The Paris Opera House was designed and completed by Charles Garnier between 1861 and 1875.[1] Dripping in opulence and grandeur, ‘Palais Garnier’ is the quintessential depiction of France’s Imperial Power acquired during the Second Empire rule; representing the growing bourgeoisie population, Napoleon III’s political ambitions both domestically and internationally, and a legacy of symbology which transgressed into colonized regions. This entry will be looking at the Opera House through its socio-political context, its economic funding in relation to colonialism, and its legacy as a symbol of French Imperial Power.

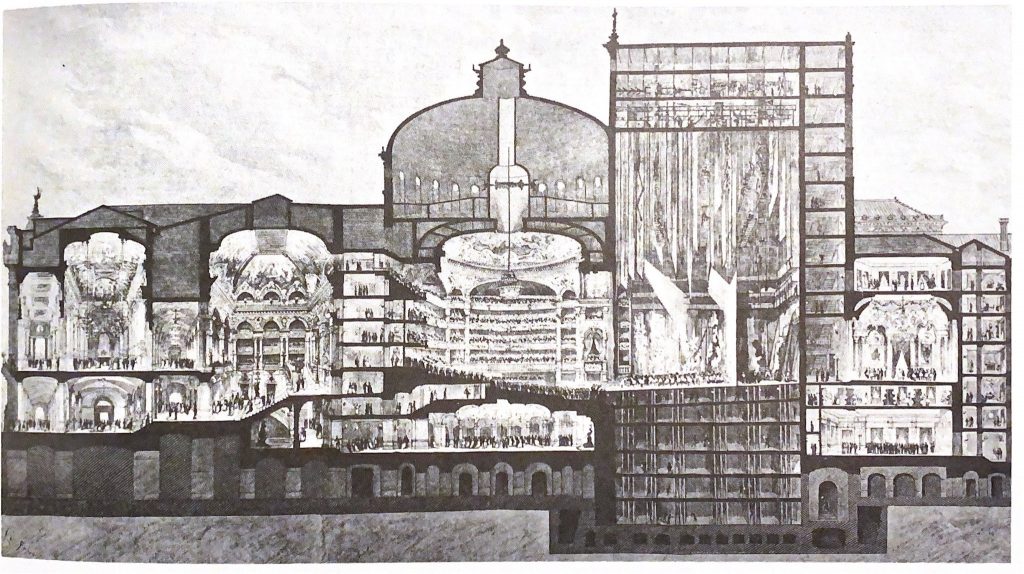

This section highlights the procession of spaces as a bourgeois ritual of Opera. The interior spaces are as opulent as the exterior.

[1] Mead, Christopher. “Urban Contingency and the Problem of Representation in Second Empire Paris.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 54, no. 2 (1995): 138

Second Empire & The Paris Renovation

France went through significant shift throughout the 19th century witnessing the triumphs and failures of multiple republics, empires, and monarchies. The Second Empire, ruled by Napoleon III, the first President and last Monarch of France, would see to the most significant changes to France including the renovation of Paris. Drafting a new plan for Paris, President Louis-Napoléon signed a law in 1852 allowing the government to expropriate properties in way of rebuilding the city and its streets. This gave the government authority to expedite urban renewal while still “remaining a collaborative venture between public and private interests.”[1]

The following year Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann was commissioned to begin the first phase of Paris’ rebuild lasting 1853-1870.[2] The rebuilding of Paris sought myriad outcomes beyond the sanitization and beautification of a polluted medieval city. It included protecting the government during civil unrest by widening the streets so barricades would be impossible and creating shorter routes between the barracks and lower class working districts.[3] This was an effort on Napoleon III to maintain control over the Population of Paris, specifically the lower class in workers’ districts.

