The Meiji Restoration

The Meiji period (1868–1912) was decisively an era of construction. It saw the military state of the Tokugawa shogunate replaced with a Westernized nation under a restored imperial authority. One of the most urgent tasks facing the Meiji leaders, who were largely drawn from the early samurai class of the Tokugawa Era (known as daiymo), was constructing a new built environment to conduct the affairs of the state. The old shogunate of Edo lost its political position with the collapse of the Tokugawa era and the rise of Tokyo as the new political capital of the nation. While the heart of Meiji restoration gave birth to what is now Tokyo, the old palaces of the samurai’s leaders were still used to conduct the many affairs of the Imperial government¹. Following the visits to the West by many members of the Imperial government, the architecture of authority slowly began to change. As they documented the uniformity and collectiveness of public and government buildings of France, Britain, and Germany, their wooden gatehouses of the daiymo slowly were replaced with cast iron fences, stone, and brick material². The uncompromising decorative facades and strict symmetrical wings proclaimed their importance with an architectural language of Greek columns and Renaissance inspired pediments and porticos. After presenting their findings to the Emperor, it created an explosive demand for a new architectural typology of public buildings³. The Meiji Emperor recognized the strength of Western-style buildings, particularly of granite stone and brick, and therefore allowed the Meiji government to foresee Japan as a new nation of power and authority.

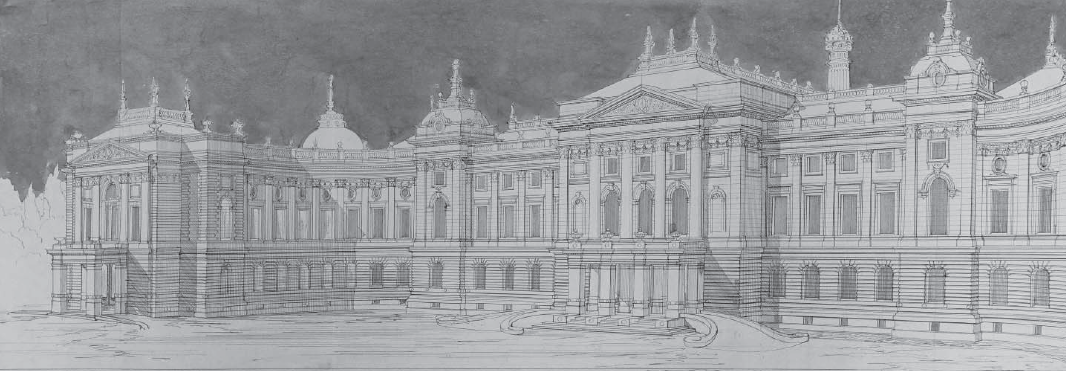

As a result, while Japan entered the Industrial Revolution later than their Western counterparts, it was clear that architecture was charged with a mission of the highest national significance to proclaim Japan’s assurance and authority as a modern state. By culminating Western influence with traditional Japanese architectural motifs as well as rethinking the structural rationale of Japanese palaces, the Akasaka Palace embodies the values of Meiji architecture (figure 1).

¹William H. Coaldrake. “Building the Meiji State.” Architecture and Authority in Japan, Routledge, 2002, pp. 208.

²David B. Stewart, The Making of a Modern Japanese Architecture, 1860 to the Present, Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1987, pp. 60.

³William H. Coaldrake. “Building the Meiji State.” pp. 210.

The Inheritance of a Nation

The palace was built to serve as the official residence of the Crown Prince Yoshihito, who would soon take over the Meiji Emperor after his reign of over 30 years (figure 2). The Meiji Restoration was viewed as the moment when the nation cast off its feudal past and transitioned into an era of civilization and enlightenment. It was critical that the Crown Prince would continue to embody the ideologies set by his predecessor to further the nation into the new era of Japan. As the ascension of the Crown Prince Yoshihito became more imminent, it was imperative to promote the importance of the next emperor. The construction of the Akasaka Palace would then be a tool for the nation to illustrate the importance of the new era of Western civilization evolving beyond Emperor Meiji despite his inevitable death. By adopting similar construction methods as the West, the palace would be a symbol of strength and authority of the imperial institution that the Meiji Restoration had set out to achieve following the fall of the Tokugawa rule.

