A City Created By the Mills

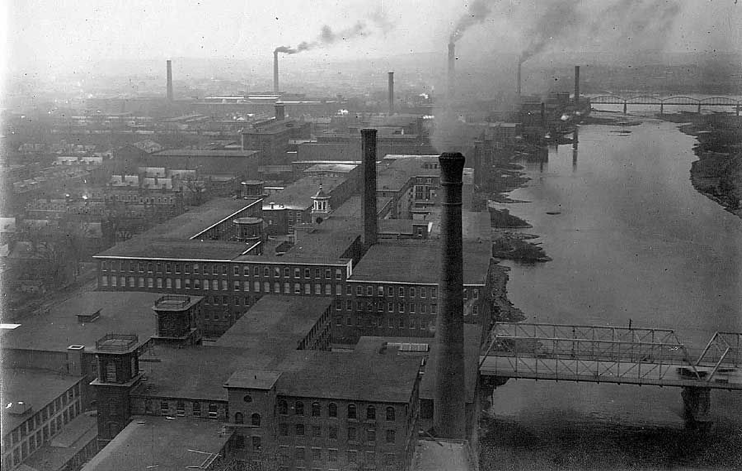

The Industrial Revolution was a change in human life circumstances that occurred in Britain, the United States, and Western Europe in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, owing in large part to developments in industrial technology. 1 Massachusetts became one of the wealthiest manufacturing centres in the nineteenth century as a result of its reliance on slavery. Lowell Mills introduced a new system of integrated manufacturing to the United States and established new patterns of employment and urban development that were soon replicated around New England and elsewhere. The Lowell mills were the first hint of the industrial revolution to come in the United States and they constituted some of the first paid labor outside domestic servitude available to women.1

1 Parker, Margaret Terrell. Essay. In Lowell: a Study of Industrial Development, 7–30. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1970.

How it started:

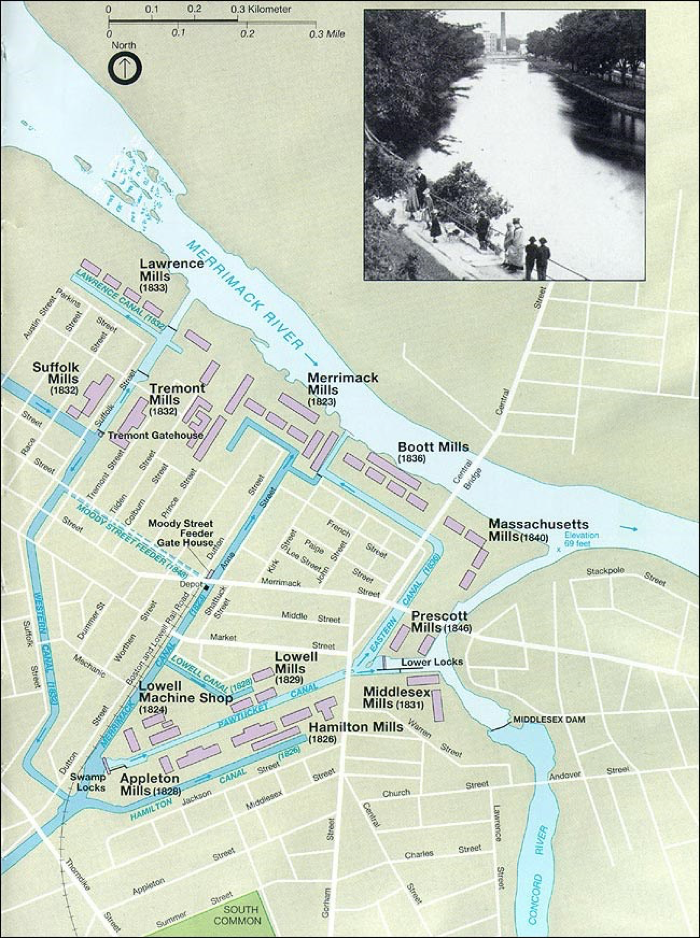

The Boston Manufacturing Company was founded by Francis Cabot Lowell in response to the increased demand for cloth during the War of 1812. Lowell went to Britain and was invited to tour British textile mills on site tours. The power looms used at these mills piqued Lowell’s interest. He was prohibited by English law from exporting mill models or designs that showed how the British produced their machinery and the method for turning raw materials into functional textiles. Lowell saw an opportunity to create a lucrative market back home in Massachusetts if such looms could be purchased and put into service. 2 At Waltham, Massachusetts, Lowell and his partners developed America’s first cotton-to-cloth textile mill. His associates founded America’s first planned factory town, which they named after him, after he died in 1817. 2 This company was funded by a public stock offering, which was one of the first in the United States. Lowell, Massachusetts, is known as the “Cradle of the American Industrial Revolution,” thanks to its 5.6 miles of canals and ten thousand horsepower delivered by the Merrimack River. 3 They designed the factory using cutting-edge technology that used water power to operate machines that turned raw cotton into finished cloth.4 Lowell hoped that embracing industrialism as a way of life would benefit the country both socially and economically.