Under the reign of Napoleon III, the population of Paris doubled.[4] Many of the bourgeoisie who moved from the city to the suburbs to escape its pollution came flocking back. With this new population the older affordable housing was demolished and the lower class was displaced “into the city’s remaining and increasingly expensive slums.”[5] “The breaking up of whole social neighborhoods by Hausmann’s works, forcing the poor into even more crowded quarters while applying the elegant veneer of civilization to the boulevard facades [for the bourgeoisie.]”[6] This dispossession of land from the lower class was the beginning of Napoleon III’s vision of Imperial Power and grandeur for Paris.

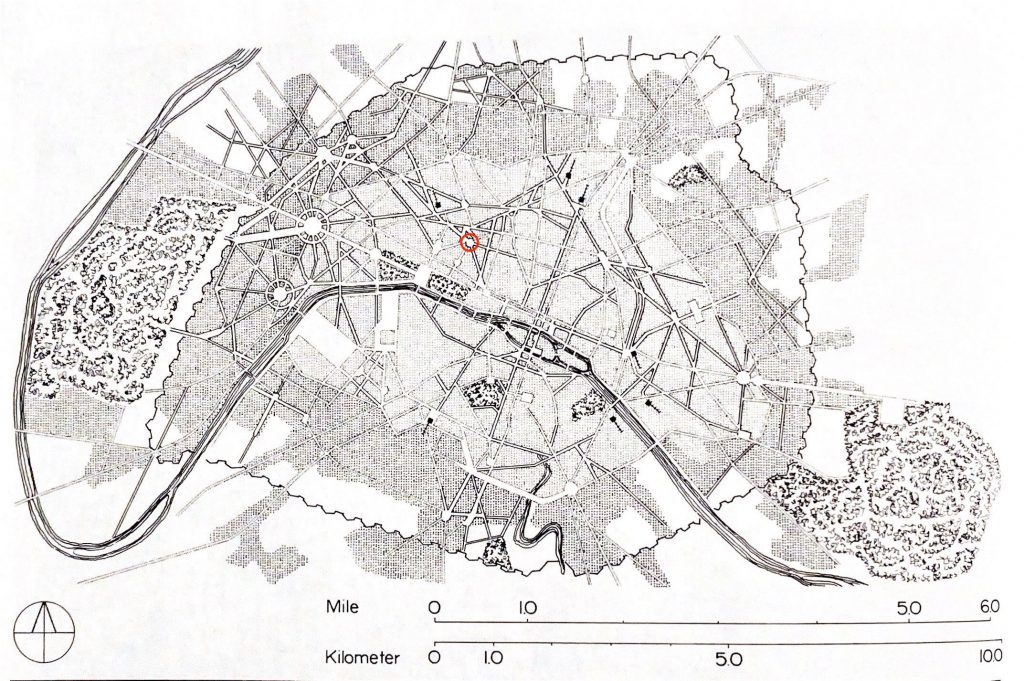

These new Boulevards were designed to be deep elongated corridors with uninterrupted arteries.[7] Each would be lined with rhythmic structures in the quintessential Second Empire style, with its tripartite design of a commercial base, pilastered upper levels, and mansard roof (or attic space). Majority of these new Boulevards terminate at a civic space, monument or building. Circulation of Paris now revolved around the Second Empire’s symbols of authority and power. Although these buildings were intended for the intellectual bourgeoisie interested in politics, some argue that “the interest of the French government in the 1850s and 1860s became one of distracting precisely that public from participating in politics. In lieu of political power, Napoleon offered them a magnificent playground.”[8] This outlines that Napoleon III’s intentions to renovate Paris were insidious and a way to distract the public from government affairs.

The site of Garnier’s Opera is highlighted with a red circle. Proposed new streets are marked in a thick black line and cross hatched areas represent new districts. The intervention is striking when you zoom out at birds eye view.

