The Egyptian Revival Style enjoyed attention in the United States (US) as “an exotic” and as a primarily architectural phenomenon in the mid-nineteenth century.1 Architectural markers from the time—such as the original Library of Congress (1808), and the Washington monument (1848)—point to the problematic nature of colonial power exerting influence through the fetishization of ancient cultures. In nineteenth century America, colonial exertions of power were heavily entrenched on a White, euro-descendant assertion of racial superiority over ‘inferior’ races, contextually referring to Black enslaved peoples. I will explore how in nineteenth century America, this exertion of power was channelled partially by the “conscription of Egyptian imagery into the services of empire [and] authority” and employed rhetorically as a means of self-providence in defining the US as a White, euro-descendeant, enslaved-persons-owning nation.2 In particular, I will use the Egyptian Building of 1848 (home of the Faculty of Medicine) on the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) campus, its facades, and its symbols, as a means for spatial analyses of the embodiment of the contemporary, acontextual Egyptomania and pseudo-scientific themes in medical education at the time used to promote, and justify the colonial, social, and empirical ambitions of the US in the mid-nineteenth century.3

Prior exploring how exactly the Egyptian Building acts as a marker for the broader assertion of empire and racial ‘superiority’ in the US, it’s necessary to address both themes in isolation to establish a better contextual understanding; that is: the role of Egyptomania in the US at large during the nineteenth century; and the historical intersections of race, and medicine as a means of segregation in the US. In “Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-Century American Egyptomania”, Clayton posits that “throughout American history the iconography of empire—that of its wielders as well as its resisters—was lavishly drawn from that of ancient Egypt.”4 Looking in during the mid-nineteenth century, we see that the US (particularly the south) was still actively involved in all systemic forms chattel slavery. Therefore the appropriations of what was “history’s […] most infamous slave societies” is not only coincidental, but a purposeful move by the US as establishing itself racially, socially, and culturally, as a global leader of civilization.5 Similarly, the period of completion of The Egyptian Building in the 1840s, as well as the fact it was the architectural vessel for the faculty of medicine at VCU makes the systemic racism within the medical field of nineteenth century America poignantly relevant. By the nineteenth century, “racially oriented European pseudoscientific data […] was being used in the U.S. to justify and defend black slavery” and help create a “racial mythology” that equally justified the perceived racial ‘purity’ of the White race.6 Thus, as it relates to The Egyptian Building, one can see how its role of housing a medical school in the American South in the 1840s further points to it as an architectural space where (White) young European and American physicians were “prominent participants in the barbaric Atlantic slave trade and brutal New World slave health systems.”7

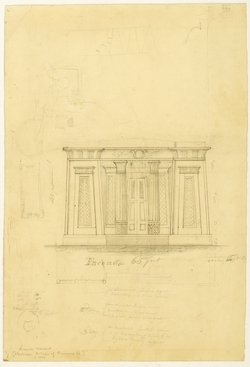

With this context in mind, I will now go from the broader scale of the exterior facades, down to the very narrow lens of symbols and icons of The Egyptian Building to reveal how it combined the Egyptomania and racial medical pedagogy as a symbol of White euro-descendant assertions of power. Completed 1848 by Greek Revival architect Thomas Stewart, it was commissioned to house the Medical College of Virginia (later to be integrated to the VCU) and remains as “the oldest medical college building in the South”.8 As seen in Fig. 1, an original elevation by the architect, the Egyptian replica style is immediately evident from the temple-like form and symmetry. Of particular note are the two ornamental palm capital columns visible in Figures 2 & 3, especially given that it uses the move of creating a visibly heavy, authoritative exterior form.9 A lack of windows at the entrance, as seen in Figs 1 & 2 further adds to this temple-like aesthetic, indicating something of great value is hidden beyond the doors and thus building this notion of eminence and cultural refinement. This architectural language of weight, mass, and authority reveals how the use of pseudo-Egyptian forms is merely a contextless, blatant misappropriation and twisted sense of ownership of ‘culture’ by powerful White American elites who wanted to convey said notions power—be it social, racial, or economic.

This orientalist appropriation is made more apparent seeing the snow surrounding the building in Figure 2, where one is reminded that it is located in Richmond, Virginia and is so far removed from Egypt spatially and chronologically that its placement could be considered nothing more than a brash, orientalist self-indulgence not at all different to the Chinese Pavilions that populated English gardens seen earlier in our term. Consequently, it is the quixotic nature of The Egyptian Building’s overtly monumental exterior, as well as its completely ahistorical relationship with the landscape it sits on, that would be used by White Southern elites to promote their agenda, which included “pseudoscientific racist principles, derogatory racial character references, and pronouncements of impending black racial extinction.”10

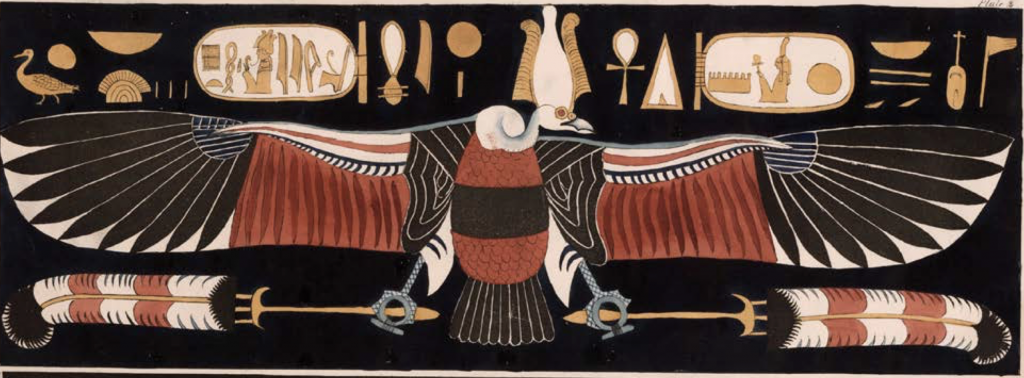

associated with themes of divinity, death, and divinity.

As is custom, the Vulture is clasping the Shen in each claw, another glyph of the divine right. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/547abd24e4b0780d55c0bb4a/t/5c6ab4b1eef1a1de5b15c1c2/1550496959640/Nile+Magazine+10%2C+Oct-Nov+2017%2C+Noble+Vulture-R.pdf

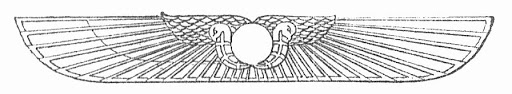

However, it is not only in the form of The Egyptian Building, but its plastering of Ancient religious and cultural Egyptian symbols on the exterior and (far more generously) in its interior that contributed to this effect. Their role is not merely aesthetic, but truly as a subtext to themes of the ‘racial mythology’ of Whiteness being construed in the US, and in medical education, since before its independence.11 Starting with the exterior, we can see in Figure 2 that depicted along the top of the entrance are three instances of The Egyptian Winged Disk, “a royal icon of divine kingship” and the God Horus that later went on to appear near current day Syria.12 Given the symbol’s repetition, the move seems quite purposeful and so it indicates that its intention was to subliminally evoke these notions of divinity, of power, and influence (See fig. 4). As seen in Fig. 5, the interior carries these motifs even further. At a first glance, we see a flying vulture splayed above a doorway. A highly significant symbol in Ancient Egypt, it is usually depicted in tombs and temples, clutching in each leg the Shen (see Fig. 6 & 7), yet another symbol that refers to eternal protection and divine right.13 Just below it is perhaps one of the most commonly recognizable symbols, the Ankh, which “symbolizes divinity, resurrection, and immortality in eternal life” (see Fig. 8).14 Thus, these themes of divinity, immortality, and authority though implicit and wildly out of context, are an architectural marker which promoted the dialogues of racial superiority, power, and of self-providence as a burgeoning civilization.

The link between the idea of appropriating Ancient Egyptian forms and symbols as a means of promoting a racist, eugenicist agenda in the US is as convoluted as it is rich. Nevertheless, it is imperative to acknowledge the limitations that this paper faces, and shortcomings it does not pretend to overlook. Firstly, Chattel slavery is mentioned passingly in this exploration, and is a topic that requires a far deeper exploration in order to fully comprehend its ramifications, and this much is true particularly as to how it relates to healthcare and medicine in the US. Secondly, whilst certain symbols and their meanings are explored in this paper, many are not and understanding them fully is similarly a task that requires far more than the scope it is limited to in this paper, which in no way can hope to address over three millennia of Ancient Egyptian culture. Nevertheless, it is the intention behind the use of such symbols, as well as the forms reminiscent of Ancient Egyptian culture that reveals an implicitly racist, orientalist attempt to promote certain dialogues of colonial superiority by White euro-descendant Americans evident with the construction of The Egyptian Building. As explored throughout this paper, this firstly given the Building’s exterior form and massing, as its temple-like associations of authority and strength strongly convey a twisted sense of the “racial myth” of White superiority whilst employing Egyptian motifs. Finally, select ancient religious symbols on the exterior, and primarily on the interior, strongly allude to ideas of divinity and providence that further highlight how The Egyptian Building promotes an agenda of White racial superiority.

1 “National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form.” United States Department of the Interior National Parks Service, April 16, 1969. 4; Ickow, Sara. metmuseum.org. Egyptian Revival. The Met, July 2012. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/erev/hd_erev.htm

2 Trafton, Scott. