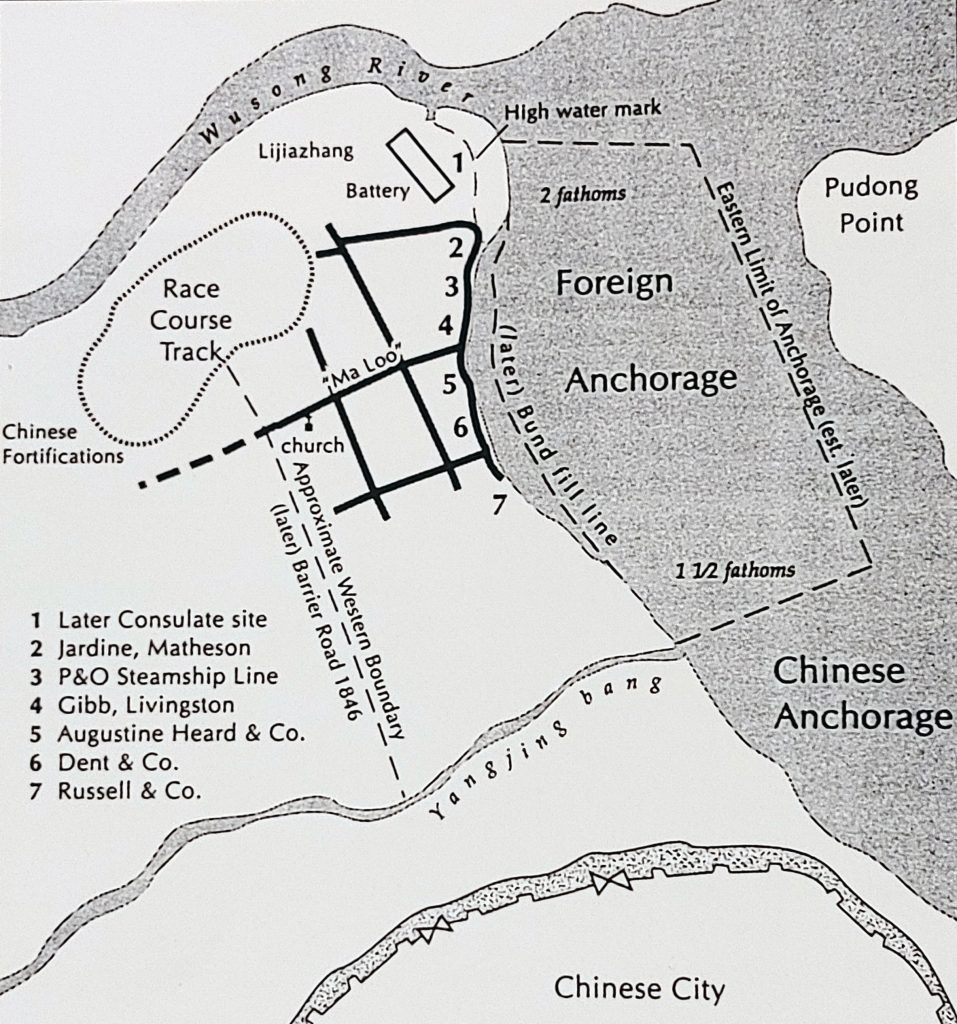

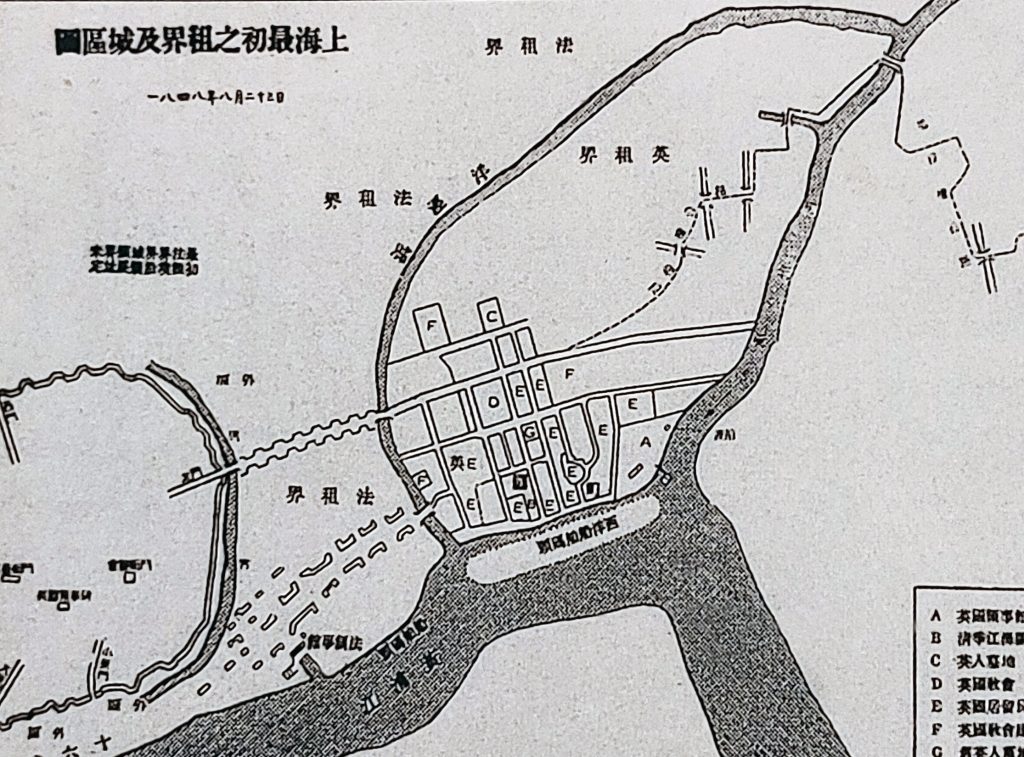

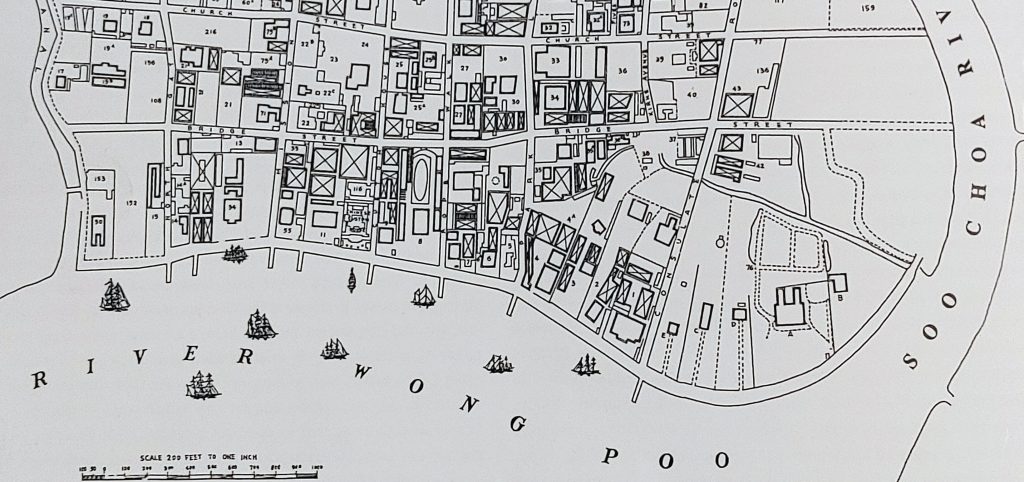

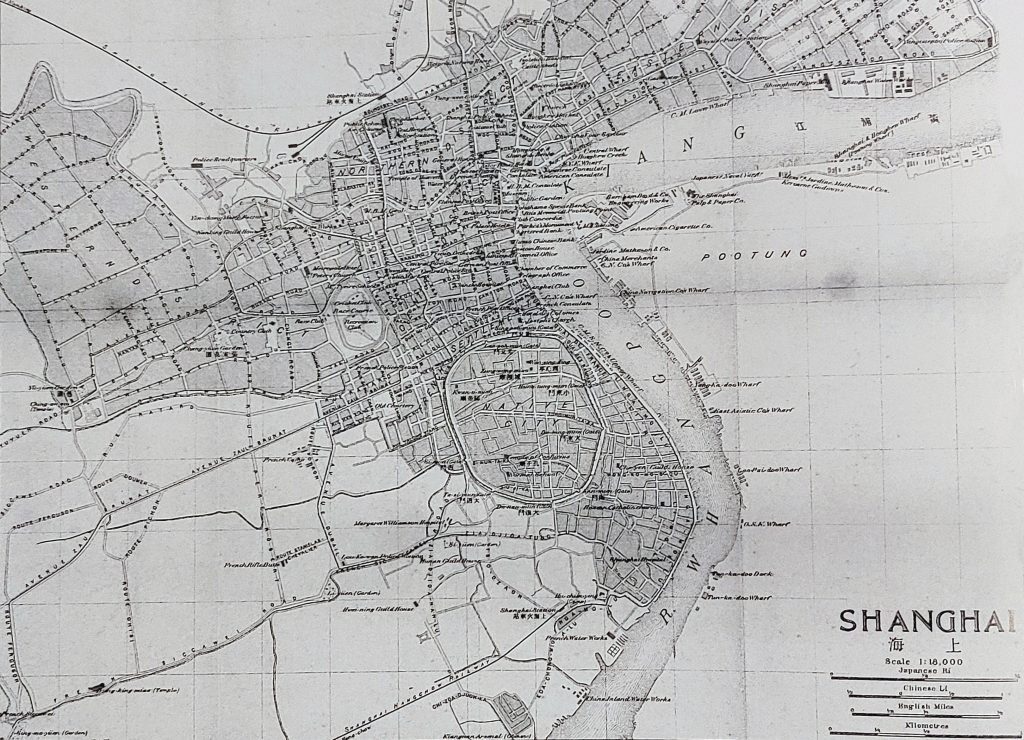

The establishment of the British Consulate fell under the Balfour Plan, and it was Consul George Balfour who was responsible for laying out Shanghai’s initial master plan.1 However, it was his successor, Rutherford Alcock, who established a permanent Consulate towards the head of today’s Bund at the confluence of the Suzhou and Huangpu River.1 The building exists today as the Former British Consulate-General Building. Based on early maps drawn of the city, it can clearly be seen that the British organized the site based on a strict grided street network noted by both British and Chinese mappings (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Their decision to develop along the coast made sense as it would have made trade easier and more efficient. Other maps, such as a British survey map from the 1890s revealed a more detailed network of roads including both Chinese and British institutions within Shanghai as it became more developed by Concession (Figure 5). This detailed map also shows the extent of the Empire highlighted in grey with scales with different measurement values. What this also shows is a biased map that divides the settlement with the outskirts that have not been developed and a means by which to understand the site through cartography; power is often associated with knowledge.

- Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

The Former British Consulate – General Building

Taking a closer look at the Former British Consulate-General Building in Shanghai reveals the Empire’s approach to architecture and colonial obsession with anglicizing the areas it occupies. Currently, the building sits as a historically protected two-storey structure constructed primarily out of stone, masonry, and timber.4 It was designed by R. Williams Crossman and R. H. Boyce in 1872, and constructed in 1873.4 What was interesting was that fired brick was not available in Shanghai then, thus construction had to rely on sun-dried brick.1 This would imply that the British had to adapt their architectural approaches in a foreign site in order to maintain their own expression. A structural analysis found that steel and concrete was also used,4 which would have been synthetic materials.

