Henri Labrouste’s Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve is a building of conflicting ideas. On its classical stone exterior the names of 810 authors inscribe a catalog of the most prominent philosophers, scientists and authors of the time. Within its walls, these same author’s works are housed amidst a modern forest of skeletal iron and glass. Just as Labrouste’s attention to historical details root the library in the past his use of modern materials propel it into the future.

Of course, the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve cannot be separated from the real implications of the materials which comprise it. The roll of iron as a material of colonization and the irreparable damage it caused to the colonized peoples who produced it are deeply intertwined with the Bibliotheque and its place in the architectural cannon. In addition, the library as a place of learning, holds the power to control who has access to knowledge as well as the philosophies disseminated within it.

Labrouste’s own philosophies and respect for the Sainte-Genevieve’s historical legacy make these complex dichotomies readily apparent in both the nuanced aesthetics and impressive structure of the building.

A New Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève

After winning the prestigious Grand Prix in 1824, Labrouste spent four years studying in Rome before returning to France with his contemporary, Felix Duban to aid in designing the new Ecole De Beaux-Arts1. A building which was both praised by progressive critics for its new vocabulary of forms and condemned by their conservative counterparts.

Labrouste and Duban’s controversial design won the attention of of the new, post-revolution Liberal government of France who wanted to push Romanticism in the arts2. In 1838, Labrouste was appointed as architecte-en-chef for the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève.

The existing premises for the Bibliothèque had been located in the attic of the College royal de Henri IV3. It had been used so heavily by students of the neighbouring colleges that it became the first library in Paris to introduce gas lanterns to allow studying throughout the night4. However, concerns about the fire safety of this building led to calls for it’s relocation and, eager to design a new building, Labrouste proposed the site for his new Library on Montagne Sainte-Genevieve in 1838.

The building currently on the site, once belonging to College Montaigu and dating back to the 14th century, had since been converted into a prison. Labrouste saw the demolition of this building as a kind of “purification”, returning the site to its original purpose as a place of knowledge5. Indeed Labrouste was very concerned with honouring the history of the original Bibliothèque in his new design. His chosen site not only allowed the library to remain in touch with the historical location but also to retain its original name.

The Historic and the Modern

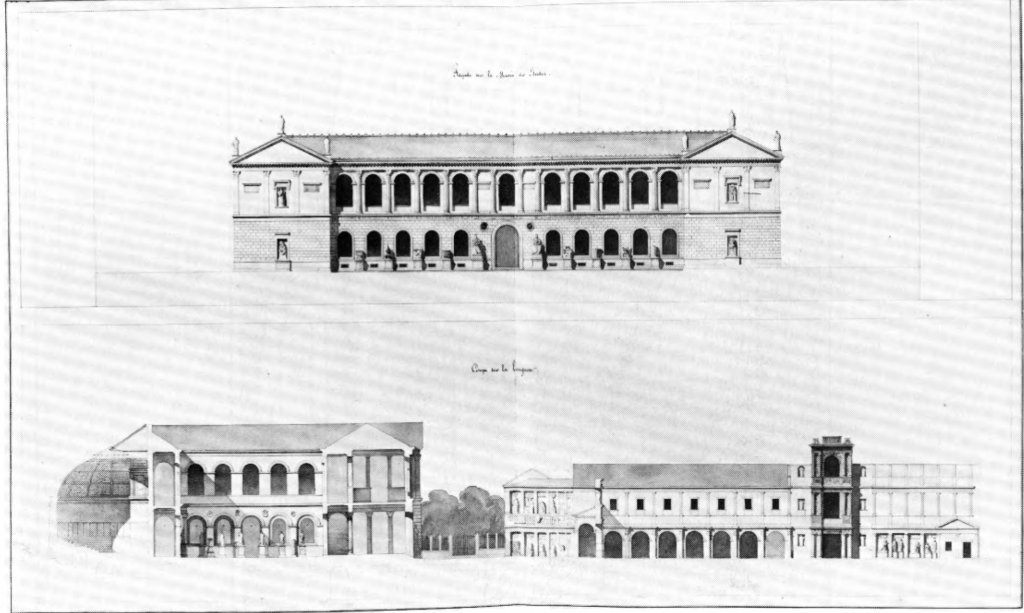

The new Library Sainte-Genevieve began construction in 1845. The building’s exterior making many historical references to its predecessor, while incorporating Labrouste’s own, more modern tastes. The new buildings exterior is of a very classical Romanesque form with a thin entablature encircling it to divide the two floors and garlands suspended below. A row of arched windows runs along the length of the building on the main floor and on the second floor another row of windows are separated by an arcade of regularly spaced pilasters to form the second-floor façade. At the top is a cornice decorated with Greek motifs6

Set into each of the twenty-seven arches on three sides of the building, are panels inscribed with 810 names, beginning with Moses and finishing with the scientist Berzelius7. In this way, the building is taking on the form of a historical register, Labrouste stating:

“This monumental catalog is the principal decoration of the facade as the books themselves are the most beautiful ornament of the interior.” – Henri Labrouste 8 .

