All the colors, creeds, breeds, and voices become Rangoon; Rangoon was born in Rangoon, Rangoon was raised in Rangoon, Rangoon stood on par with other cities around the world. Proud Rangoon, the son of an urban city: (From Dressmaker Rangoon by Maung Chaw Nwe and translated by Kenneth Wong, 2013)1

The growth of British control over the Kingdom of Burma was incremental over decades, expanding inward in a trilogy of wars. Gaining Lower Burma and Rangoon in the Second Anglo-Burmese War, the British settler government quickly turned focus to consolidating their hold over the Burmese port capital, deconstructing and redeveloping the urban fabric to suit the needs and ideologies of the colonizing power. Introducing Montgomerie and Lieutenant Fraser’s plan for the city in 1852, they would wholesale-borrow Rafflesian principles employed in the 1819 British colonization of Singapore, centering their scheme for the redevelopment of Rangoon on the island-situated Sule Pagoda and imposing a rectangular grid over the city.2 Dependent on systems of land seizure, resale, and concepts of tabula rasa, the Montgomerie-Fraser plan for Rangoon marginalised and expelled Burma’s indigenous population and Buddhist faith, inadvertently dislocating each from the control and secularity of the planned urban fabric and creating platforms for nationalist Burmese-Buddhist decolonialism.

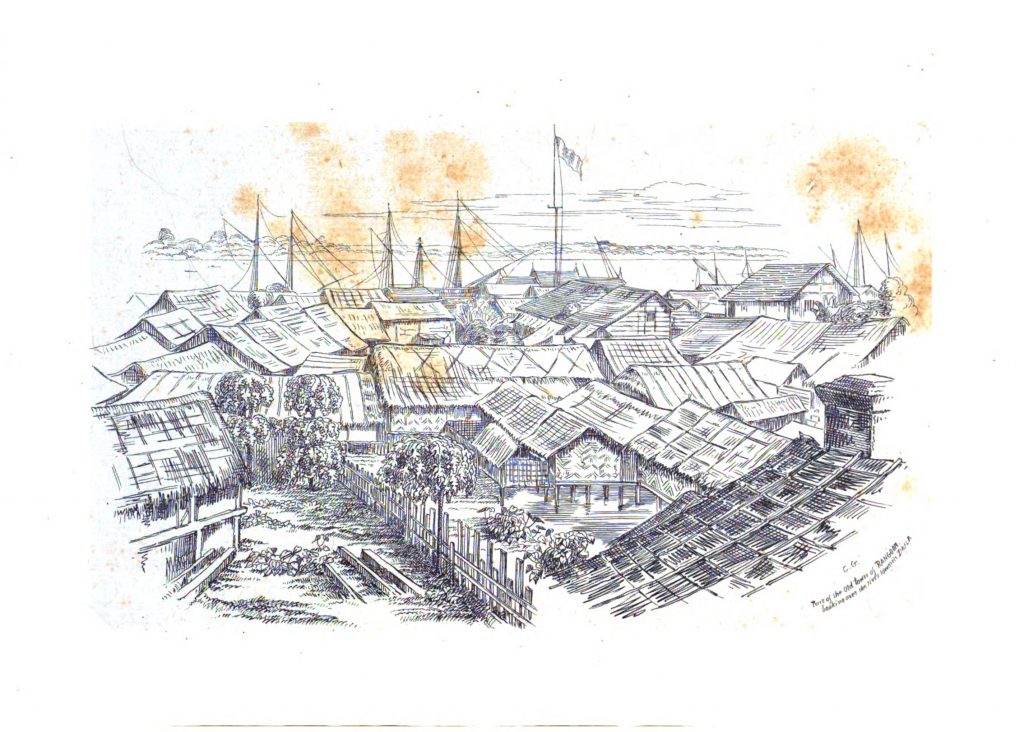

Colesworthy Grant, Rough Pencillings of a Rough Trip to Rangoon in 1846 (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, 1853).

A pencil sketch of Rangoon’s port town fabric prior British annexation following the Second Anglo-Burmese war.