[1] Mead, Second Empire Paris., 149

[2] Mead, Second Empire Paris., 138

[3] Benjamin, Walter. “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century” (Exposé of 1935). The Arcades Project. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1999., 12

[4] James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. Architecture since 1400. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014., 273

[5] James-Chakraborty, Architecture since 1400., 281

[6] Vidler, Anthony. “The New Industrial World: The Reconstruction of Urban Utopia in Late Nineteenth Century France.” Perspecta 13/14 (1971): 253

[7] Walter, Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century., 11

[8] James-Chakraborty, Architecture since 1400., 278

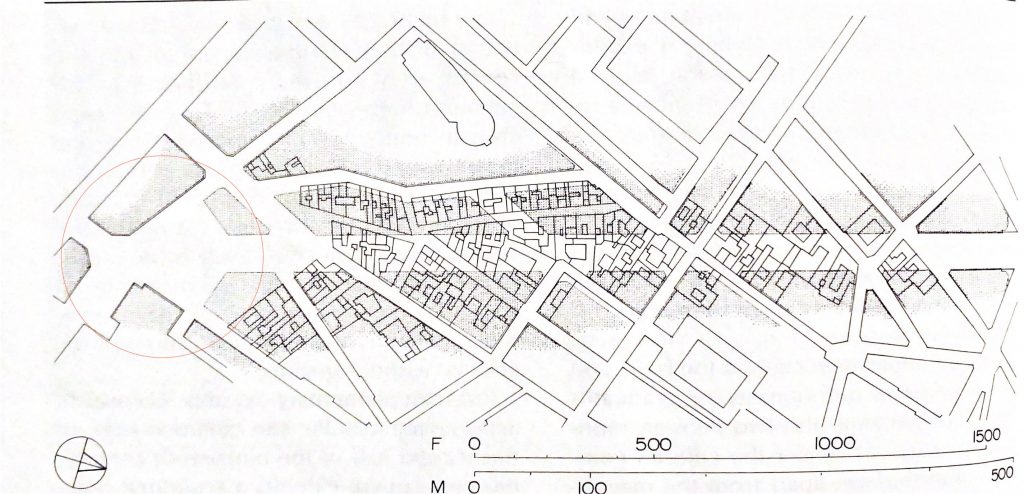

The site of Garnier’s Opera is highlighted with a red circle. Thicker black lines indicate new road boundaries. The more zoomed in look starts to give a scale of the mass destruction that occurred.

The Paris Opera House

In 1860, Napoleon III declared Paris needed a new Opera so the state held a design competition. Charles Garnier won the competition and was commissioned to design the Opera in June of 1861.[1] Some suggest that the Opera was a natural progression for the city, such as journalist Ernest Chesneau in 1875: “for the enlarged, aerated, sanitized Paris, transformed with the clearest foresight of social needs and at the same time with magnificence by the imperial government.. one needed an Opera house that was worthy of the grandeur, the luxury, and the arts of the new Paris.”[2] The siting of the Opera was contested for almost a century until Hausmann and Napoleon III decided on its final location in c.1860.[3] Confined at the end of Avenue de l’Opera, the Opera house would be constructed in proximity to glamourous department stores, and have a direct connection to the Louvre.[4] The view of the terminated axis is a striking Neo-Baroque styled Opera that is both dripping in opulence and the indoctrination of France’s Imperial Power.

The Opera’s style built upon the new the French national style, one that coopted the classical styles of antiquity from Greece and Rome[5] and culminated in Claude Perrault’s east façade of the Louvre. The design of its exterior borrows from Classical Palladian models, Italian Renaissance, and Beaux-Arts to create a uniquely eclectic style. Garnier suggests that the style is “du Napoleon III.”[6] The construction occurred when the archetypal Parisian style was being used for both public and private structures, leading to the design of complimentary surrounding residential buildings.[7] The image of imperial civic structures bleeds into the typical style of Paris, emulating the Second Empire’s Imperial Power throughout the city.