At first glance the building evokes a very tomb-like quality with the engraved names giving it the appearance of a mausoleum from the street.

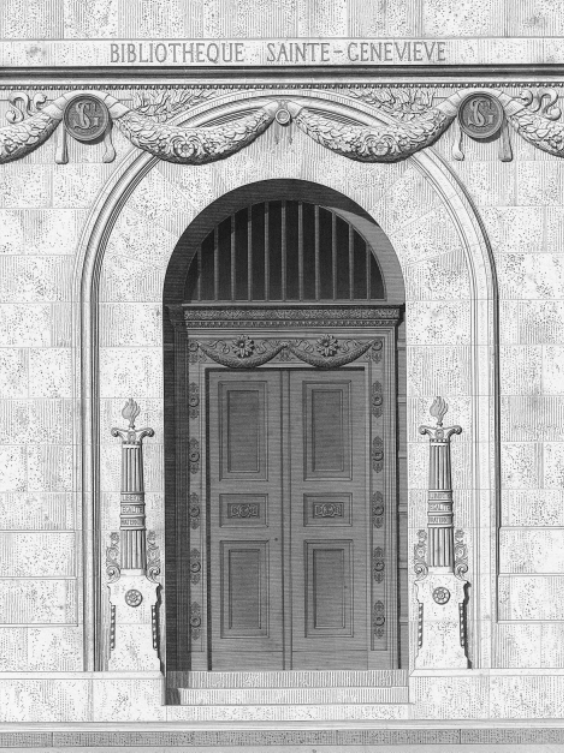

However, this austere exterior form establishes a clear demarcation between the street and the place of learning within. The arched entryway is decorated above by carved swags hung on tie rods and on either side by reliefs of lit lamps, a reference to the original library’s use of oil lamps.

