The convoluted emergence of the federal center of American democracy and how it reflects the colonial roots of a nation

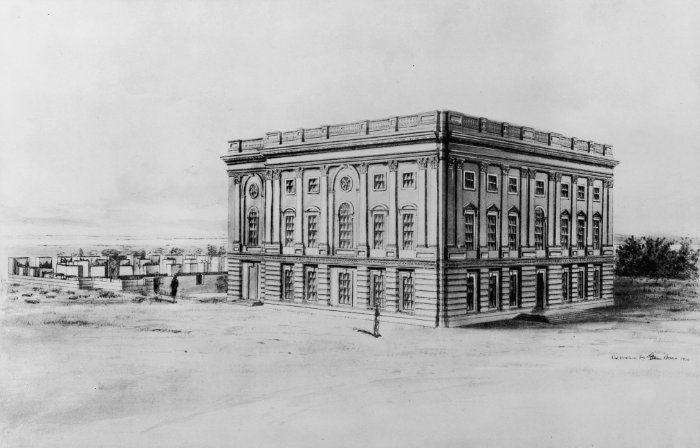

The location and architecture for the U.S federal government did not always exist as it does today. The immediate image that is conjured up of the white, neoclassical portico and columns in front of a large dome is only the current status of what is known as the U.S Capitol. Just like the society it was created to represent, this architecture has changed and evolved since the country was conceived in 1776. The capital of the country was also not always in Washington D.C, and prior to 1800 had been located in several northeastern cities of the United States, including New York City and Philadelphia1. The move was made to a still under construction U.S Capitol building in Washington D.C in the year 1800 (see Figure 1, above). The development of the U.S Capitol at this site and period in history is able to demonstrate how the forces of colonization, slavery, commerce and globalization acted upon the country. This architecture will serve as the conduit between all of these forces, showing how early key figures, influences and choices shaped this building into becoming foundational to the American democracy that it continues to represent. The convoluted path that that this architecture took in being designed and constructed in the early 19th century will be used to provide insight to the complex and contradictory nature that slavery operated within at the time and how the ideas established during this tempestuous period of history went on to be vital to the American identity.

Thomas Jefferson

The early establishment of an architecture made to represent the values of the fledging U.S and their government came from one of their founding fathers and the third U.S President Thomas Jefferson. In the same year that Jefferson had first drafted the American Constitution in 1776, he had also drafted plans for the Capitol building of the state of Virginia. He designed this building in a Neoclassical style that he intended to serve as a model for the designs of other state capitols as well as that of the future federal capitol.2 His logic with the design of the Virginia state capitol, and general approach to American civic architecture, was to use neoclassical forms to represent the American Enlightenment period, implying American as a type of succession from Greco-Roman civilizations. But Jefferson’s goal of signifying the liberty of the American people through this style of architecture soon became problematic, long before the federal capitol building in Washington D.C was designed. This can be seen more clearly when the building plans for the Virginia capitol building are put next to the Constitution, both drafted by the same man in the same year. From this constitution came the phrase “all men are created equal”3, which at first appears very congruous with the revival of architecture taken from the philosophic and Humanist Ancient Greece. This becomes complicated when the role of slavery in the formation of America is considered. The widespread prevalence of slavery in the U.S at this time undeniably contradicts Jefferson’s statement in the Constitution since he had also stated that “the people did not include Negroes”4.

Slaves in America were considered chattel, but played an integral role in the economy at the time and the formation of a new, white, American culture. Jefferson himself grew up with slaves at the Tuckahoe plantation in Virginia and later lived on his own plantation, Monticello. Jefferson’s design of Monticello (built in 1772) also leaned heavily into a neoclassical style, emulating Palladio and serving as an even earlier architectural reference that would later inform American civic architecture. Jefferson himself owned up to 200 slaves at one time, and over 600 throughout his lifetime. He freed a total of only two of those slaves while he was alive, with another five being freed upon his death in 1826. These facts implicate Jefferson, the individual largely responsible for the creation of American civic architecture, and complicates the identity of the American people from the very start. Jefferson was even aware of the societal divide that slavery could create, citing that:

“deep rooted prejudices entertained by whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they sustained.” Emancipation and citizenship for freed blacks could only result in “convulsions which will probably end but in the extermination of one or the other race.” A civilization, therefore, could not thrive with a free black population. The undesirability of blackness, the “unfortunate difference of color, and perhaps faculty, is a powerful obstacle to emancipation of their people”. 5

Washington D.C & William Thornton

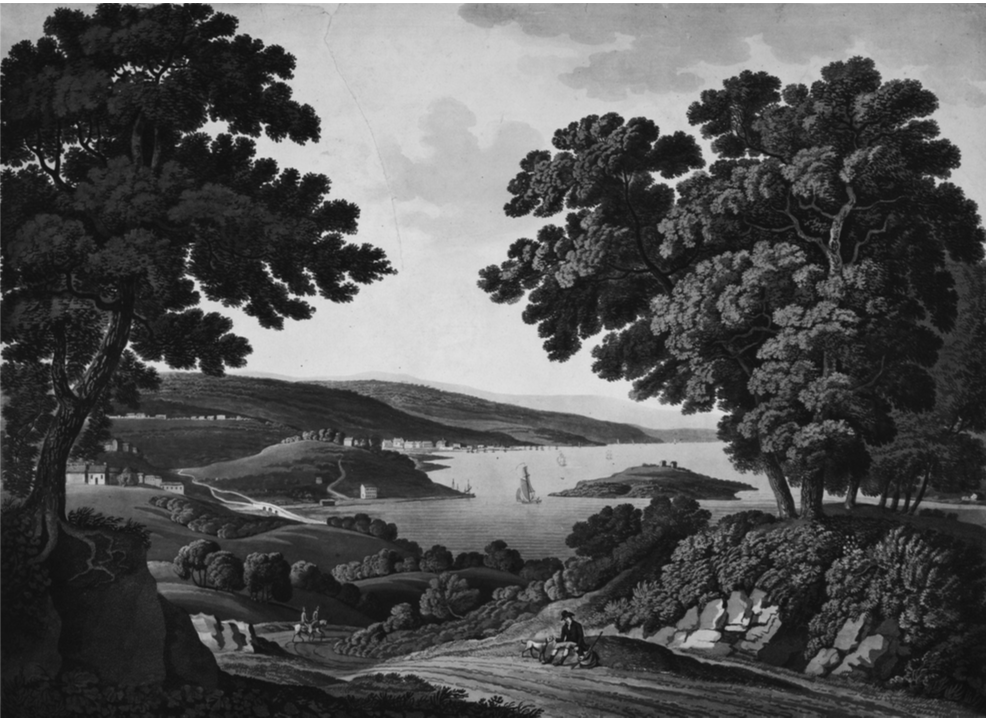

In 1792, Thomas Jefferson was the secretary of state for the first U.S President George Washington. They had put in motion a plan to move the country’s capital from Philadelphia to a 10-square mile area on the Potomac River. This land had been dispossessed from American Indigenous groups and was currently a mixture of marshy wetland and converted farmland. It occurred on the American state border of Maryland and Virginia, with both respective states providing loans to keep the capitol at that location. It was renamed after Washington, who reveled in the idea of constructing a new capitol city. The marshy wetland was renamed the Tiber River6, one of many obvious references to Roman culture. In addition to the neoclassical use of ancient Roman building style and renaming their river after that which runs through Rome, the hill that the capitol building was to be situated upon, was also swiftly changed from Jenkins Hill to Capitol Hill in reference to Capitoline Hill of Ancient Rome.7

