The Shakers were a religious utopian group that moved from Britain to America in the late 18th century. The Shakers originated in Manchester under the leadership of Ann Lee, who proclaimed herself the female incarnation of Christ.1 Delores Hayden describes in her book Seven American Utopias, that Ann Lee came to the religion after experiencing the death of multiple of her children in infancy or birth, and experienced “visions of an earthly paradise located far from the slums of Manchester and populated with angelic, sinless beings”.2 The Shakers viewed America as a blank slate for settlement, a worldview created by the narrative of white settler colonialism. The settlement and growth of Shaker communities as a utopian project grew out of a desire to reform and separate from the disorder of industrialization in Britain. In their effort to create Heaven on Earth, the Shakers used land acquisition, community layout, and building architecture as a form of religious expansion and control.

Land Acquisition and Settler Colonialism

As a utopian project, the Shakers operated within the framework of colonialism that was established by earlier European settlers who saw America as “terra nullius” or empty land that was available for the taking. In the century prior, settlers justified the dispossession of indigenous peoples lands by viewing themselves as a more enlightened population and used building and law to tame what they viewed as wilderness.3 Karl Joseph Hardy’s thesis titled “Unsettling Hope: Settler Colonialism and Utopianism” describes the constructed narrative from which colonizers operated, seeing “The New World”, as a blank slate to envision a “progressive and rational societal transformation aimed at redemption, salvation and transcendence”.4

Shakers saw land in America as an opportunity to manifest their own heaven on earth. In Julie Nicoletta’s paper titled “The Architecture of Control: Shaker Dwelling Houses and the Reform Movement in Early-Nineteenth-Century-America” she quotes historian Stephen J. Stein in his assertion that “the Shakers decision to leave Manchester resulted from their lack of success in spreading the faith in England. The American colonies, the Shakers believed, held more potential for attracting converts”.5 With the support of one wealthy follower, ‘Mother’ Ann Lee and eight others moved from the polluted urban sprawl of England in 1774, seeking clear rural land for the development of their own heaven on earth.6 They first settled in Albany, New York, with a communitarian vision of existing separate from the outside world. Their religious practice was centered on celibacy and confession, and they became known for their ecstatic form of dance worship, moving and dancing as their spirit guided them (hence the name ‘Shakers’).7

The Shakers saw new leadership over the course of their history and developed a set of religious laws that defined how they were to use land acquisition and building to grow their following. The act of building on land became one of the tangible ways of measuring a member’s religious commitment.8 Hancock Shaker Village in Massachusetts is an example of how the acquisition of land operated within a settler colonial framework. The land at Hancock village was donated by a wealthy farmer who was an original settler to the area, which was previously known as the Plantation of Jericho.9 The link between settler colonialism and the acquisition of land can be traced throughout many other Shaker settlements in America, with their land holdings totaling 10,000 acres in 1874.10 Delores Hayden describes in her book Seven American Utopias, the “land mania” that drove shaker communities, with land acquisition and cultivation being the driving force of their economy, occupying large plots of land in an effort to anticipate the further growth of their communities.11 Hayden states, “The physical process of designing and building new settlements was part of the communitarian goal and was fully integrated with the shaker religion. Members found in environmental design, the only activity broad enough in scope to accommodate their aspirations to turn the earth into heaven”.12