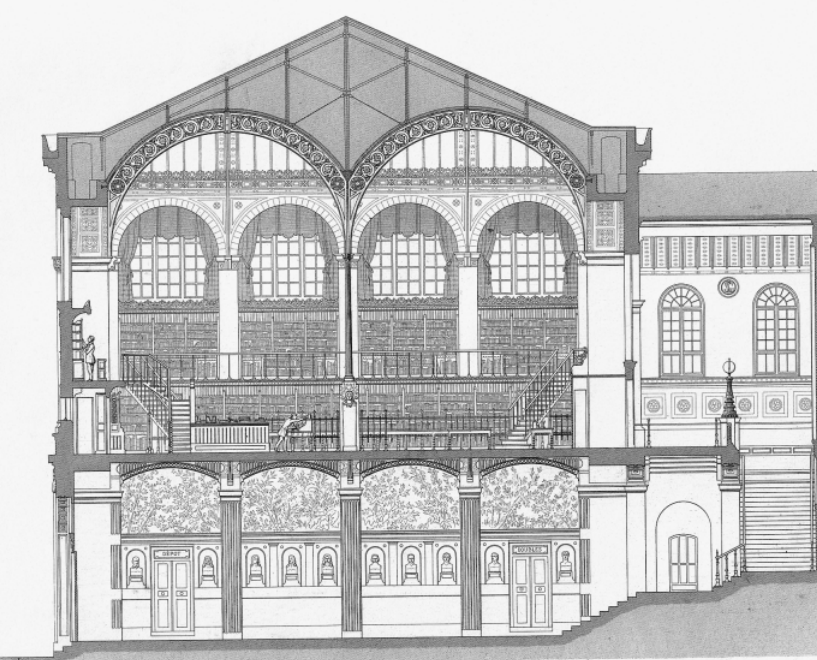

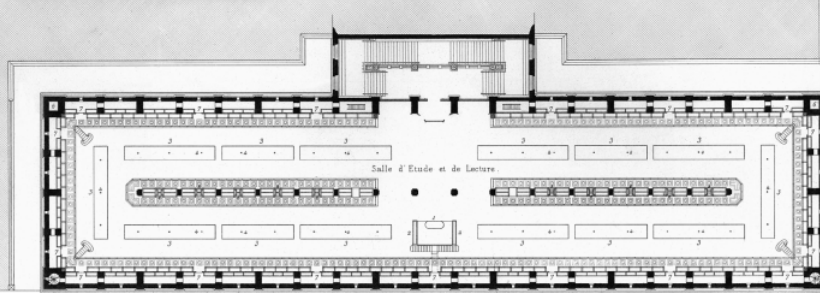

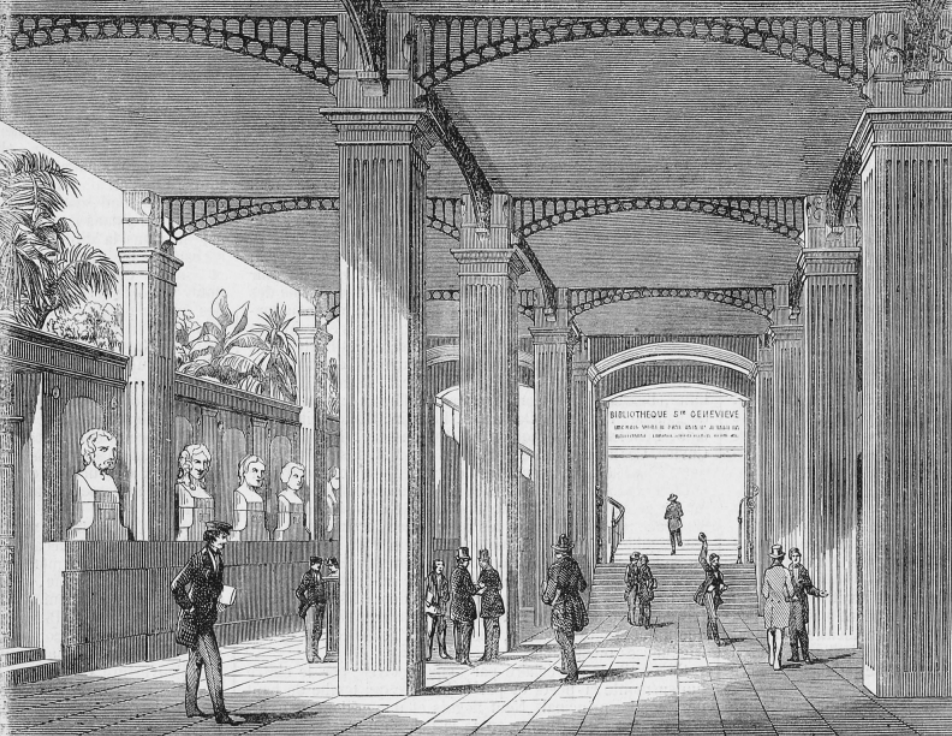

Through this main entrance, a vestibule, book storage and special reading rooms occupy the ground floor, while the main reading room takes up the entire second level. The vestibule space, lovingly dubbed “mon jardin en peinture” (my painted garden) by Labrouste, is intended to evoke the feeling of an ancient garden9. The ceiling is painted in dark blue and the walls are lined with a series of busts of French Philosophers, above which are painted a forest of trees. The space is left intentionally dark to evoke a sense of foliage above one’s head blocking out the sunlight and the rows of large columns conjure the effect of moving through thick trees.

Leaving the vestibule, the visitor ascends a grand staircase leading to a second floor landing that opens into the main reading room.