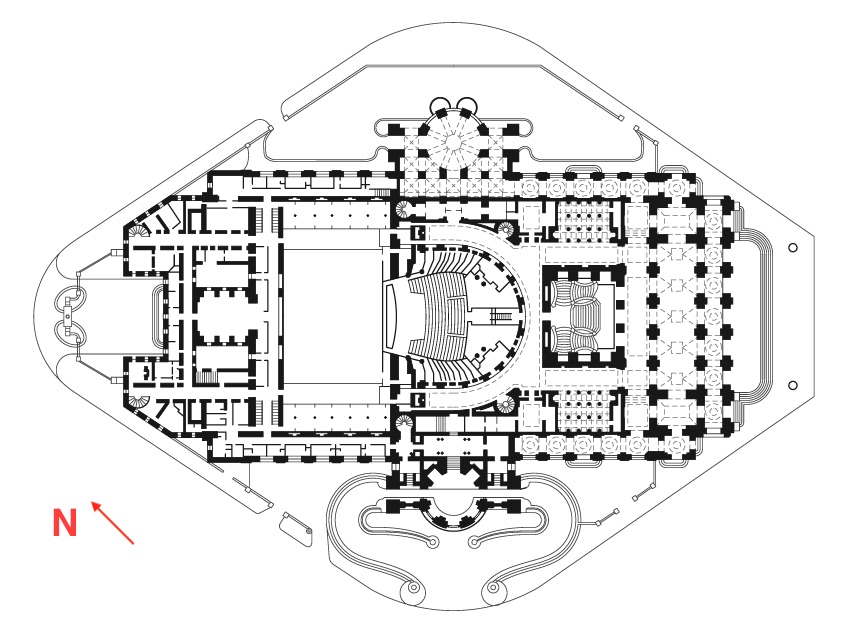

Garnier pays homage to his Beaux-Arts education with this horizontal plan with particular attention to the procession of Opera goers through circulation. He designs each space as separate volumes and provides almost enough backstage space as he does to the front of house.

No expense was spared on the building’s ornamental stone work, opulent sculptural busts and statues, and copper and gold finishes. Its placement on a polygonal site at the end of multiple intersections would promote views to the building, be more secure for Napoleon III, and hamper the spread of fires.[8] Its plan, although predominantly rectilinear on a polygonal site, was remedied by flanked “curved buildings whose courtyards could serve as imperial public carriage entrances” as well as curving the surrounding buildings, and widening Avenue de l’Opera beyond its initial 22 metre width.[9] This created a nexus around the Opera house symbolizing Second Empire Paris, and further iterating France’s Imperial Power.

The Opera’s interior is as opulent as the exterior. The plan reflects Garnier’s Beaux-Arts training at the Ecole in the practical matters of “circulation and clear expression of functions through separate volumes.”[10] The procession of spaces was not focused on the Opera itself, but also the entrances which shepherded patrons through opulent waiting areas for pre-and-post-show socialization.[11] “Seeing and being seen were essential components of the performance; the ceremonial space in front and support space behind exceed the volume of stage and auditorium. The monumental staircase, up which all theatregoers ascended to their seats, replaced the imperial court as the center of socially ambitious Paris.”[12] The Opera acts to mix the rituals of bourgeoisie society within the civic structures of Imperial France. With so much opulence, grandeur, and money on display, it poses the question: who is financing this project?

Garnier’s grand staircase be a vital component of the opera ritual. All theatre goers would have to take these stairs to their seats. It was meant to yourself off to the rest of the bourgeois society. The interior is more opulent than the exterior with almost every finish being dressed with an ornamental carving.

[1] Mead, Second Empire Paris., 138

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 142

[4] James-Chakraborty, Architecture since 1400., 285

[5] Sara Stevens, “Constructing The Past,” ARCH 504: Empire Building (class lecture, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, January 14, 2021).