A New Symbol of Authority

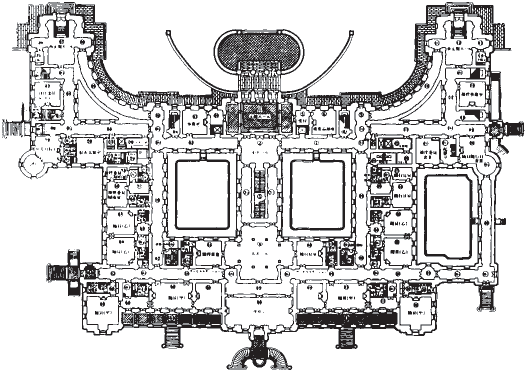

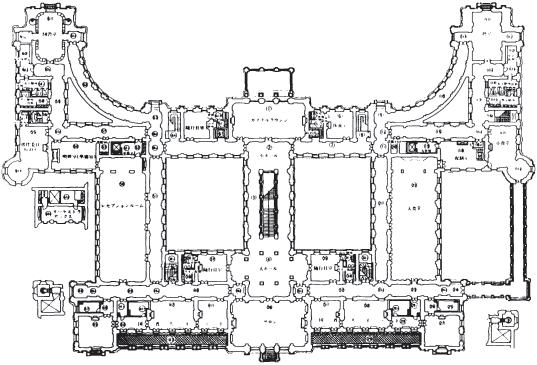

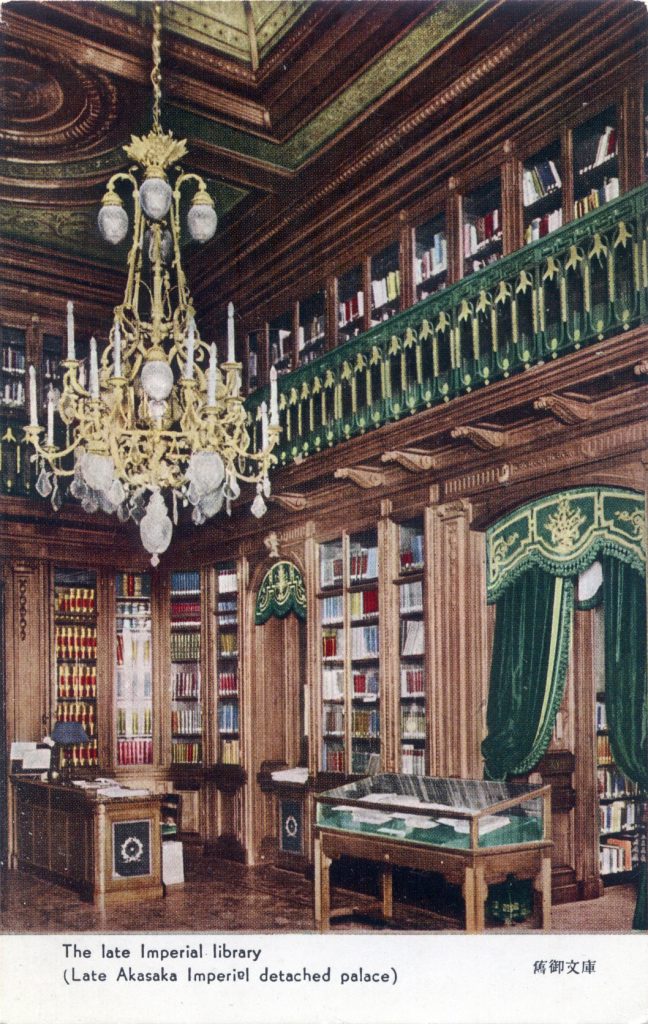

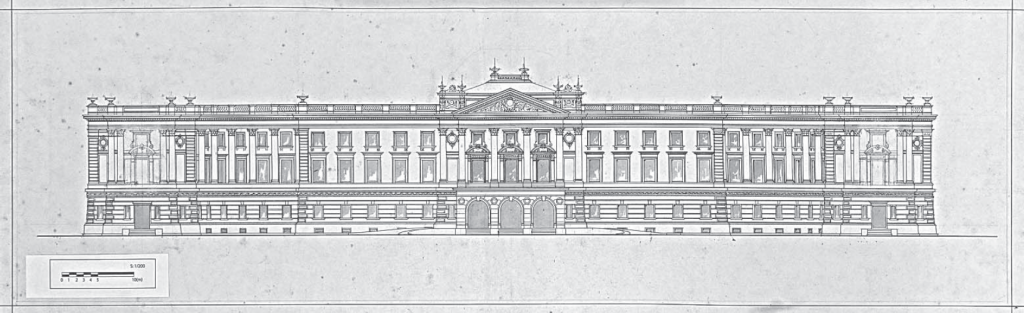

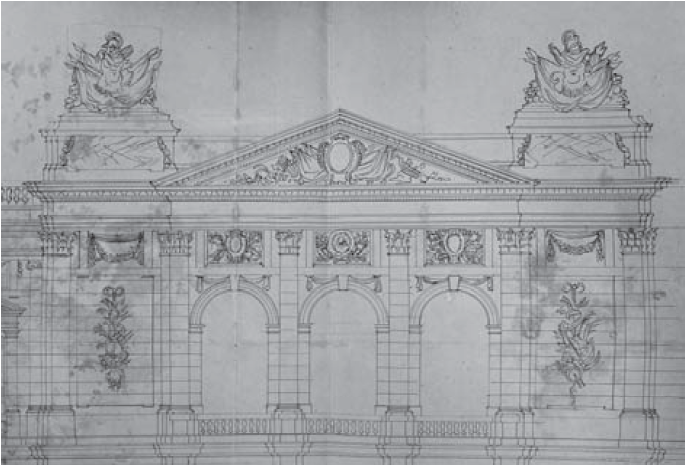

The story of the Palace begins even before entering the building and rather about the land itself. The site was previously used by leaders during the Tokugawa Era, however like many of the land that belonged to the shoguns across the nation, the Imperial government assumed control following the rise of the Meiji Emperor⁴. The building itself is prevalent in its Neo-Baroque style, as pillars and the triangular pediment of the archetypal Greek temple highlights the central entry. The massive granite walls with the repetition of pedimented windows splay out from its central axis in a welcoming arc, demonstrating a graceful balance (figure 3). The symmetry reflected the ideology of the incumbent Emperor and demonstrated a sense of order. This language of order continued within the palace’s private and public rooms. The state rooms, private chambers, and the grand ballroom are exuberance in its Rococo style. Highly ornamented elements were instrumental in defining the nation’s new Emperor as vibrant Corinthian capitals carved on marble columns and arabesque moldings defined the walls and ceilings (figure 4).

In addition to the complete adoption of a new architecture to represent Japan, the palace was a remarkable technological achievement in the use of electrical lighting⁵ (figure 5). Electricity further defined the Palace in the new era of Japan. The lighting illuminated the pillars of the entrance towards the marble staircase and ultimately to the second floor. While the industrial revolution in the United States was a means for economic growth and ultimately the rise of capitalism, Japan saw its innovations as a means to define a new type of power of the soon-to-be Emperor Yoshihito.

⁴Takashi Fujitani. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 76–80.

⁵William H. Coaldrake. “Building the Meiji State.” pp. 215.