2 Appleton, Nathan, and Samuel Batchelder. Essay. In The Early Development of the American Cotton Textile Industry Introduction of the Power Loom and Origin of Lowell, 20–67. New York: Harper & Row, 1969.

3 Dublin, Thomas. Essay. In Women at Work: the Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826-1860, 1–57. New York: ACLS History E-Book Project, 2005.

4 Loomis, Erik. Essay. In A History of America in Ten Strikes, 11–28. New York: The New Press, 2020.

Structure:

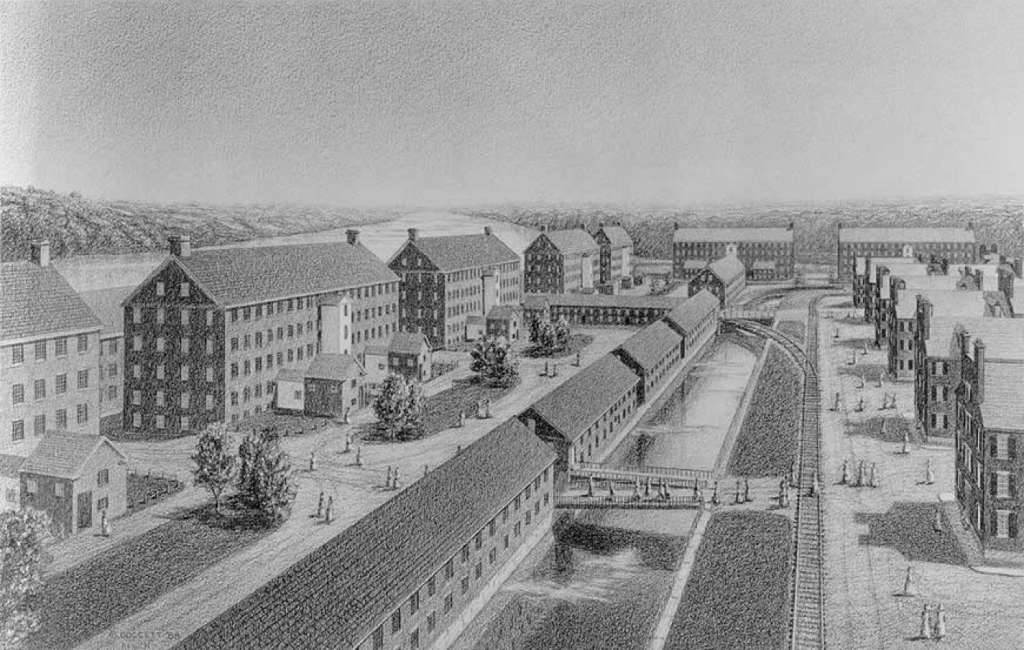

The mill in Waltham, Massachusetts, was the first vertically integrated factory in the United States, meaning that all fabric manufacturing activities were carried out under one roof. Mill towns modelled after Lowell sprung up all over New England, eventually forming the Waltham-Lowell system. 5 All of the machinery required to make cotton fabric from raw cotton was housed in large, redbrick, water-powered mills. The mills built boardinghouses for their employees, who were mostly native-born single daughters of Yankee farmers. The second mill, built in Waltham between 1816 and 1818, completed the development of the physical form, structural method, and building technique that would be used in Lowell later. The typical Waltham plan was rectangular, measuring 150′-160′ long by 40′-50′ wide, and was ideal for spaces that relied on natural light from outside windows. 6 A dormer-lit gable roof, brick construction with stone foundations, and a full-height exterior stair tower centered in one of the long elevations characterized the four floors of open floor space. 6 The aim was to take raw cotton and process it into bolts of functional cotton fabric, all while keeping it under one roof. This transition from small-scale manufacturing and outwork to large-scale machine manufacturing marked a new stage of capitalism in America. 5

5 “Building America’s Industrial Revolution: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts (Teaching with Historic Places) (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior.. https://www.nps.gov/articles/building-america-s-industrial-revolution-the-boott-cotton-mills-of-lowell-massachusetts-teaching-with-historic-places.htm.