[6] Mead, Second Empire Paris., 138

[7] Mead, Second Empire Paris, 139

[8] James-Chakraborty, Architecture since 1400., 285

[9] Mead, Second Empire Paris, 155

[10] Kostof, Spiro and Greg Castillo. A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995., 644

[11] Kostof. Settings and Rituals., 643

[12] James-Chakraborty, Architecture since 1400., 286

Finances, Colonization, and the Opera’s Legacy

In Christopher Mead’s book Charles Garnier’s Paris Opera: Architectural Empathy and the Renaissance of French Classicism, he argues that the client of the Opera was both Napoleon III with his private allowance, and the voting public with their tax dollars.[1] The government’s money isn’t solely from the state’s tax payers; it would also encompass the country’s wealth from trade and resource extraction.

Nineteenth century France rebuilt its colonial empire from no colonies in 1810 to the second most prominent Imperial Power on the colonial stage by the 20th century.[2] The second colonial empire was marked by the invasion of Algiers in 1830,[3] followed by expansive takeover in the coming decades resulting in a genocide of countless Algerians. The 1840s saw further expansion of French influence with occupation of Mayotte and Nosy Be (islands off the coast of Madagascar), the Marquise Islands and Tahiti in the Indian Ocean, and New Caledonia off the coast of Australia.[4] This highlights France’s expansion into new territory during the Second Empire. This laid the groundwork for future colonization and resource extraction. In fact, between 1787 and 1879, France’s African colonies steadily increased their exports. French exports from Sub-Saharan Africa (south of the Sahara desert) totalled 0.1% of France’s exports in 1787 to 0.5% in 1879. More so, North Africa’s exports increased from 0.5% to 4.5% and accounted for 2.5% of French Imports.[5] Though these numbers are not staggeringly high, capital was gained by these colonies. This money, in turn was given back to the French government and would have in part paid for the construction of the Paris Opera House.

Colonialism by the French used assimilation tactics to integrate their culture into colonies through infrastructure, architecture, and cultural practice. This was pronounced in France’s Indochinese colonies (Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam), taking form in the destruction of historical buildings and replacing them with French styled civic structures such as museums and operas.[6] These actions taken by French colonists sought to erode the existing culture of its colony and assimilate the them with French traditions. It highlights their assumption of their cultural practices being more superior.

One individual colony directly relates back to Paris and the monumental power envisaged through the Second Empire. At the end of the 19th century in Hanoi, it was decided that a French style Opera was needed and construction began in 1901. These constructions were considered a more intrusive stage of colonization.[7] For the French, the Opera was an “expression of [their] communal values and prestige” and was “to proclaim the superiority of their culture as well as to demonstrate their allegiance to a distant home.”[8] This was thought to be completed through technological advancement and craftsmanship of their architecture.

The design of the Opera changed over its decade of construction but the completed building was akin to the Paris Opera house in architectural form, siting, and development of neighbouring roads and buildings. “The physical presence of theater buildings in combination with the less tangible performances of Opera within embodied the glorious past of the metropole and the triumphant future of the empire.”[9] Colonists developed Hanoi in the style of a contemporary western city which ended up drawing parallels between Paris and Hanoi. These comparisons portrayed Hanoi as the colonial equivalent of Paris.[10] The action of constructing a civic building comparable to that of Paris’ Opera codifies the Imperial Power of France in its colonized regions and postulates the legacy of the Paris Opera in a very tangible way.

Opened in 1911, the Hanoi Opera House shares many of the architectural components from the Paris Opera House. The most prominent resemblance is the main entrance where both share a similar arcaded base, recessed covered upper floors and two symmetrical cupolas. The Hanoi Opera also maintains a similar central dome structure and protruding entries from the sides.