Community Organization and Millennial Law

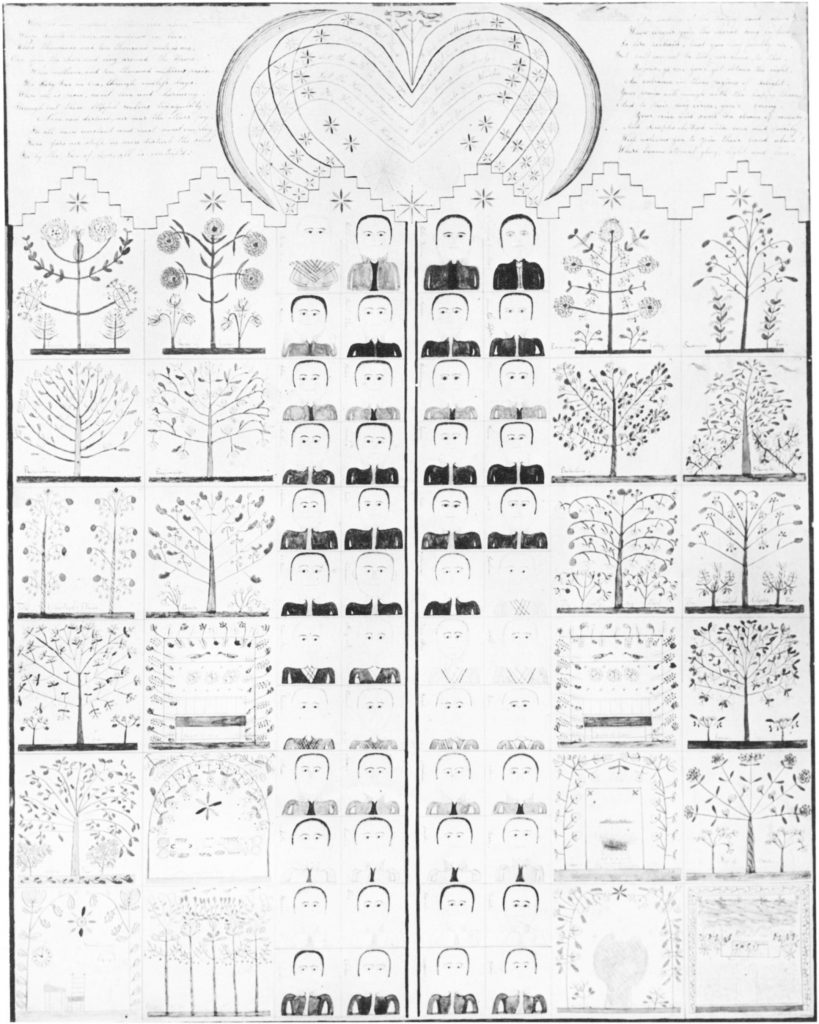

By 1826, nineteen permanent communities had been established and a set of Millennial Laws had been circulated by the central ministry.13 The Millennial Laws served as the guiding principles pertaining to all aspects of life but particularly to their ideas about how spaces should be built as a means of control and standardization between communities, and in relation to the outside world.14 Hancock Village was broken into groups of 30-100 individuals which they called ‘families’, and these groups were separated along a hierarchy of spiritual commitment.15 In every community, the most committed members were named the Church Family and lived at the center of the community near the office, store, schoolhouse and meetinghouse.16 The meetinghouse marked the pinnacle of the spiritual hierarchy, with the leaders living on the top floor in gender separated apartments.17 The other families were named geographically as North, South, East and West and were spread out from each other along the major roads of the community, all working in subservience to the greater communitarian goals.18