The annexation, as well as the following destruction and reconstruction of Rangoon was motivated and organised by economic avarice of British settlers and merchants, permitted by a disregard for Burma’s sovereignty and people. In a series of events outlined by Pollak, the Second Anglo-Burmese war that resulted in the British consolidation of Rangoon was spawned from a tangle of conflicting interests and ideals within the settling European organizations. Sparking from mercantile conflict over teak, Christian missionaries and British traders would exert their influence to deceive a naval officer, ultimately precipitating war largely undesired by the settler government in Calcutta.3 The contempt held by British colonists illuminated by Pollak’s account,4 is evidenced again in the tabula rasa strategy adopted by Montgomerie and Fraser following the war. As described by Turner, preoccupation Rangoon was composed of two distinct towns – a much older port settlement that hosted the majority of non-Burmese traders, and a better fortified community nearer the Shwedagon Pagoda built during the First Anglo-Burmese War.5 While the landscape of Lower Burma was being transformed by the extractive economy of British Imperialism, the increasing demand for exported rice in particular resulting in mass clearing of the Irrawaddy delta,6 Rangoon was drained and deconstructed to better conform to European ideals of urban form and suit their unilateral conception of a colonized port city, imposing a grid system, militarily occupying the Shwedagon Pagoda, and converting the surrounding land and nearby town into garden and military cantonments respectively.7 We can also observe this false identification of tabula rasa in later recounts of the settler government’s construction efforts, Webb oozing praise for the colonial administration, describes their efforts as “an “excellent start given to the development of Rangoon”8 illuminating the disdain held for Burmese culture and peoples, additionally affirming Rangoon as undeveloped and the people as other, permitting British settlers to approach the city and landscape as if it was uninhabited. The same disregard was what enabled the seizure of land and property necessary for the Montgomerie-Fraser Plan.