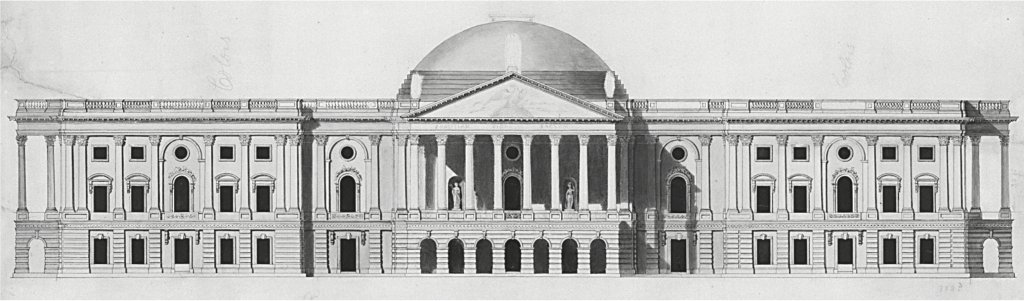

A design competition was held in the spring in 1792 but both Jefferson and Washington were disappointed with the results.8 The eventual winner, English-born William Thornton, submitted his proposal months after the deadline since he had drafted his plan for the U.S Capitol from his family’s plantation in Torola of the British Virgin Islands and then travelled to Philadelphia upon its completion. Thornton was a slaveholding abolitionist, doctor and amateur architect who was deeply entrenched in networks of the Atlantic world. He had inherited between 70 and 80 slaves from his family plantation, and although Thornton spoke for the emancipation of slaves, including those under his own control, his plantation operated with the slaves were considered “free tenants for life”9. This statement also appears quite contradictory, as Thornton could remove all of their rights to property and freedom that he provided if they attempted to leave the plantation or refuse obligatory work.

Construction

Thornton’s design for the U.S Capitol exemplified the neoclassical tendencies that had been fancied by Jefferson which was becoming the architecture of the American Enlightenment. Similar to Jefferson, Thornton’s architecture was haunted by the racialized other10 that played a large role in construction. The construction of the U.S Capitol, just like the previous Virginia state capitol, was constructed by slaves in more ways than one. Slaves were enlisted as laborers and skilled craftsman for the construction of the physical building. The wealth produced by slaves on plantations around the U.S also funded the creation of the building, since slave-run operations still were a major part of the economy. In doing both, slaves have also played a large role in manufacturing the political identity of the country, by erecting the neoclassical columns and triangular pediments which had come to represent the power of the governing class of white American men. (p.43) The slaves that were brought from the surrounding farms and even surrounding states helped establish the most important public building in the nation that had enslaved them.

The construction of the U.S Capitol and Washington D.C in general around the turn of the century was described by Henry Letrobe (architect of U.S Capitol in early 1800’s) as being “badly planned and conducted”11. And on top of that, Thornton’s original design was largely ill-conceived and had many deficiencies. These were identified by supervising architects like Henry Letrobe, an English-born and trained architect who worked on the Capitol in the early years. The original design was expensive to build, the columns were spread much further apart than they could be constructed, the staircases lacked sufficient headroom, important rooms lacked sufficient light, and the list goes on12. This has resulted in the conglomeration of many different architects playing a role in the design of the Capitol building as it evolved over the years.

Impact

The architecture of the U.S Capitol has grown and changed with the country that it was made to represent. It has gone through almost continual renovations and restorations in the 221 years since it was first inhabited by the nation’s government. From addition of a larger cast iron dome to replace the original wooden-framed one in the mid 19th century, to the most recent addition of a massive U.S Capitol Visitor Center which is fully submerged within the earth surrounding the main building, the infrastructure of the U.S government is continually changing, just as policies and law are introduced and terminated with the times. But the legacy of the U.S Capitol building is much more complicated given the history that it was originally created within. The violence of colonialism and slavery have been intrinsically linked with the establishment of the American culture narratives, which were made to embody freedom, liberty and progress. The contradiction of values and practices, and the purporting of equality during the era of initial construction of the U.S Capitol set the entire nation on a metaphorically unstable foundation that is still very much being grappled with today. Going all the way back to Jefferson’s adoption of a neoclassical style in the late 18th century, a national identity surrounded the particular style, and an identity which was exclusively for the white upperclassmen that participated in the democracy at the time. This style, first seen at Monticello, went on to impact the designs of other plantations in the American south. The co-opting of this historical style by early American has now evolved into something else entirely, and rewritten its own values that speak to power and whiteness. And with this same government building representing Americans today, it has developed into a less universal symbol of freedom, given the different histories that its citizens have experienced throughout the U.S Capitol’s existence.