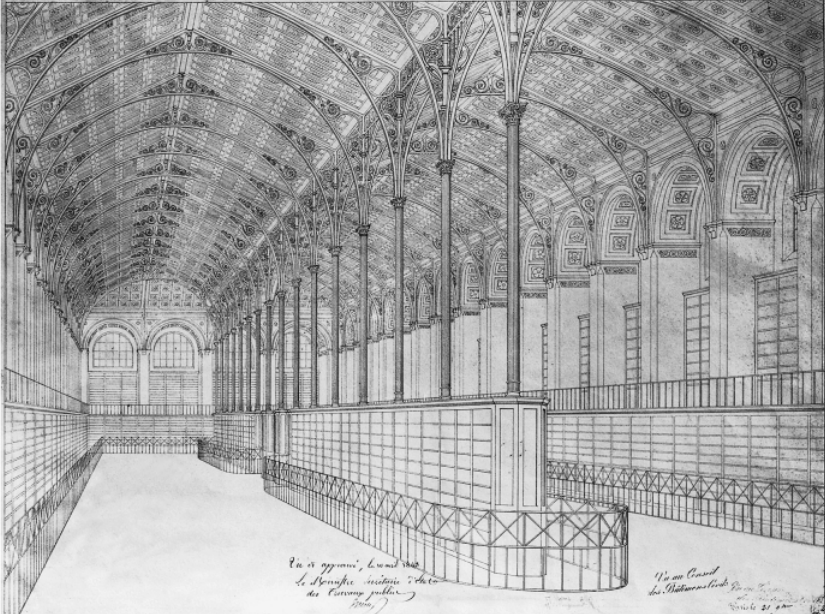

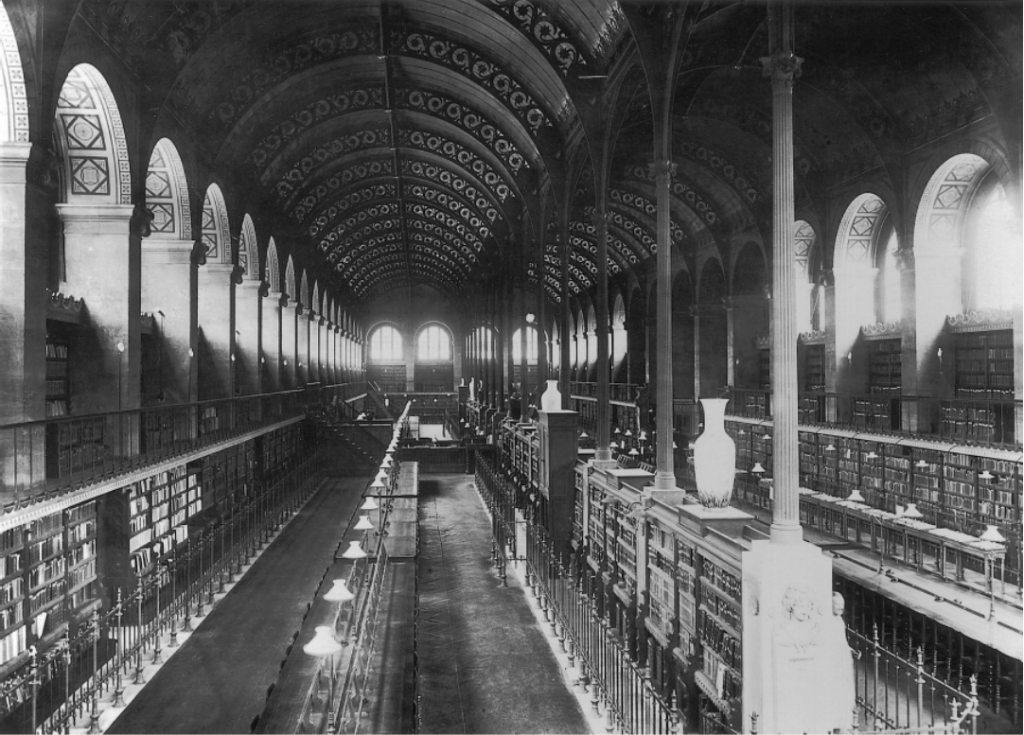

The oblong hall encompassing the main reading room is divided down the middle by a row of tall bookshelves. The room is ringed along the perimeter by more shelves, accessed from a raised walkway of cast iron floor plates which allow light to permeate into the stacks below them10.

The tall arched cage of delicate iron supporting the two barrel vaults above converge into a line of columns running along the central shelves and meld into the exterior walls to frame deep set stone windows.

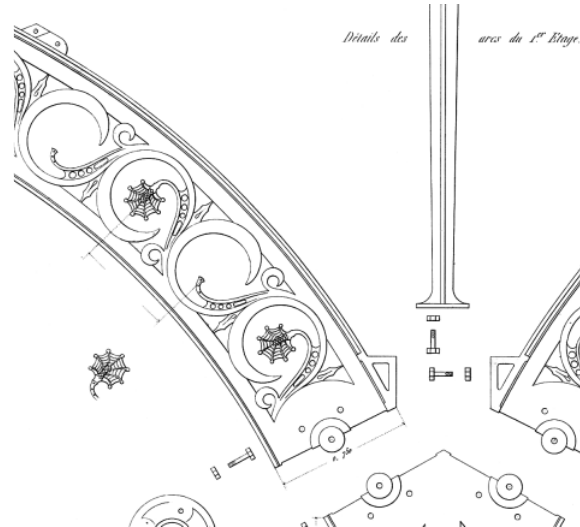

While the use of iron framing was not unheard of in public buildings at the time, the library’s use of such an exposed skeletal iron frame was the first of its kind in architectural history11. The thin, ornate iron and plaster barrel vaults are again intended to symbolize an ancient grove12 and are inset with a circular ornament defined as a fleur by Labrouste, again meant to evoke the vegetal forest characteristics themed throughout the design.