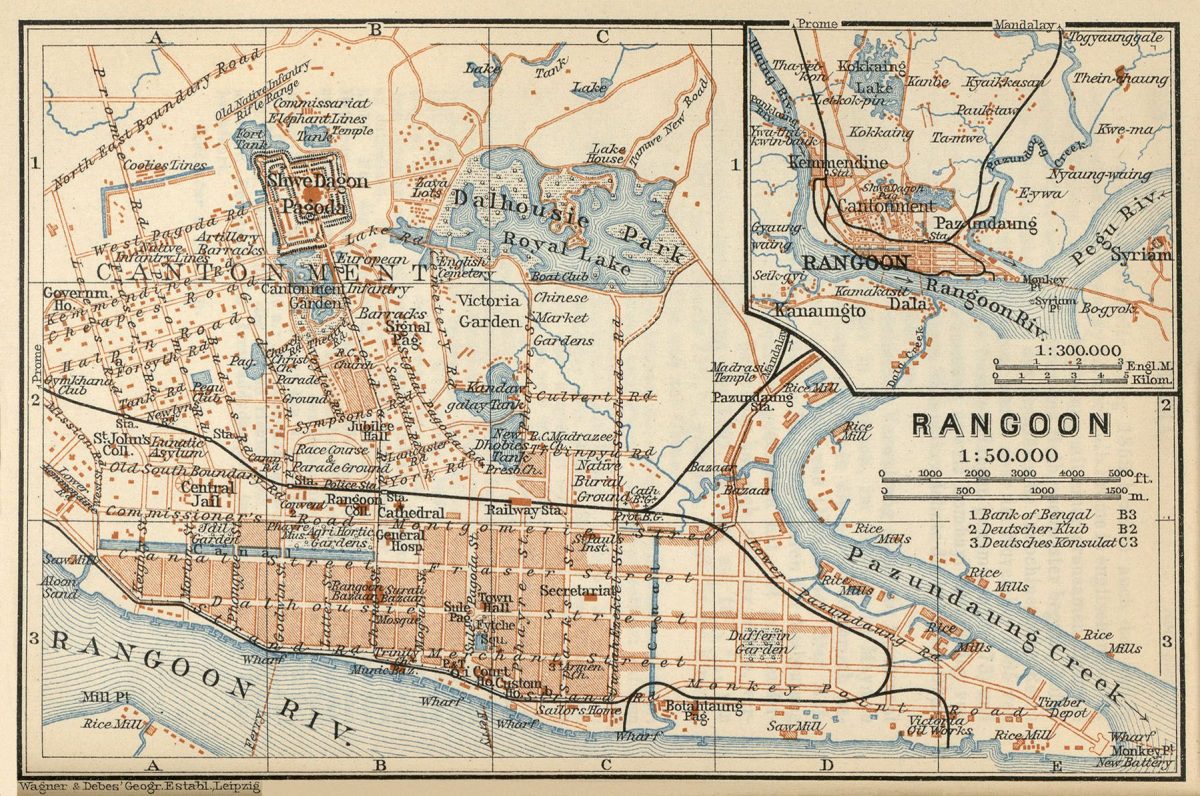

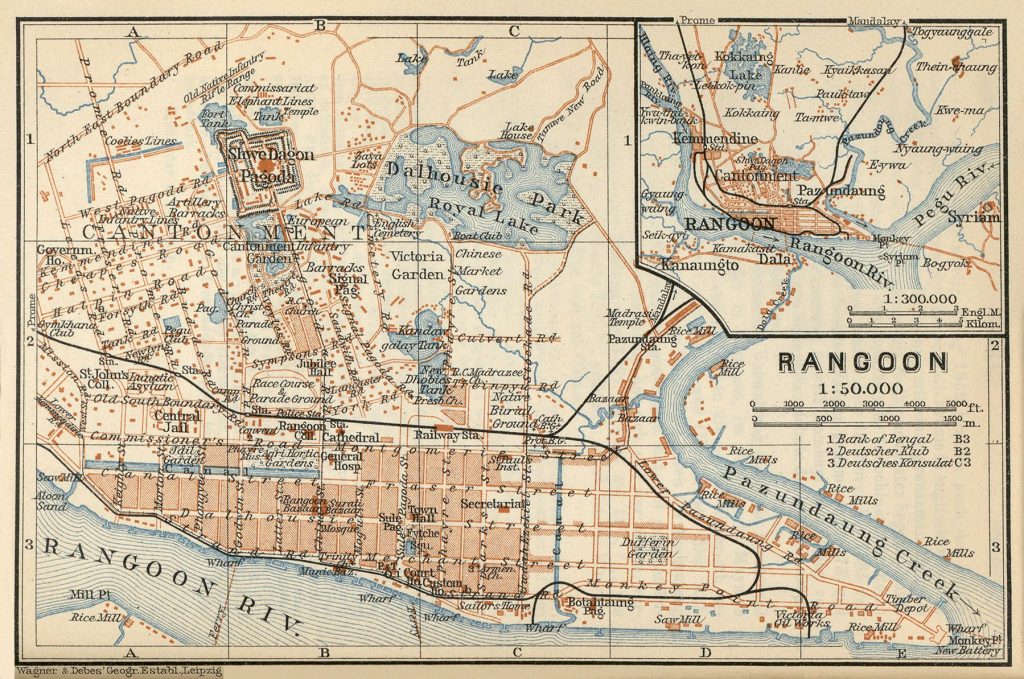

Karl Baedeker, Indien. Handbuch fur Reisande (Leipzig: Verlag von Karl Baedeker, 1914).

A later made, detailed, mapping of Rangoon displaying the Montgomerie-Fraser Grid System, the appropriation of the area surrounding the Shwedagon Pagoda as cantonment, as well as the artificial Royal Lake.