Hancock Village Meetinghouse Architectural Details

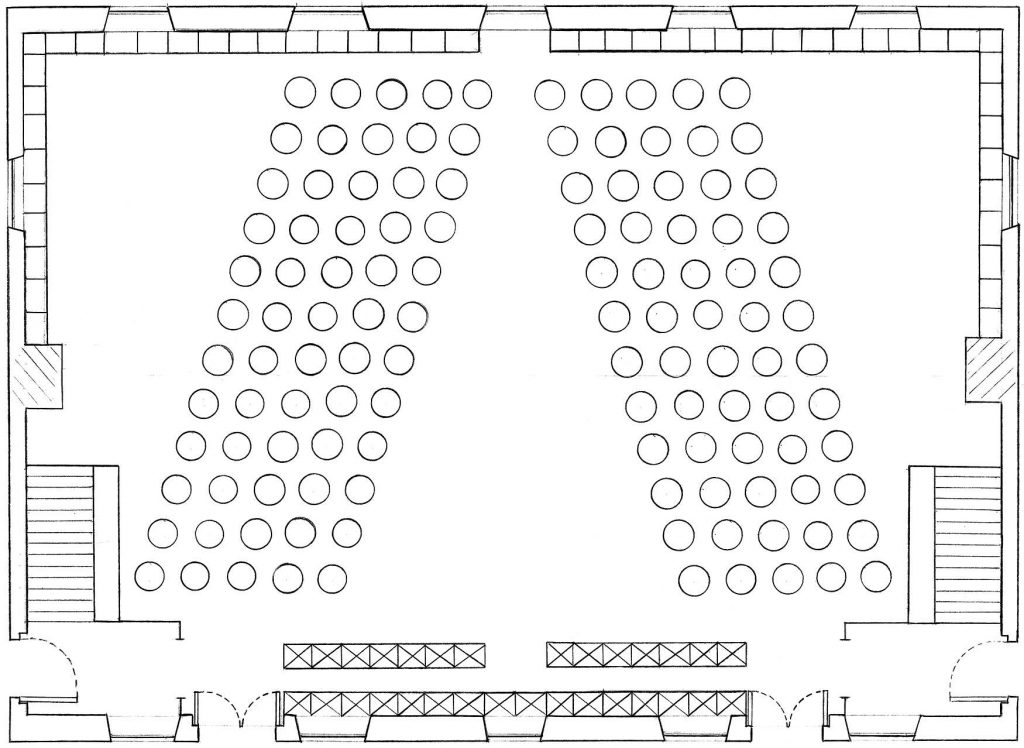

The central meetinghouse acted as a stage for the ritual practices of the Shakers. The Church Family meetinghouse at Hancock village is one example, demonstrating how the architecture was used as a device for controlling the movement of people and monitoring members’ religious commitment.19 The form of the building takes its cues from Dutch-American colonial architecture with a timber frame system and gambrel roof, which was a style that was present in the area since the Dutch colonized in 1609.20 The architect of the Church family meetinghouse at Hancock Village describes the structure as being “excessively framed”, using a timber system adapted to accommodate large spans which allowed members to move freely throughout the space during dance worship.21 The structure was built with 10”x15” oak posts at the corners of the room, windows and doors, and 10” x 6” white pine beams, spaced 4’-0” apart and spanning the entire width of the 30’x60’ space. Strong corbel braces were used to stiffen the connection between the horizontal plane and vertical posts.22 The beams and corbels that made up the structural system were boxed in and painted blue creating forcible lines on the ceiling as a mechanism of order and for controlling the organization of people.23

