The Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Saigon, constructed between 1877 and 18801, can be considered a garish example of French colonial architecture located in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. The religious structure, officially, the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of The Immaculate Conception was commissioned by Bishop Lefevre and designed by Jules Bourard.2 One will note the blatant similarity between the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, France and the one in Vietnam. The historical importance of this building can be attributed to the French occupation of Indochina, in which the combination of religion and architecture was used as a means of spreading French beliefs, maintaining control, and displaying power. This analysis will thus examine the events that led towards the development of Vietnam and the introduction of Catholicism, as a framework to better understand the Cathedral’s architecture and its legacy over time.

1. Vo, Nghia M.. Saigon: A History. Ukraine: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers, 2011.

2. Njoh, Ambe J. “French Urbanism in Indochina.” In, 89-113. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015.

French-Indochina

The French colonization of Indochina began in 1858 and ended in 1956.2 The desire to control this region was mainly for territorial expansion, economic incentives, and religious agendas.2 One of the ways in which the French attempted to control the region was through infrastructure, urban planning, and architecture. In particular, Njoh argues that the development of transportation infrastructure was crucial to colonial interests.2 Better road networks allowed efficient transport of goods and materials for exports, and soldiers could easily be deployed to repel other European interests or anti-colonialists.2 Within the same regard, Kim argues that for France, colonial infrastructural projects were seen as experiments to achieve the ideal city that could promote French interests.3 The development of streets and sidewalks were thus deemed important and were also used to manage racial zoning. In Saigon, sidewalks were heavily managed with strict rules and regulations for health and aesthetic reasons.3 A plan view of Saigon (Figure 2) shows how infrastructure was developed in the region with gridded street networks commonly found in European practices. The importance of water is also highlighted and gives a further incentive for urban expansion. The plan also shows French labeling and colour-coded areas that reflect zones of importance and non-importance typically found in colonial maps. In addition to infrastructural projects, religion was also used to further colonial conquests.

The Roman Catholic Church also collaborated with the French government during this time.2 In this way, one can conclude that religion was used to justify colonial acts. For example, missionaries played vital roles serving as interpreters that assisted in colonial expansion within the region.2 When Catholicism was introduced in Vietnam, numerous Buddhist practitioners converted to the new religion.4 Naturally, conflicts emerged between Catholicism and Buddhism under French rule. Catholic missionaries were given favorable social, economic, and political status, and priests abused their power that allowed them to destroy Buddhist temples and replace Buddhist symbols with Catholic ones.4 In particular, and among other Catholic churches, the Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Saigon was constructed on top of a Buddhist temple.4 In one perspective, it would appear religion was used as a colonial device and a social status symbol. In another perspective, the Roman Catholic Church used colonialism as an avenue through which Catholicism could thrive.

2. Njoh, Ambe J. “French Urbanism in Indochina.” In, 89-113. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015.

3. Kim, Annette M. “A History of Messiness: Order and Resilience on the Sidewalks of Ho Chi Minh City.” In Messy Urbanism: Understanding the “Other” Cities of Asia, edited by Chalana Manish and Hou Jeffrey, 22-39. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2016. Accessed April 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1d4tz9d.7.

4. Nguyen, Hung Thanh. “Buddhist-Catholic Relations in Ho Chi Minh City.” International Journal of Dharma Studies 5, no. 1 (2017): 1.

The Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Saigon

The immediate connection one can draw between the Cathedral in Ho Chi Minh City and French colonialism is its resemblance to the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, France. However, the main visual difference is the use of red-colored brick that was imported from France and was used in its construction.5 This material would have been easier to transport longer distances than stone and signifies the lengths it took to bring a locally sourced material into a foreign land, literally solidifying France’s presence. Another notable feature of the Cathedral are the two bell towers that were installed later in 1895.1 The architectural feat of this building represents the ingenuity of French designers adapting local techniques within a foreign setting.

The Romanesque architectural style of the Cathedral represents Eurocentric values commonly found in religious structures throughout Europe. Furthermore, the stained-glass windows also reflect the Cathedral aesthetic and artful depictions of a foreign religion (Figure 3). A further look at the interior of the nave (Figure 4) reveals the shear height of the building, distinguishing the space for religious contemplation.