This innovative use of iron material was a point of contention with Labrouste’s clients, the Conseil des Batiments Civils13, who suggested he use more classical stone vaults instead. Labrouste argued that the iron structure could be prefabricated at low cost off-site and considerably shorten the construction period, in the end allowing for his innovation to be retained.

Iron: A framework for Colonization

The material of iron itself is, of course, closely tied to the industrial revolution, which had been underway in Europe for almost a century at the time of the Bibliothèque’s construction. Iron, being representative of a new age of modernity, had been widely used throughout England especially in the construction of factories. This due to its high compressive and tension strength, resistance to fire and capacity for prefabrication. This shift in Europe toward iron as a primary building material held vast implications for the European colonies. These countries were treated as “resource mines” wherein enslaved peoples were used as a primary resource for the production and fabrication of these new materials.

While controversial with Labrouste’s more conservative clientele, the use of iron in framing for public architecture was an established practice at the time throughout Europe. However, this wide and rapid spread of the use of iron is more illustrative of the extractivist ideology of colonialism and presented a sophisticated means of hastening the process of colonization throughout the world. The capacity for prefabrication of iron served as an important tool for colonial expansion, as pieces could arrive and be assembled much more quickly and with far less land than before14.

Throughout the colonies, iron became a tool of control and access as the promise of jobs and industry led to the exploitation and enslavement of more colonized populations.

These far reaching implications extended to countries like the Congo. Ruth Sacks describes the effects of the European iron industry leading Congolese people to forced manual labor, removal of ancestral land rights and causing widespread environmental destruction, just to name a few15. Not isolated to the Congo, a similar story of predatory and extractivist colonialism could be told about many countries throughout the world at this time. The scars of which, have caused irreparable damage still felt today by the ancestors of these colonized peoples.

Perhaps Labrouste found the use of iron to be appropriate in his Bibliothèque for fireproofing concerns, or for its aforementioned potential for prefabrication. Though regardless of intent, the colonial implications of iron cannot be separated from the object of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève or from its place in the historical architectural cannon. Iron was, at the time, the material of colonialism, accelerating the processes of colonization and causing irrevocable damage to the colonized places and people who produced it.

These same themes of colonialism can be extended, in perhaps a more philosophical sense, to the decorative flourishes added throughout the library by Labrouste, such as the the busts of French philosophers placed in the vestibule.

By placing these busts in the entry space, they act as formal gatekeepers of the knowledge within. They represent a hierarchy of thought wherein white, western philosophies are placed in the position of authority over knowledge. The canon of architectural history often views objects like these purely in terms of their cultural and historical significance, thereby empowering the colonial cultures who they represent.

Another example of this privileging can be seen in the 810 names inscribed on the exterior of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. These giving philosophical dominion to the largely Western thinkers portrayed in this list and further prescribing a set of Euro-centric philosophies onto patrons of the library.

Like most of the buildings of its time, the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève cannot be separated from the reality of the materials and social constructions which make up its form. The intricate web of relationships between material and building are numerous, and this entry only begins to skim the surface of the role that one of these materials had in colonization.

Perhaps even more nuanced, is the role such civic buildings played in the control and dissemination of the euro-centric philosophies of the time. Regardless of Labrouste’s own intent, the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève and buildings like it hold a unique power by controlling access to knowledge. These colonial implications mark the Sainte-Geneviève’s place in architectural history as a complex and conflicted one. Evident both in the building’s iconic and impressive structure and in the nuanced ornamental details of its design.

Notes

1. Middleton, Robin. “The Iron Structure of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève as the Basis of a Civic Décor.” AA Files No. 40 (Spring 1999): 48.

2.Van Zanten, David. Designing Paris: the architecture of Duban, Labrouste, Duc, and Vaudoyer. (Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1987), 70.

3. Bressani, Martin & Marc, Grignon. “Henri Labrouste and the Lure of the Real: Romanticism, Rationalism and the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve.” Art History 28, no. 5 (April 2005): 714.