The massive deconstruction and redevelopment of the Montgomerie-Fraser plan was accomplished by the seizure, appropriation, classification, and sale of Rangoon’s urban fabric enabled by the imposed grid system. The grid system commonly applied in British colonial projects, though vaunted by the planners as an objective and neutral system9 to control the density and growth of urban fabric, also quite crucially influences the size and shape of buildings altering the built architecture of communities. Far displaced from neutral, the idea of European hierarchy is embedded into the institution of city grids, Kostof explaining “… the grid inscribed the social preeminence of a property-owning class, a kind of territorial aristocracy. The first settlers divided the land and thereby ensured themselves the power to govern the affairs of the city.”10 Focusing on the proceedings in Rangoon following the British conquest, the settler government quickly declared the urban area government property and the grid of 30.5 metre streets, parceled into 244 by 259 metre blocks.11 Drawing on a series of letters between Commissioner Arthur Phayre the British Lord Dalhousie Governor-General of India to recount events, Phayre instructing to give “no recognition [] to previous land titles. Those residing on plots of land in the new city would have the first right to purchase it, but no other claim.”12 Furthermore, strict laws mandating construction on the lands mandating brick, cement and pucca, instead of the customary wood structures that characterized pre colonial Rangoon priced out the original inhabitants, while property on the most prominent streets and riverside was reserved for businesses deemed important in the “colonial determination”.13 Additionally, space was hierarchically racialized, ethnic districts laid out excluding the Burmese, forcing the population into newly forming communities in undrained land outside of pre colonial Rangoon. The sale of the seized land would be a prominent source of income to the government for the next 20 years, used to fund infrastructure projects. In 1872, following the sale of all available land within the grid, the government turned to the suburbs now cleared by the expelled Burmese populace, introducing 5 to 15 year leases for the already inhabited land. Describing this system of exploitation, Rhoads points out that a similar pattern of land seizure, expulsion, and neglect, would be repeated by governments in Rangoon, and later Yangon, as a tool of control.14 Outside of the order of Rangoon’s grid, this urban periphery would grow to host Rangoon’s Burmese population and become a platform for Burmese decolonialism.

Howard-Moore and Osiri, “Urban Forms and Civic Space in Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth-Century Bangkok and Rangoon,” Journal of Urban History 40, no.1 (2014): 172.

A photograph displaying the Sule Pagoda situated in the centre of the Montgomerie-Fraser planning scheme. In juxtaposition is Ripon hall, the location of which would later be a town hall. This photograph both displays the tension and dichotomy in Rangoons urban fabric, and has persisted in Yangon.

Despite the European colonizing government efforts in employing the urban fabric as a system of control, Rangoon’s Buddhist superstructure persisted through the occupation, providing a unifying platform and infrastructure for decolonial resistance. Relying again on Turner’s observations, by consequence of the purposeful exclusion of the Burmese populace from the core of the city, the Burmese were also removed from the strictest control imposed by the urban fabric, and the resultant secular and ethnic division propagated within. In contrast to the Sule and Shwedagon Pagodas that, while figuring prominently in Rangoon’s religious and urban landscapes, were subject to British diminishment and control, Turner points particularly to Thayettaw monastery complex on the edge of the organized grid, illustrating a place anathema to the colonial order ordained elsewhere, that actively resisted colonial regulation.15 Buddhist resistance to governmental regime, both colonial and later, would remain a prominent concern, Ware arguing that the marginalisation of the Burmese population, and by association Buddhism, was the root of Burma’s, and later Myanmar’s, fervent Burmese and Buddhist nationalism.16 Ware also argues that the settler government’s attempts to stifle Buddhism within Rangoon, was partially due to the influence and connection between the monarchy of northern Burma and Shwedagon Pagoda, that had a primacy within Burmese Buddhism and still enjoyed the patronage of Northern Burma’s monarchy.17 Despite the Shwedagon Pagoda’s military occupation, the site remained a sharp point of conflict between the settler government and Rangoon’s Buddhist population,18 explaining their wariness of the relation as it related to their continued control.

Employing strategies of tabula rasa and land seizure, the Montgomerie-Fraser Plan inscribed a grid into the landscape of Rangoon, as a tool for control and secularity within the lives of the city’s ethnic populations. By attempting to suppress Rangoon’s indigenous populace and create their image of an ideal, eurocentric city by expelling indigenous Burmese from the ordered fabric of Rangoon’s core, they were inadvertently released from the secularity enforced by the inscribed grid, enabling the continued persistence of Burma’s indigenous identity, and the growth of a Burmese-Buddhist nationalism and decolonial resistance that remains present today.