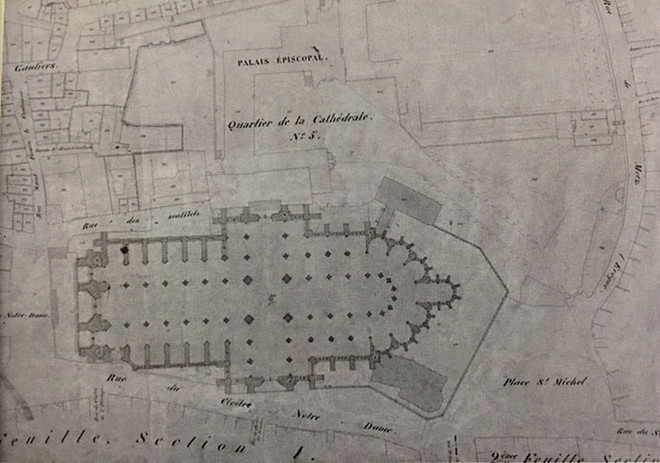

One can note in the plan of the building (Figure 5) the typical cruciform typology common in cathedral design. Not only does this signify the importance of religious symbolism, but the way the columns are arranged imply a processional linear order and a hierarchy of spaces with the altar at the head. What is also evident in the plan, is French lettering and annotations that represent the colonial perspective and the delineation of spaces that were deemed important or not. The Cathedral’s large footprint also sits in the middle of a busy intersection visually signifying the French colonial presence from all angles.

1. Filek-Gibson, Dana. Moon Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon). United States: Avalon Publishing, 2017.

5. Filek-Gibson, Dana. Moon Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon). United States: Avalon Publishing, 2017.

Reflection

In summary, the current Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Saigon (Figure 6) is a clear representation of the ways in which French colonists used religion to justify colonial acts. The development of Saigon was embedded with infrastructural reformations and architectural projects that reflected French interests abroad. The Roman Catholic church at the time was also responsible for the promotion of colonial actions and used colonialism to their advantage. The Cathedral exhibits characteristics that are common throughout international cathedrals, with prescribed hierarchies of spaces and religious symbolism. The location of the building also presents itself as a focal point within a public square. Whether the colonial conquest by the French in Indochina was successful is up for debate. However, given that Catholicism is the second most religion practiced under Buddhism in Vietnam, says something about their efforts. Ho Chi Minh City has developed rapidly over the years, however the legacy of French colonial architecture exists today.

Bibliography

Filek-Gibson, Dana. Moon Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon). United States: Avalon Publishing, 2017.

Kim, Annette M. “A History of Messiness: Order and Resilience on the Sidewalks of Ho Chi Minh City.” In Messy Urbanism: Understanding the “Other” Cities of Asia, edited by Chalana Manish and Hou Jeffrey, 22-39. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2016. Accessed April 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1d4tz9d.7.

Nguyen, Hung Thanh. “Buddhist-Catholic Relations in Ho Chi Minh City.” International Journal of Dharma Studies 5, no. 1 (2017): 1.

Njoh, Ambe J. “French Urbanism in Indochina.” In, 89-113. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015.

Vo, Nghia M.. Saigon: A History. Ukraine: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers, 2011.

Images

Figure 1: The Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Saigon – Elevation (1880)

Phú, Đình. “Nhà Thờ Đức Bà: Kiệt Tác Kiến Trúc 138 Năm Tuổi Giữa Sài Gòn.” Báo Thanh Niên. Báo Thanh Niên, April 4, 2018. https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/nha-tho-duc-ba-kiet-tac-kien-truc-138-nam-tuoi-giua-sai-gon-948869.html.

Figure 2: French Saigon Map Plan

Tim Doling, et al. “[Map] The Stories Behind Saigon’s French Colonial Street Names.” Saigoneer. Accessed April 24, 2021. https://saigoneer.com/old-saigon/8186-map-the-stories-behind-saigon-french-colonial-street-names.

Figure 3: Cathedral Stained Glass Windows

Phú, Đình. “Nhà Thờ Đức Bà: Kiệt Tác Kiến Trúc 138 Năm Tuổi Giữa Sài Gòn.” Báo Thanh Niên. Báo Thanh Niên, April 4, 2018. https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/nha-tho-duc-ba-kiet-tac-kien-truc-138-nam-tuoi-giua-sai-gon-948869.html.

Figure 4: Cathedral Nave

Phú, Đình. “Nhà Thờ Đức Bà: Kiệt Tác Kiến Trúc 138 Năm Tuổi Giữa Sài Gòn.” Báo Thanh Niên. Báo Thanh Niên, April 4, 2018. https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/nha-tho-duc-ba-kiet-tac-kien-truc-138-nam-tuoi-giua-sai-gon-948869.html.

Figure 5: Cathedral Plan

Phú, Đình. “Nhà Thờ Đức Bà: Kiệt Tác Kiến Trúc 138 Năm Tuổi Giữa Sài Gòn.” Báo Thanh Niên. Báo Thanh Niên, April 4, 2018. https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/nha-tho-duc-ba-kiet-tac-kien-truc-138-nam-tuoi-giua-sai-gon-948869.html.

Figure 6: The Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Saigon (Present)

Kalmusky, Katie. “Saigon Notre-Dame Basilica: Ho Chi Minh City’s Iconic Cathedral.” Culture Trip. The Culture Trip, June 15, 2018. https://theculturetrip.com/asia/vietnam/articles/saigon-notre-dame-basilica-a-guide-to-ho-chi-minh-citys-iconic-cathedral/.