4. Van Zanten, Designing Paris, 88.

5. Bressani, Martin & Marc, Grignon, Henri Labrouste and the Lure of the Real, 715.

6. Francis D. K. Ching, Mark Jarzombek, and Vikramaditya Prakash, A Global History of Architecture, Third edition (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2017), 646.

7. Bressani, Martin & Marc, Grignon, Henri Labrouste and the Lure of the Real, 723.

8. Henri Labrouste, in a letter to Qesar Daly, Revue generale de l’architecture et des travaux publics 10 (1852): cols. 381-82. Cited in Vidler, Books in Space, 127.

9. Bressani, Martin & Marc, Grignon, Henri Labrouste and the Lure of the Real, 728.

10. Vidler, Anthony. “Books in Space: Tradition and Transparency in the Bibliothèque de France.” Representations, No. 42, Special Issue: Future Libraries (Spring, 1993): 122.

11. Van Zanten, David, Designing Paris, 93.

12. Francis D. K. Ching, Mark Jarzombek, and Vikramaditya Prakash, A Global History of Architecture, 646.

13. Van Zanten, David. Designing Paris, 98.

14. Sacks, Ruth. “Lived Remainders: The Contemporary Lives of Iron Hotels in the Congo.” Architectural Theory Review No. 22, (January 2018): 80.

15. Sacks, Ruth, Lived Remainders, 75.

Works Cited

Bressani, Martin & Marc, Grignon. “Henri Labrouste and the Lure of the Real: Romanticism, Rationalism and the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve.” Art History 28, no. 5 (April 2005): 712-751.

Francis D. K. Ching, Mark Jarzombek, and Vikramaditya Prakash, A Global History of Architecture, Third edition (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2017), 646-647.

Henri Labrouste, in a letter to Qesar Daly, Revue generale de l’architecture et des travaux publics 10 (1852): cols. 381-82. Cited in Vidler, Books in Space, 127.

Middleton, Robin. “The Iron Structure of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève as the Basis of a Civic Décor.” AA Files No. 40 (Spring 1999): 33-52.

Sacks, Ruth. “Lived Remainders: The Contemporary Lives of Iron Hotels in the Congo.” Architectural Theory Review No. 22, (January 2018): 64-82.

Van Zanten, David. Designing Paris: the architecture of Duban, Labrouste, Duc, and Vaudoyer. (Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1987), 70-114. Fulcrum E-book.

Vidler, Anthony. “Books in Space: Tradition and Transparency in the Bibliothèque de France.” Representations, No. 42, Special Issue: Future Libraries (Spring, 1993): 115-134.

Figures

Featured Image: Reading room of the Sainte-Genevieve Library–Perspective view, 1842. Pencil and ink, 45×59 cm. Paris: Musee d’Orsay. Photo: Reunion des muses nationaux. Art Resource, New York.

Figure 1: Van Zanten, David. Designing Paris: the architecture of Duban, Labrouste, Duc, and Vaudoyer. (Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1987), 78 Figure 20.

Figure 2: Van Zanten, David. Designing Paris: the architecture of Duban, Labrouste, Duc, and Vaudoyer. (Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1987), 94, Figure 32.

Figure 3: Main door to the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris. Engraving by J. Huguenet, plate 25 from RGATP, 10, 1852. Library of Universite Laval, Quebec.

Figure 4: Sainte-Geneviève Library, Paris-Transverse Section. Engraving by J. Huguenet, plate 26 from RGATP, 10, 1852. Library of Universite Laval, Quebec.

Figure 5: Francis D. K. Ching, Mark Jarzombek, and Vikramaditya Prakash, A Global History of Architecture, Third edition (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2017), 646 Figure 16.90: Plan Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève.

Figure 6: Bressani, Martin & Marc, Grignon. “Henri Labrouste and the Lure of the Real: Romanticism, Rationalism and the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve.” Art History 28, no. 5 (April 2005): 735, Figure 7.11.

Figure 7: Detail of the arches on the second floor. Engraving by J. Huguenet, plate 20 from RGATP, 10, 1852. Library of Universite Laval, Quebec.

Figure 8: Van Zanten, David. Designing Paris: the architecture of Duban, Labrouste, Duc, and Vaudoyer. (Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1987), 97: Figure 34.

Figure 9: Bressani, Martin & Marc, Grignon. “Henri Labrouste and the Lure of the Real: Romanticism, Rationalism and the Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve.” Art History 28, no. 5 (April 2005): 727, Figure 7.6.