Footnotes:

- Kenneth Wong, “‘Dressmaker Rangoon’ by Maung Chaw Nwe”, Kenneth Wong SF: Wanderlust, Writing Life, and Curious Contemplations, Kennth Wong, Published October 15, 2013, http://kennethwongsf.blogspot.com/2013/10/dressmaker-rangoon-by-maung-chaw-nwe.html.

- Robert Home, “Port Cities of the British Empire: ‘A Global Thalassocracy’,” in Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities (New York and London: Routledge, 2013), 72.

- Oliver Pollak, “The Origins of the Second Anglo Burmese War (1852-53)”, Modern Asian Studies 12, no. 3 (1978): 483-502.

- Ibid.

- Alicia Turner, “Colonial secularism built in brick: Religion in Rangoon,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 52, no.1 (2021): 29-30.

- Yda Saueressig-Schreuder, “The Impact of British Colonial Rule on the Urban Hierarchy of Burma”, Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 10, no. 2 (1986): 245-247.

- Turner, 34-38.

- C. Webb, “The Development of Rangoon”, The Town Planning Review 10, no. 1 (1923): 38.

- Tuner, 28.

- Spiro Kostof, A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 140-141.

- Home, 72.

- Turner, 35-36.

- Ibid.

- Elizabeth Rhoads, “Forced Evictions as Urban Planning? Traces of Colonial Land Control Practices in Yangon, Myanmar,” State Crime Journal, Autumn (2018): 278-286.

- Turner, 41-47.

- Anthony Ware, “Origins of Buddhist nationalism in Myanmar/Burma: An urban history of religious space, social integration and marginalisation in colonial Rangoon after 1852,” in Religion and Urbanism (London: Routledge, 2015), 27-45.

- Ware, 40-41.

- Elizabeth Howard-Moore and Nathanath Osiri, “Urban Forms and Civic Space in Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth-Century Bangkok and Rangoon,” Journal of Urban History 40, no.1 (2014): 174.

Bibliography:

Baedeker, Karl. Indien. Handbuch fur Reisande. Leipzig: Verlag von Karl Baedeker, 1914.

Grant, Colesworthy. Rough Pencillings of a Rough Trip to Rangoon in 1846. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, 1853.

Home, Robert. “Port Cities of the British Empire: ‘A Global Thalassocracy’.” In Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities, 64-91. New York and London: Routledge, 2013.

Howard-Moore, Elizabeth, and Nathanath Osiri. “Urban Forms and Civic Space in Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth-Century Bangkok and Rangoon.” Journal of Urban History 40, no.1 (2014): 158-177..

Kostof, Spiro. A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Pollak, Oliver. “The Origins of the Second Anglo Burmese War (1852-53).” Modern Asian Studies 12, no. 3 (1978): 483-502.

Rhoads, Elizabeth. “Forced Evictions as Urban Planning? Traces of Colonial Land Control Practices in

Yangon, Myanmar.” State Crime Journal, Autumn (2018): 278-305..

Saueressig-Schreuder, Yda. “The Impact of British Colonial Rule on the Urban Hierarchy of Burma.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 10, no. 2 (1986): 245-277.

Turner, Alicia. “Colonial secularism built in brick: Religion in Rangoon.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 52, no.1 (2021): 26-48.

Webb, C.. “The Development of Rangoon.” The Town Planning Review 10, no. 1 (1923): 37-42.

Ware, Anthony. “Origins of Buddhist nationalism in Myanmar/Burma: An urban history of religious space, social integration and marginalisation in colonial Rangoon after 1852.” In Religion and Urbanism, 27-45. New York and London: Routledge, 2015.

Wong, Kenneth. “‘Dressmaker Rangoon’ by Maung Chaw Nwe.” Kenneth Wong SF: Wanderlust, Writing Life, and Curious Contemplations. Kennth Wong, Published October 15, 2013. http://kennethwongsf.blogspot.com/2013/10/dressmaker-rangoon-by-maung-chaw-nwe.html.