[1] Taylor, Katherine Fischer. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 53, no. 2 (1994): 242

[2] Clément, Alain. “French Economic Liberalism and the Colonial Issue at the Beginning of the Second Empire (1830-1870).” History of Economic Ideas 21, no. 1 (2013): 48; Thomas, Martin, and Andrew Thompson. “Empire and Globalisation: from ‘High Imperialism’ to Decolonisation.” The International History Review 36, no. 1 (2014): 144

[3] Clément, French Economic Liberalism., 49, 52

[4] Ibid., 52-3

[5] Ibid., 54

[6] Aldrich, Robert. “Imperial Mise En Valeur and Mise En Scène: Recent Works on French Colonialism.” The Historical Journal 45, no. 4 (2002): 923, 927; McClellan, Michael. “Performing Empire: Opera in Colonial Hanoi,” Journal of Musicological Research, 22:1-2, (2003): 135

[7] McClellan, Opera in Colonial Hanoi., 147-148

[8] Ibid., 137

[9] Ibid., 142

[10] Ibid., 154-155

Conclusion

The socio-political context of France under the Second Empire rule is essential in understanding the reasons and events leading up to the construction of Garnier’s Opera. Napoleon III’s political ambitions for the city, country and their international affairs would intend to protect his fascist rule through the Paris Renovation, new civic structures, and colonial domination. Garnier’s Opera, exuding luxury and superior culture, would become the major beacon in Napoleon III and Haussmann’s newly renovated Paris; acting as a prototypical symbol for the Second Empire’s Imperial Power.

Bibliography

Urban Contingency and the Problem of Representation in Second Empire Paris

Aldrich, Robert. “Imperial Mise En Valeur and Mise En Scène: Recent Works on French Colonialism.” The Historical Journal 45, no. 4 (2002): 917-36.

Benjamin, Walter. “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century” (Exposé of 1935). The Arcades Project. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1999.

Clément, Alain. “French Economic Liberalism and the Colonial Issue at the Beginning of the Second Empire (1830-1870).” History of Economic Ideas 21, no. 1 (2013): 47-75.

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. Architecture since 1400. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Kostof, Spiro and Greg Castillo. A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

McClellan, Michael. “Performing Empire: Opera in Colonial Hanoi,” Journal of Musicological Research, 22:1-2, (2003): 135-166.

Mead, Christopher. “Urban Contingency and the Problem of Representation in Second Empire Paris.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 54, no. 2 (1995): 138-74.

Leon, Pevsner Nikolaus Bernhard. “A History of Building Types,” Princeton University Press, 1979.

Stevens, Sara. “Constructing The Past.” ARCH 504: Empire Building. Class lecture at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, January 14, 2021.

Summerson, John. “Classical Language of Architecture: with 139 Illustrations,” Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1980.

Taylor, Katherine Fischer. “Designing Paris: The Architecture of Duban, Labrouste, Duc, and Vaudoyer by David van Zanten: Charles Garnier’s Paris Opéra: Architectural Empathy and the Renaissance of French Classicism by Christopher Curtis Mead.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 53, no. 2 (1994): 239-42.

Thomas, Martin, and Andrew Thompson. “Empire and Globalisation: from ‘High Imperialism’ to Decolonisation.” The International History Review 36, no. 1 (2014): 142-170.

Vidler, Anthony. “The New Industrial World: The Reconstruction of Urban Utopia in Late Nineteenth Century France.” Perspecta 13/14 (1971): 243-56.

Illustration Credits

Cover Photo: James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. Architecture since 1400. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014., 286, fig. 18.9

Figure 1: Leon, Pevsner Nikolaus Bernhard. “A History of Building Types,” Princeton University Press, 1979., 85, fig. 6.69

Figure 2: Kostof, Spiro and Greg Castillo. A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995., 644, fig.25.10a

Figure 3: Kostof, Spiro and Greg Castillo. A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995., 644, fig.25.10b

Figure 4: James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. Architecture since 1400. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014., 287, fig. 18.10

Figure 5: James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. Architecture since 1400. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014., 288, fig. 18.11

Figure 6: John W Banagan, Getty Images: https://lp-cms-production.imgix.net/2019-06/5fd1918ae3e4f1bac57a3ed3b3306102-hanoi-opera-house.jpg