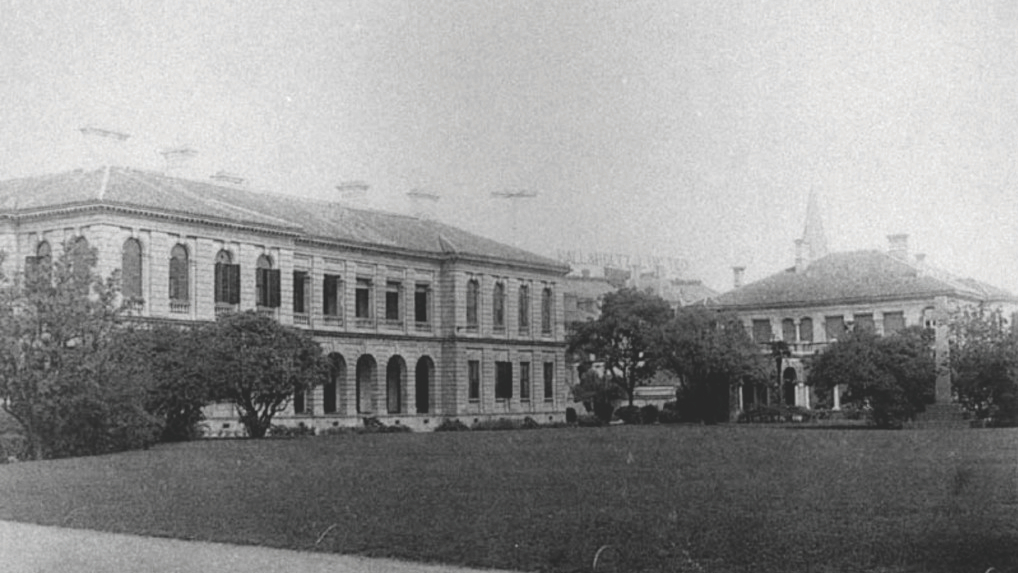

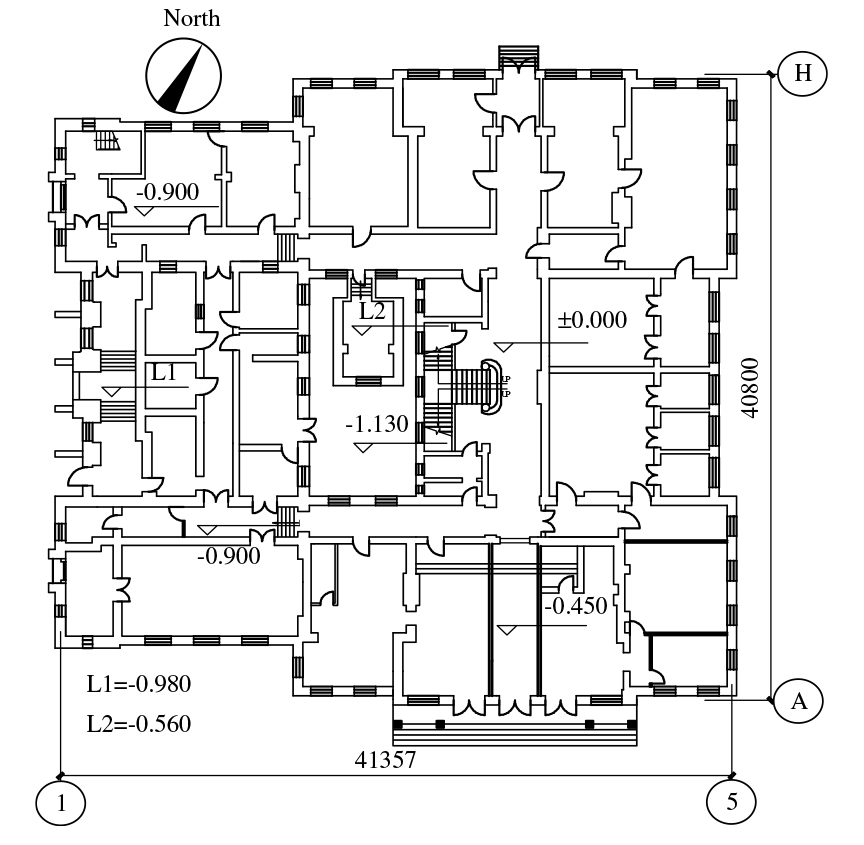

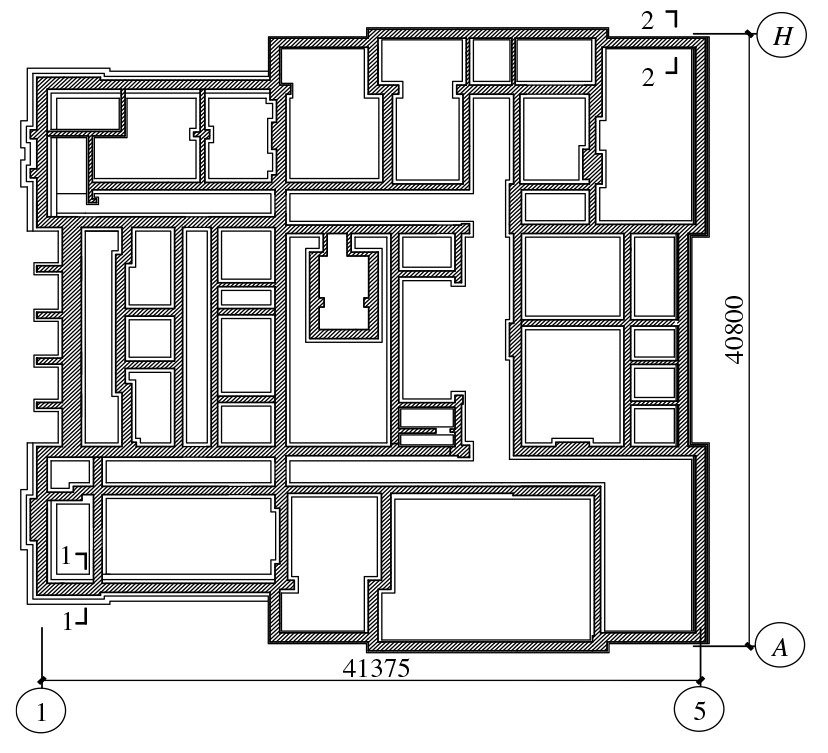

The formal expression based on the façade is that of the Neo Renaissance Style noted by its Greek and Gothic influences that are common throughout Europe and North America. This type of architecture was not found in China, thus the building would make a blatant statement about Britain’s arrival and solidification. The building also boasts an “H” type plan4 (Figure 6 and 7), which signifies symmetry and order. The majority of the rooms are located within each wing, with a central space primarily for accessibility, implying that a processional order was to be taken when circulating throughout this building. A connection related to procession could be made in that that the building’s location also represents itself as an entry point towards the trading center that is the Bund today. The Consulate-General building sits on a significant vegetated area with what appears to be a yard for leisure and gathering. This characteristic gives the British Consulate a greater significance compared to the other buildings in its vicinity. Ironically, this building has gone through multiple renovations towards restoration and operation.4 This leads one to believe that the Shanghai government did not want to erase its past, but wanted to preserve it, as with the rest of the buildings along the Bund.

- Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

- Gu, X, D Shang, B Peng, and X Li. “Structural Inspection and Analysis of Former British Consulate in Shanghai.” Structural Analysis of Historic Construction: Preserving Safety and Significance, 2008, 1537–43. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781439828229.ch179.

Reflection

In conclusion, there were many factors that led toward the establishment of the Former British Consulate-General Building in Shanghai. The frustration of the initial trade laws for Britain in China led to the Opium Wars, which opened an opportunity for invasion and Concession.1 As the city developed formally and politically, there was a need to establish a Consulate in Shanghai that led to an architectural standard which exists today.1 Through an examination of maps, one could delineate the extent of the Empire’s reach in the city and its values. Furthermore, the Consulate-General Building in particular, brought Victorian English styles of architecture to the city along Shanghai’s coast1 (Figure 8) that can be seen and experienced today along the Bund. Though the British have left the city, its influence and legacy exists today through architecture and in more recent news, pro-democracy movements.

- Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

Bibliography

Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

Bickers, Robert and Isabella Jackson. Treaty Ports in Modern China: Law, Land and Power, edited by Bickers, Robert, Isabella Jackson. London: Routledge, 2016. doi:10.4324/9781315636856.

Cary Y. Liu. “Encountering the Dilemma of Change in the Architectural and Urban History of Shanghai.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 73, no. 1 (2014): 118-36. Accessed February 16, 2021. doi:10.1525/jsah.2014.73.1.118.

Gu, X, D Shang, B Peng, and X Li. “Structural Inspection and Analysis of Former British Consulate in Shanghai.” Structural Analysis of Historic Construction: Preserving Safety and Significance, 2008, 1537–43. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781439828229.ch179.

Images

Fig. 1: Former British Consulate-General Building (Elevation)

Group, SEEC Media. “Then and Now: Shanghai’s British Consulate Building from 1873.” Time Out Shanghai. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.timeoutshanghai.com/features/City_Life_/66808/Then-and-now-Shanghais-British-Consulate-Building-from-1873.html.

Fig. 2: The British Settlement, 1846

Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

Fig. 3: Chinese mapping of the old city and new settlement relationship, 1848

Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

Fig. 4: British Shanghai, 1855

Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

Fig. 5: British Survey Map of Shanghai, 1920

Balfour, Alan, and Zheng Shiling. Shanghai. Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 2002.

Fig. 6: First Floor Plan

Gu, X, D Shang, B Peng, and X Li. “Structural Inspection and Analysis of Former British Consulate in Shanghai.” Structural Analysis of Historic Construction: Preserving Safety and Significance, 2008, 1537–43. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781439828229.ch179.

Fig. 7: First Floor Plan (Poche)

Gu, X, D Shang, B Peng, and X Li. “Structural Inspection and Analysis of Former British Consulate in Shanghai.” Structural Analysis of Historic Construction: Preserving Safety and Significance, 2008, 1537–43. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781439828229.ch179.

Fig. 8: Former British Consulate-General Building (Elevation – Today) Group, SEEC Media. “Then and Now: Shanghai’s British Consulate Building from 1873.” Time Out Shanghai. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.timeoutshanghai.com/features/City_Life_/66808/Then-and-now-Shanghais-British-Consulate-Building-from-1873.html.