The Far Reaches of Knowledge

The high-quality design of the Akasaka Palace was due to the success of the nation employing foreign experts (known as oyatoi) during the Meiji Period. The Imperial government employed over 3000 foreign experts to provide guidance on fields of law, commerce, education, government, science, engineering, and construction⁶. Most importantly, the majority of these oyatoi were associated with the Ministry of Construction who were specialists in the fields of engineering and architecture, illustrating the investment the nation was giving towards building a new Japan. Although designed with specific materials such as stone and brick in a classical architectural style, it must not be forgotten the multitude of expertise that gave birth to the idea that would leave behind a legacy of the Meiji Restoration. The Palace would be a symbol of the conglomeration of knowledge and values that was foreseen by Emperor Meiji. In order to achieve the goal of redefining Japan as a nation, the identity of the palace would include the surplus of knowledge imported from the West but redefined into a new language through traditional practices of Japanese architect Katayama Tokuma.

⁶Ibid, pp. 218.

A New Architectural Language of Japan

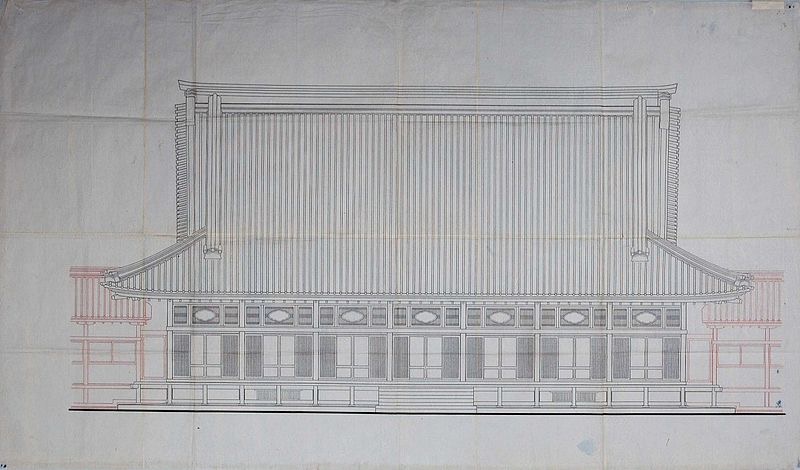

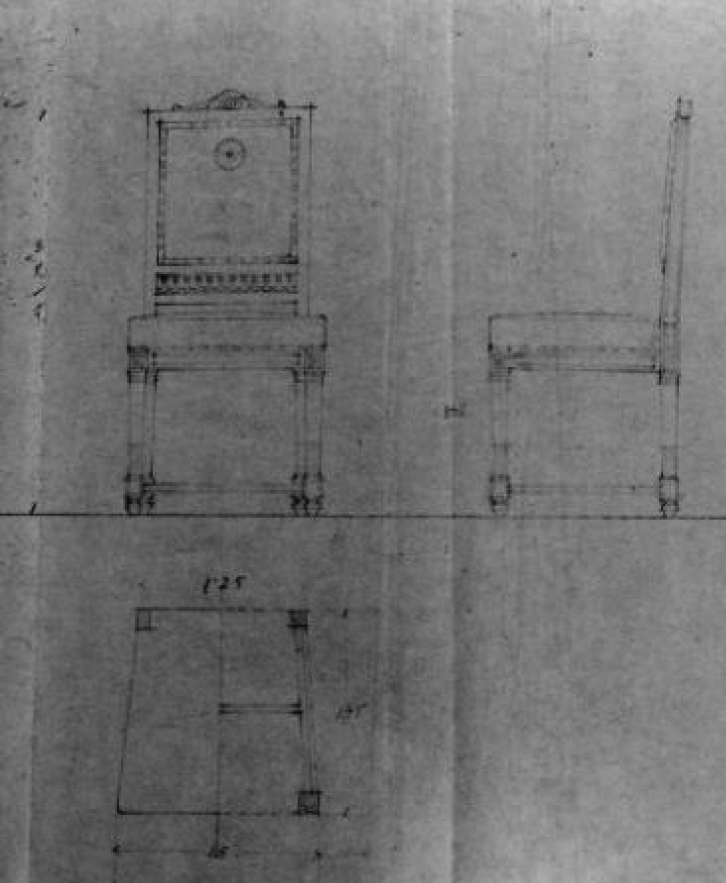

The Palace stood out among many government buildings designed during this time as a result of the technical drawings produced by Tokuma (figure 6). Tokuma was one of the first Japanese architects to be trained in Western architectural practices under the tutelage of Josiah Conder in the 1880s⁷. The Meiji government employed Conder from Britain in 1877 to establish a formal western architectural training program at the Imperial College of Engineering, which Tokuma attended as his star pupil⁸. The goal of the Imperial government was simple: establish the profession of an architect in Japan as defined in contemporary Europe and America. However this became problematic as architects in Europe and America of the 19th century were the product of Renaissance tradition of the artists who designed, rather than traditional Japanese builders who built. This disconnect between the designer and the builder was the challenge Tokuma took on in order to solidify Japan within the Western world. After training with Conder, Tokuma visited various countries in Europe in 1882 to study palace design and he returned to design Emperor Meiji’s Imperial Palace⁹. While his specific duties included the design of the interior spaces that clearly reflected French and German decorative styles, he made sure to preserve the exterior explicitly in traditional Japanese design (figure 7). This allowed Tokuma to illustrate the new Emperor’s Palace