Notes

- Robert Fortenbaugh, “Nine Capitals of the United States,” United States Senate, 1948.

- Mabel O. Wilson, “Notes on the Virginia Capitol Nation, Race and Slavery in Jefferson’s America.” In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, ed. by Irene Cheng, Charles Davis, 23.

- Wilson, “Notes on the Virginia Capitol Nation,” 26.

- Wilson, “Notes on the Virginia Capitol Nation,” 42.

- Wilson, “Notes on the Virginia Capitol Nation,” 40.

- Jean H. Baker, “Capital Projects.” In Building America: The Life of Benjamin Henry Latrobe (Oxford Scholarship Online, 2019), 72.

- Baker, “Capital Projects,” 74.

- Peter Minosh, “American Architecture in the Black Atlantic William Thornton’s Design for the United States Capitol” In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, ed. by Irene Cheng, Charles Davis, Mabel O. Wilson, 51.

- Minosh, “American Architecture in the Black Atlantic,” 47.

- Minosh, “American Architecture in the Black Atlantic,” 56.

- Baker, “Capital Projects,” 72.

Bibliography

Baker, Jean H. “Capital Projects.” In Building America: The Life of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 72-109. Oxford Scholarship Online, 2019.https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/view/10.1093/oso/9780190696450.001.0001/oso-9780190696450-chapter-1

Cheng, Charles Davis, 23-42. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020. http://www.jstor.com/stable/j.ctv11cwbg7.5

Fortenbaugh, Robert. “The Nine Capitals of the United States.” United States Senate, 1948. https://www.senate.gov/reference/reference_item/Nine_Capitals_of_the_United_States.htm. Accessed February 13, 2021.

Minosh, Peter. “American Architecture in the Black Atlantic William Thornton’s Design for the United States Capitol” In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited by Irene Cheng, Charles Davis, Mabel O. Wilson, 43-58. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020. http://www.jstor.com/stable/j.ctv11cwbg7.5

Monteiro, Lyra. Power Structures: White Columns, White Marble, White Supremacy, The Intersectionist, 2020. https://intersectionist.medium.com/american-power-structures-white-columns-white-marble-white-supremacy-d43aa091b5f9. Accessed February 15, 2021

Wilson, Mabel O. “Notes on the Virginia Capitol Nation, Race and Slavery in Jefferson’s America.” In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited by Irene

Figures

Figure 1. Northeast perspective view of the U.S Capitol building when first occupied by Congress in 1800. At this point the building consisted of only the north wing, with signs of the construction of the main buildings foundation can be seen in the left of the image. (https://www.capitol.gov/html/IMG_2012030692718.html)

Figure 2. Photograph of the front view of the Virginia State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia. Designed by Jefferson, this building along with Monticello, went on to influence the design of the U.S Capitol in Washington.

Figure 3. An Overseer Doing His Duty near Fredericksburg, Virginia (1798), by Benjamin Henry Latrobe. This scene depicts an aloof white overseer keeping watch over two enslaved women clearing the burnt remains of a forest. This watercolor of the American slave economy can be found among others that Latrobe (English architect that worked on the U.S Capitol in early 1800s) produced during his travels. Slavery was seen as some to be a necessary evil in American society at the time. Courtesy of Maryland Historical Society.

Figure 4. View of the District of Columbia and Georgetown. This eighteenth century painting displays the rural nature of what would become the new federal capital of the United States. George Washington wanted to create a city from scratch, while Henry Latrobe was critical of the move from the developed urban center of Philadelphia. (Philadelphia. Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-530)

Figure 5. William Thornton design of the United States Capitol, Washington, DC, east elevation. Approved design 1794-1797. Here the initially constructed north wing is shown attached to the rest of the completed structure, and the design of a lower, wooden-framed dome is shown that was replaced with a larger cast iron one in the 1850’s.