6 Burnham, Edith E. “The economics of exploitation in antebellum New England: The life and death of Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, 1835-1905, 10–16. California State University, Dominguez Hills, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2007. 1456029.

The Boott Cotton Mills:

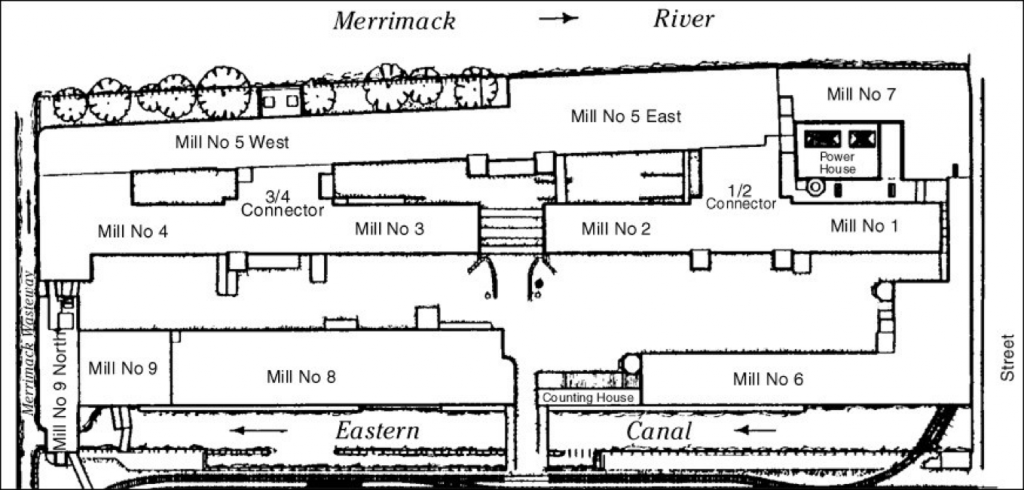

Four mills were constructed between 1836 and 1839 to house the Boott Cotton Mills company. On the mill yard side, the buildings were four floors tall, and on the river side, they were five stories tall. The four original Boott mill houses, were traditional Waltham mill structures. The mills were made of brick due to the abundance of clay in the area, though stonework was sometimes used due to the abundance of stone in the fields outside the mills. Each of the four-rectangular brick boxes had four stories, a dormer-lit attic, water wheels, and a cellar. Entry to the upper floors was created by stair towers centrally positioned on the exterior of each building. 7

The Boott Cotton Mills were one of many cotton textile mill complexes built in the growing city of Lowell, Massachusetts, between 1835 and 1910. The buildings of the Boott Cotton Mills were created as part of America’s first large-scale industrial planning initiative, and were designed by the same industrialists who built Lowell. Kirk Boott, the first agent of the initial textile company in Lowell, after whom the Boott Mills are named, was one of the planners. 8 The Boott millyard depicts the rise and fall of a single textile corporation during America’s early Industrial Revolution, as well as how it mirrored the rise and fall of the Northern textile industry. It was part of a larger industrial complex. It was only one component of a larger system, like every other system with several subsysteems and continued to operate for the next 50 years, but they never gained the same level of renown or profits as they had in the 1800s. With so many factors influencing the mills’ operations—World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, union organization, and tense labor-management relations—the Boott Mills was unable to stay afloat. Its doors slammed shut for good in 1954.

7 “Building America’s Industrial Revolution: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts (Teaching with Historic Places) (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/building-america-s-industrial-revolution-the-boott-cotton-mills-of-lowell-massachusetts-teaching-with-historic-places.htm.

8 Burnham, Edith E. “The economics of exploitation in antebellum New England: The life and death of Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, 1835-1905, 45–51. California State University, Dominguez Hills, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2007. 1456029.