as an eclectic Japanese-Western style building that stood as a symbol of a new beginning after the fall of the Tokugawa rule. However, the design of the Imperial Palace was based upon the structural logic of traditional Japanese architecture with timber frame construction. Tokuma quickly understood that this type of engineering could not be applied in the construction of the Akasaka palace, as new materials of stone and brick would not adhere to the same construction methods as timber frame palaces¹⁰. This was a period of technological innovation due to the Industrial Revolution, particularly in steel-framing.

⁷Takashi Fujitani. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 76–80.

⁸Takashi Fujitani. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, pp. 77.

⁹Ibid, 77

¹⁰William H. Coaldrake. “Building the Meiji State.” Architecture and Authority in Japan, Routledge, 2002, pp. 216.

Tokuma’s visit to the United States in the early 1890s exposed him to new construction methods of steel-framing introduced by Edward Shankland¹¹. Shankland was an expert in steel-framing as he developed the structural design of the Manufacturing Building for the Columbia World Exposition in 1893¹² (figure 8). Fascinated with its application, Tokuma ultimately decided on steel as the structural framing for the Palace but had a different structural logic in its application. He devised a way to design the building such that it would be prone to earthquakes that were frequent in Japan¹³. In the United States, steel-framing performed the principal structural framing of the building and the stone attached would be non-structural. In addition, American steel-framed buildings were quite small in comparison to the excessively large palaces of Japan. The existing method used in the United States was neither rigid enough to withstand earthquake shocks nor flexible enough to absorb the seismic energy¹⁴. Tokuma inverts this structural logic in the Akasaka Palace where the stone itself becomes the main structure and the steel-framing assists the weaker parts of the masonry. For the Akasaka Palace, Tokuma discovered it was necessary to create a steel-reinforced masonry structure to withstand natural disasters and in effect created a precedent as to how the palaces would stand tall among the Japanese landscape.

¹¹William H. Coaldrake. “Building the Meiji State.” Architecture and Authority in Japan, Routledge, 2002, pp. 219.

¹² Ibid, pp. 221.

¹³David B. Stewart, The Making of a Modern Japanese Architecture, 1860 to the Present, Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1987, pp. 59–62.

¹⁴Henry Russell Hitchcock, Architecture: the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, (4th edn), Harmondsworth, Mdd: Penguin Books, 1977, p. 169.