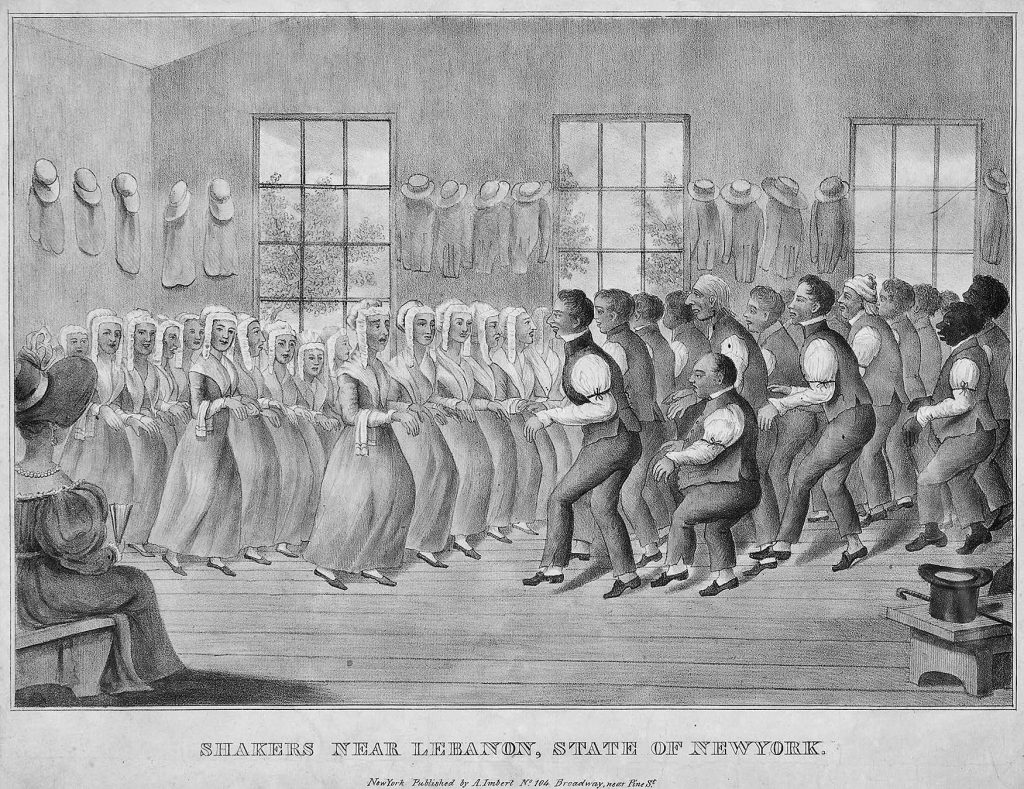

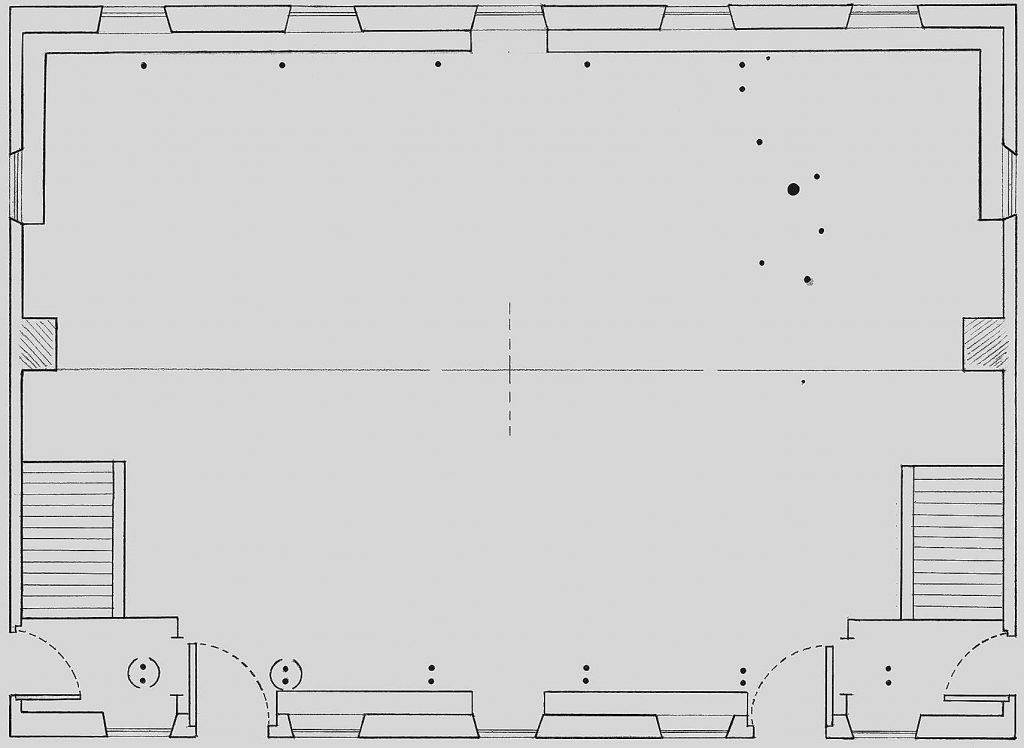

Similarly, the floor was a robust structure, designed to account for the significant live loads of people dancing. The wood planks were laid out with a clear seam line running gable to gable, which helped to delineate male and female sides of the room as members moved through the space in their dynamic worship.24 Variably sized wood and copper dance-floor cues were laid into the floor around the perimeter of the space, and several in a cluster in one corner of the room.25 These dance floor cues serve as an important mark of the architecture’s participation in controlling and standardizing the performative aspects of Shaker worship. While the ceiling beams guided the alignment of dancers from above, the cues in the floor oriented the dancers form below. Arthur McLendon in ” “Leap and Shout, Ye Living Building!”: Ritual Performance and Architectural Collaboration in Early Shaker Meetinghouses” describes the importance of the Shaker Sabbath performances, which were attended by large crowds of outside visitors and were critical in the outreach for potential converts.26 He goes on to eloquently describes the Shaker worship as a lively convergence of bodily rhythm and architecture and states:27

Visual rhythms of prominent ceiling joists, wide floorboards, and multiple rows of peg rail punctuated by large glowing window grids guided and encased worshippers in a sacral sphere of precise linearity. Animated bodily rhythms moved through the space with carefully coordinated stepping, turning, and bowing, all practiced to perfection and performed within the moving theology of Shaker dance with its ever-present gendered symmetry. (64)

Arthur E. McLendon. “‘Leap and Shout, Ye Living Building!’: Ritual Performance and Architectural Collaboration in Early Shaker Meetinghouses.” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 20, no. 2 (2013): https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048. 64.

Two sets of doors on the façade allowed separate gendered entry into the building, and to the circulation stairs that access the leadership apartments on the second floor. Windows were also used as an architectural element for surveillance within the interior of the meetinghouses. Shaker leaders used small interior windows that connected the main meeting space and the ministry’s quarters as a method of serveilling worship28.

Conclusion

All of these details, and many others, describe the ordered rhythm of Shaker architecture organized under Millennial Law to create a sense of control and hierarchy within Shaker culture. These guidelines acted as the instrument by which Shakers were able to achieve success and consistency in 19 villages across 5 states being America’s longest standing Utopian project.29 Their method of control over land and people were inextricably linked to white settler colonialism. The Shakers had a vision for creating heaven on earth, transforming all converts into reformed members of society and they used architecture as a means of spreading, and enforcing their religious rule.30 They occupied space and built successful communities by operating within a colonial framework which saw the new world as a blank slate for progressive societal transformation.

Endnotes

- Hayden, Delores. Seven American Utopias: The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism. Chapter 4 Heavenly and Earthly Space, 1790-1975. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1976. 65

- Hayden, 65

- Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. “Settler Colonialism as Structure: A Framework for Comparative Studies of U.S. Race and Gender Formation.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1, no. 1 (January 2015): 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649214560440.

- Hardy, Karl Joseph. 2015. “Unsettling Hope: Settler Colonialism and Utopianism.” PhD, Queen’s University. https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/handle/1974/13154/Hardy_Karl_J_06095600_PhD.pdf?sequence=1.

- Nicoletta, Julie. “The Architecture of Control: Shaker Dwelling Houses and the Reform Movement in Early-Nineteenth-Century America.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 62, no. 3, (Sept. 2003): https://doi.org/10.2307/3592519. 354

- Hayden, 65

- Hayden, 65

- Hayden, 68

- “Hancock, MA | The Berkshires – Discover the Berkshires.” Accessed Feb 16, 2021. https://discovertheberkshires.com/the-berkshires/hancock-ma.

- Hayden, 75

- Hayden, 75

- Hayden, 66

- Nicoletta, 355

- Nicoletta, 357

- Hayden, 92

- Nicoletta, 357

- Arthur E. McLendon. “‘Leap and Shout, Ye Living Building!’: Ritual Performance and Architectural Collaboration in Early Shaker Meetinghouses.” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 20, no. 2 (2013): https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048. 51.

- McLendon, 70

- McLendon, 49.

- “The Atlantic World: The Dutch in America, 1609-1664 / De Atlantische Wereld: De Nederlanders in Amerika, 1609-1664.” Accessed February 17, 2021. http://frontiers.loc.gov/intldl/awkbhtml/kb-1/kb-1.html.

- McLendon, 55

- McLendon, 55

- Hayden, 92

- McLendon, 56

- McLendon, 64

- McLendon, 64

- McLendon, 64

- Nicoletta, 362

- McLendon, 67

- Nicoletta, 352

Images

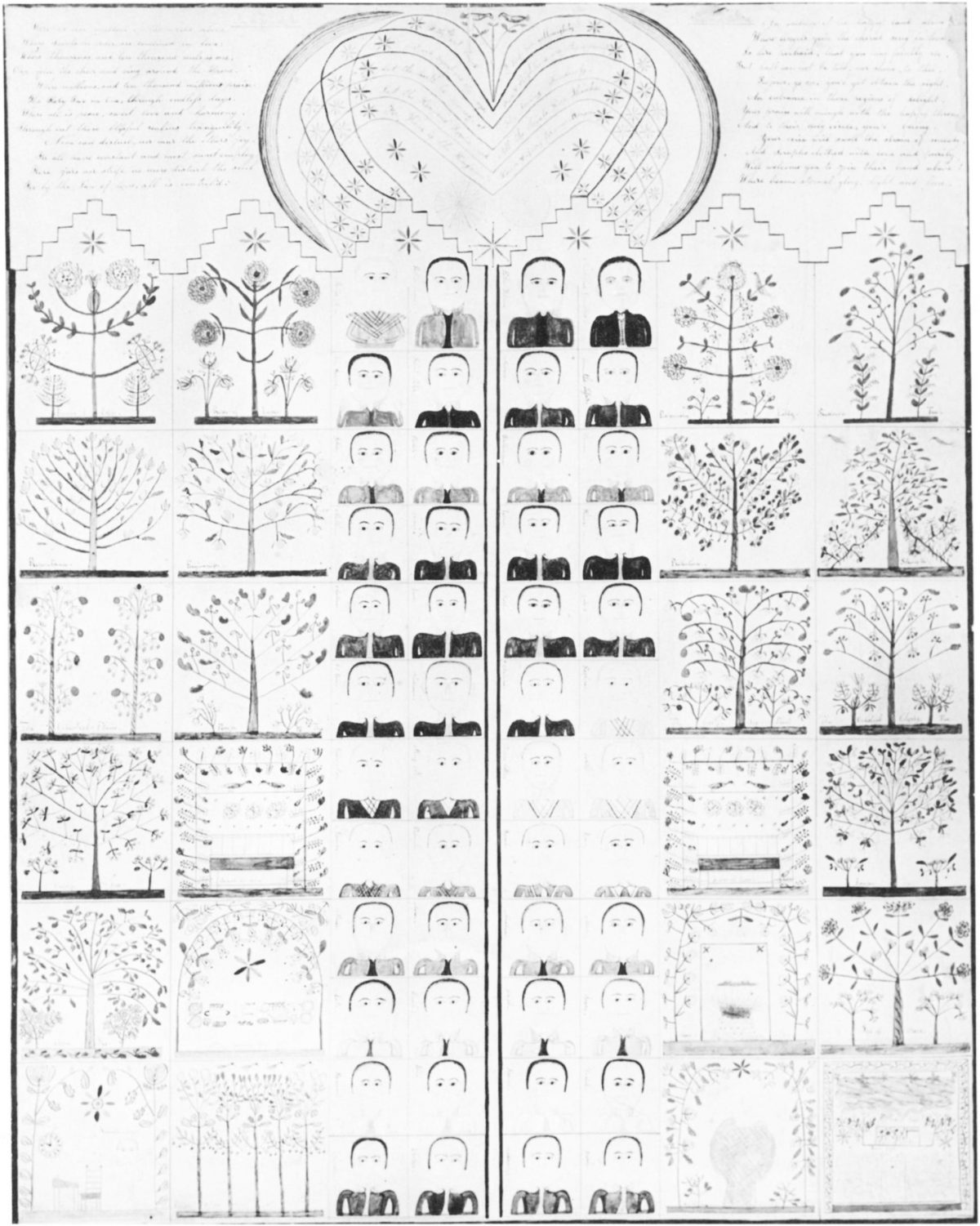

Fig. 1: Kitch, Sally L. “‘As a Sign That All May Understand’: Shaker Gift Drawings and Female Spiritual Power.” Winterthur Portfolio 24, no. 1 (April 1989): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1086/496397.

Fig. 2: Hayden, Delores. 1976. Site Plan, Hancock, in 1840, Showing Approximate Community Boundary. Seven American Utopias: The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism.

Fig. 3: Hayden, Delores. 1976. Church family, Hancock, aerial view from the direction of Mount Sinai. Seven American Utopias: The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism.

Fig. 4: McLendon, Arthur E. 2013. Shaker 1792 Meetinghouse, Hancock, Massachusetts. Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Vol. 20, No. 2. https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048

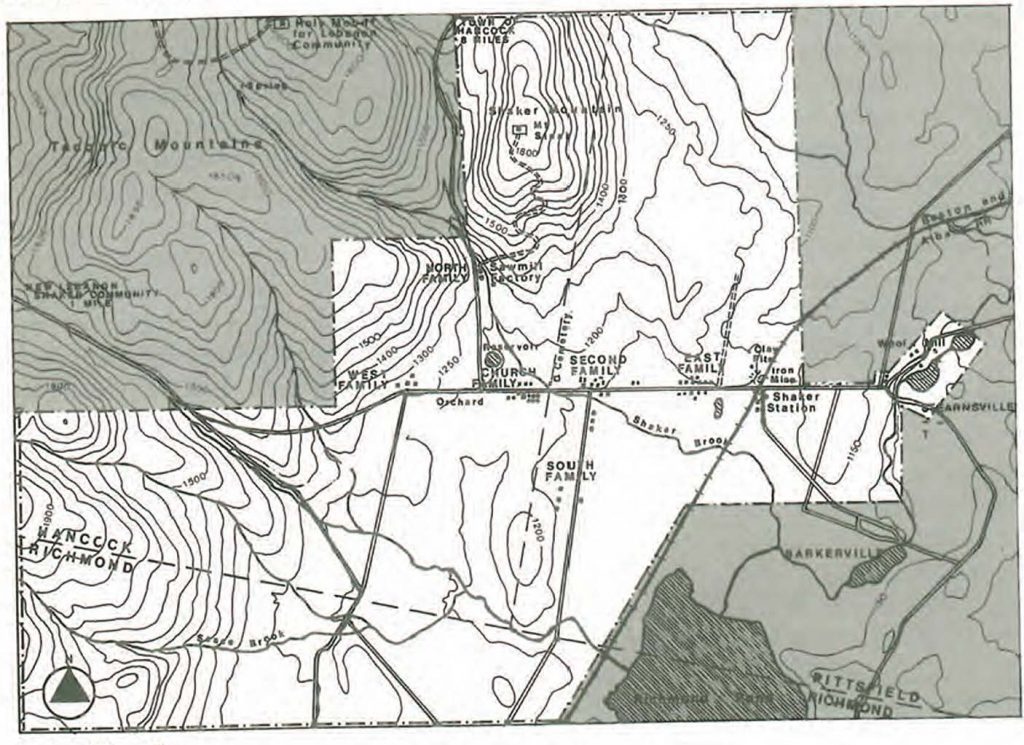

Fig. 5: McLendon, Arthur E. 2013. Anthony Imbert, Shakers Near Lebanon, State of New York, lithograph, c.1830s. Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Vol. 20, No. 2. https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048

Fig. 6: McLendon, Arthur E. 2013. Shaker 1792 Meetinghouse, Hancock, Massachusetts. Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Vol. 20, No. 2. https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048

Fig. 7: McLendon, Arthur E. 2013. Order of Shaker worship, c. 1800. Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Vol. 20, No. 2. https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048

Fig. 8: McLendon, Arthur E. 2013. Order of Shaker worship, c. 1800. Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Vol. 20, No. 2. https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048

Fig. 9: McLendon, Arthur E. 2013. Detail of Shaker dance-floor cues, 1972 meetinghouse. Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Vol. 20, No. 2. https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048

Bibliography

Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. “Settler Colonialism as Structure: A Framework for Comparative Studies of U.S. Race and Gender Formation.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1, no. 1 (January 2015): 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649214560440.

Hardy, Karl Joseph. 2015. “Unsettling Hope: Settler Colonialism and Utopianism.” PhD, Queen’s University. 1-268 https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/handle/1974/13154/Hardy_Karl_J_06095600_PhD.pdf?sequence=1.

Hayden, Delores. Seven American Utopias: The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism. Chapter 4 Heavenly and Earthly Space, 1790-1975. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1976. 65-103

“Hancock, MA | The Berkshires – Discover the Berkshires.” Accessed Feb 16, 2021. https://discovertheberkshires.com/the-berkshires/hancock-ma.

Kitch, Sally L. “‘As a Sign That All May Understand’: Shaker Gift Drawings and Female Spiritual Power.” Winterthur Portfolio 24, no. 1 (April 1989): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1086/496397.

McLendon, Arthur E. “‘Leap and Shout, Ye Living Building!’: Ritual Performance and Architectural Collaboration in Early Shaker Meetinghouses.” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 20, no. 2 (2013): https://doi.org/10.5749/buildland.20.2.0048. 48-76

Nicoletta, Julie. “The Architecture of Control: Shaker Dwelling Houses and the Reform Movement in Early-Nineteenth-Century America.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 62, no. 3, (Sept. 2003): pp. 352–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/3592519. 354

“The Atlantic World: The Dutch in America, 1609-1664 / De Atlantische Wereld: De Nederlanders in Amerika, 1609-1664.” Accessed February 17, 2021. http://frontiers.loc.gov/intldl/awkbhtml/kb-1/kb-1.html.