Lowell Girls:

For young women, the Lowell mills were seen as a utopian society. Lowell chose to stop using child labor, which was popular in England’s cloth mills, since the factory required jobs. Since the job was not physically demanding, the staff did not need to be physically fit. The workers, on the other hand, had to be reasonably knowledgeable in order to master the complex machinery. Young women were hired as a remedy. 9 Women were chosen as millworkers in part because men were too expensive to employ and children couldn’t operate the modern complicated machinery. Women employees would be half the price of men, and a female workforce would provide the world with an image of moral and orderly factory life. These mills employed girls between the ages of 15 and 25, with the expectation of working for a limited period of time, normally 1-3 years. There were typically 80 women working at machines in each office, with two male supervisors overseeing the process. 10 The employment of women in factories was groundbreaking to the point of revolution where the young women were housed in an area that was not only secure but also reputed to be culturally favorable. 9 The women worked for themselves, lived in comfortable and clean quarters, and were motivated by education. 10 When not working, the women were encouraged to pursue educational goals, and they also contributed articles to a journal called The Lowell Offering. 11 In addition, the company established boardinghouses to provide secure living quarters for female workers, as well as enforcing a strict moral code. However, as the “factory system” grew in sophistication, many women entered the wider American labor movement to oppose harsher working conditions. The Lowell Offering, a journal for, by, and about mill workers, was born out of this desire for education and the desire to become social activists. This magazine enabled women to express themselves about their work, lives, and feelings in a way that was appropriate for the mid-nineteenth century. 10

9 Abbott, Edith. “History of the Employment of Women in the American Cotton Mills: II.” Journal of Political Economy 16, no. 10 (1908): 680–92. https://doi.org/10.1086/251480.

10 Hager, Christopher. “Lowell Mill Girls: Women’s Work and Writing in the Early Nineteenth Century.” A History of American Working-Class Literature, n.d., 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316216439.005.

11 Montrie, Chad. “’I Think Less of the Factory than of My Native Dell’: Labor, Nature, and the Lowell ‘Mill Girls’.” Environmental History 9, no. 2 (2004): 275. https://doi.org/10.2307/3986087.

Bibliography

Abbott, Edith. “History of the Employment of Women in the American Cotton Mills: II.” Journal of Political Economy 16, no. 10 (1908): 680–92. https://doi.org/10.1086/251480.

Appleton, Nathan, and Samuel Batchelder. Essay. In The Early Development of the American Cotton Textile Industry Introduction of the Power Loom and Origin of Lowell, 20–67. New York: Harper & Row, 1969.

“Building America’s Industrial Revolution: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts (Teaching with Historic Places) (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/building-america-s-industrial-revolution-the-boott-cotton-mills-of-lowell-massachusetts-teaching-with-historic-places.htm.

Burnham, Edith E. “The economics of exploitation in antebellum New England: The life and death of Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, 1835-1905, 10–16. California State University, Dominguez Hills, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2007. 1456029.

Coles, Nicholas, and Paul Lauter. A History of American Working-Class Literature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Dublin, Thomas. Essay. In Women at Work: the Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826-1860, 1–57. New York: ACLS History E-Book Project, 2005.

Hager, Christopher. “Lowell Mill Girls: Women’s Work and Writing in the Early Nineteenth Century.” A History of American Working-Class Literature, n.d., 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316216439.005.

Loomis, Erik. Essay. In A History of America in Ten Strikes, 11–28. New York: The New Press, 2020.

Montrie, Chad. “’I Think Less of the Factory than of My Native Dell’: Labor, Nature, and the Lowell ‘Mill Girls’.” Environmental History 9, no. 2 (2004): 275. https://doi.org/10.2307/3986087.

Parker, Margaret Terrell. Essay. In Lowell: a Study of Industrial Development, 7–30. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1970.

Images

Fig. 1: “The Merrimack River.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/lowe/learn/historyculture/the-merrimack-river.htm.

Fig. 2: “Building America’s Industrial Revolution: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts (Teaching with Historic Places) (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/building-america-s-industrial-revolution-the-boott-cotton-mills-of-lowell-massachusetts-teaching-with-historic-places.htm.

Fig. 3: “Building America’s Industrial Revolution: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts (Teaching with Historic Places) (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/building-america-s-industrial-revolution-the-boott-cotton-mills-of-lowell-massachusetts-teaching-with-historic-places.htm.

Fig. 4: “Building America’s Industrial Revolution: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts (Teaching with Historic Places) (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/building-america-s-industrial-revolution-the-boott-cotton-mills-of-lowell-massachusetts-teaching-with-historic-places.htm.

Fig. 5: Harris, Karen. “Lowell Girls: The 1st Female Workers To Form A Union.” History Daily, May 29, 2019. https://historydaily.org/who-were-lowell-girls.