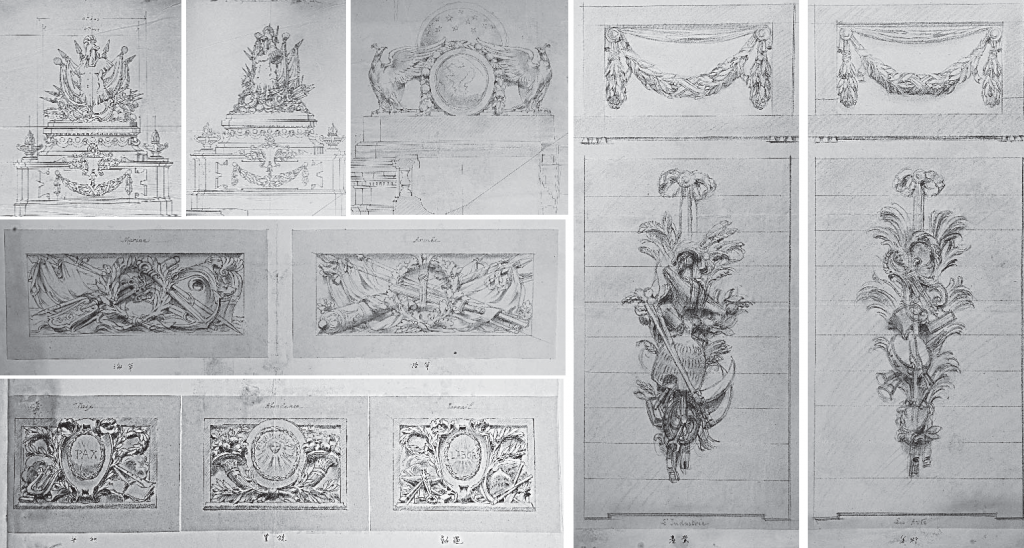

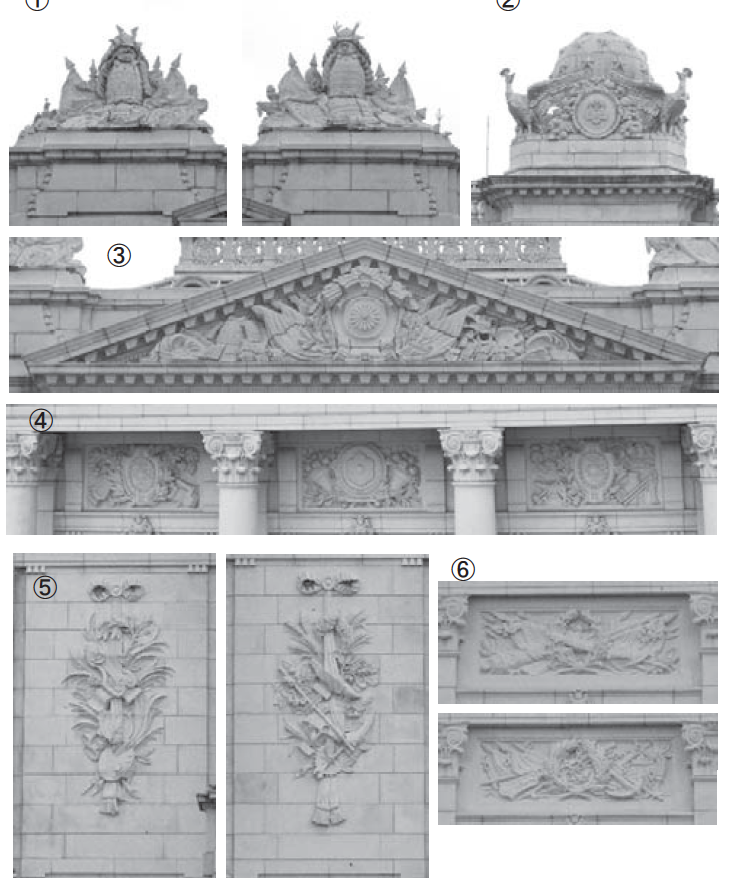

In addition to the technical innovations of the structure, Tokuma coordinated the technical work of various French architectural draftsmen and craftsmen skilled in the detailing the carvings and moldings of the interior¹⁵. The Akasaka Palace displayed a mastery of European interior design but Tokuma takes it one step further by intertwining traditional Japanese motifs. Rather than reproducing the grand style of European Baroque and Rococo style, the intricate detailing of each molding tells a story about the history of Japan over the history of the nation’s Western counterparts. To assist with the identity of the Palace, Tokuma implored Japanese artists of the Meiji Period such as Namikawa Sosuke (1847-1910) and Watanabe Shotei (1851-1918)¹⁶. These artists studied the art of the Renaissance and were able to apply their Japanese skillset with Western influences in their paintings throughout the palace, specifically in the decorative work of Japanese flowers. French interior designers were critical in developing this new architectural language Tokuma set out for the Palace’s design, both in French oil paintings and sculptural moldings. The Hall of Flowers and Birds (known as Kacho no Ma) were decorated with numerous oil paintings of Japanese animals, birds and flowers in a mix of Japanese and European styles (figure 9). In addition, Tokuma went into such detail to ensure that the motifs carved on the interior and exterior of the building exhibited Japanese culture as seen in his initial elevation drawings of the building (figure 10). While African lions of the British Empire decorated the ceilings, their suits were samurai armour. The top of the building are two flanking statues that were also in full samurai armour. The pediment above the central entrance displays the imperial chrysanthemum emblem which is the symbol of the Imperial household¹⁷. To contrast the Japanese style of the moldings, all the furniture were also imported from France (figure 11). Tokuma invents an intriguing dialogue between Japan and the West that allows him to not only create a historic experience but also embody the values set out by the Meiji Restoration into a tangible entity that is the Akasaka Palace.

¹⁵ Amana Hiraga and Sawako Nogushi. Design Process of the Exterior Decoration for the Former Crown Prince’s Palace (Akasaka Palace). Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of Architecture Institute of Japan), vol. 81, no. 726, 2016, pp. 1773–1782., doi:10.3130/aija.81.1773.

¹⁶ William H. Coaldrake. “Building the Meiji State.” pp. 221.

¹⁷ Kazuko Koizumi, Yumiko Maegata, Chiaki Sugasaki, Amana Hiraga. A Study of the Interior Decoration and Furniture in the Former Crown Prince’s Palace (Akasaka Palace). Journal of the Housing Research Foundation “Jusoken”, vol. 40, 2014, pp. 95-106, https://doi.org/10.20803/jusokenronbun.40.0_95

The “Starchitect” of Japan

The innovation in the structural integrity of the building in addition to the decorative Japanese motifs infused with Renaissance design allowed Tokuma to bridge the connection between the designer and the builder. Tokuma gathered expertise of American and European knowledge and adjusted it to fit beautifully within the unique setting of Japan prone to earthquakes. A key aspect of the Palace’s design is seen in the orthographic drawings produced by Tokuma. Before travelling to the United States, the drawings were completed that emphasized the strong desire to improve the identity of the building by combining Japanese and European art¹⁸. This design intent to include Japanese motifs before construction began demonstrated the success of Tokuma as a revolutionary architect of Japan with his commitment from the beginning of the project. While the story of the Akasaka Palace is a realization of the legacy set out by the Meiji Emperor to be passed down for generations, it also reveals the story of redefining the architectural profession. As a result, Meiji architecture is seen as a product of Tokuma’s Akasaka Palace where the job of the architect is neither an artistic profession nor a structural rationale. More importantly, the architect is a conglomeration of knowledge derived from a multitude of cultures to discover ways to influence one another that integrates engineering with the beautiful.

¹⁸Kazuko et al. A Study of the Interior Decoration and Furniture in the Former Crown Prince’s Palace (Akasaka Palace). Journal of the Housing Research Foundation “Jusoken”, vol. 40, 2014, pp. 95-106, https://doi.org/10.20803/jusokenronbun.40.0_95

References

- William H. Coaldrake. “Building the Meiji State.” Architecture and Authority in Japan, Routledge, 2002, pp. 208–222.

- David John Lu (ed.) Sources of Japanese History, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1974, vol. 2, p. 36.

- David B. Stewart, The Making of a Modern Japanese Architecture, 1860 to the Present, Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1987, pp. 59–62. (materials and construction resource for the building of the akasaka palace)

- Henry Russell Hitchcock, Architecture: the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, (4th edn), Harmondsworth, Mdd: Penguin Books, 1977, p. 169.

- Interview with Katayama Tokuma, Nihon shinbun, 17 May, 1907. Shinbun shusei Meiji hennenshi (op. cit. note 14), vol. 13, p. 257.

- Amana Hiraga and Sawako Nogushi. Design Process of the Exterior Decoration for the Former Crown Prince’s Palace (Akasaka Palace). Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of Architecture Institute of Japan), vol. 81, no. 726, 2016, pp. 1773–1782., doi:10.3130/aija.81.1773.

- Kazuko Koizumi, Yumiko Maegata, Chiaki Sugasaki, Amana Hiraga. A Study of the Interior Decoration and Furniture in the Former Crown Prince’s Palace (Akasaka Palace). Journal of the Housing Research Foundation “Jusoken”, vol. 40, 2014, pp. 95-106, https://doi.org/10.20803/jusokenronbun.40.0_95

- Takashi Fujitani. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, University of California Press, 1998, pp. 76–80.

Images

figure 1: Main Facade Image of the Akasaka Palace, Geihinkan and Masuda Akihisa (Akasaka Palace now know as the State Guest House)

figure 2: Mainichi Newspaper, “Portrait of the Fourth Emperor”, Imperial Household Agency, 1912.

figure 3: Floor Plans of the Akasaka Palace, Geihinkan and Masuda Akihisa (Akasaka Palace now know as the State Guest House)

figure 4: Interior Images of the Palace, http://www.oldtokyo.com/akasaka-detached-palace/

figure 5: Main entry of the Palace, Geihinkan and Masuda Akihisa (Akasaka Palace now know as the State Guest House)

figure 6: Elevation drawing by Katayama Tokuma. Amana Hiraga and Sawako Nogushi. Design Process of the Exterior Decoration for the Former Crown Prince’s Palace (Akasaka Palace). Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of Architecture Institute of Japan), vol. 81, no. 726, 2016, pp. 1776., doi:10.3130/aija.81.1773.early 1890s.

figure 7: Interior image of the Tokyo Imperial Castle. Public Domain. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Tokyo_Imperial_Palaceof the Tokyo Imperial Castle.

Exterior Drawing Audience Hall elevation drawing. Tokyo Metropolitan Library. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tokyo_Imperial_Palace_pic_09.jpg

figure 8: Interior image of the Manufacturing Building. https://chicagology.com/columbiaexpo/fair010/

figure 9: Interior images. https://www.geihinkan.go.jp/en/akasaka/

figure 10: Elevation, Detailed Drawings, and Finished Scuptures. Kazuko Koizumi, Yumiko Maegata, Chiaki Sugasaki, Amana Hiraga. A Study of the Interior Decoration and Furniture in the Former Crown Prince’s Palace (Akasaka Palace). Journal of the Housing Research Foundation “Jusoken”, vol. 40, 2014, pp. 95-106.

figure 11: Detailed drawing of furniture. Kazuko Koizumi, Yumiko Maegata, Chiaki Sugasaki, Amana Hiraga. A Study of the Interior Decoration and Furniture in the Former Crown Prince’s Palace (Akasaka Palace). Journal of the Housing Research Foundation “Jusoken”, vol. 40, 2014, pp. 104.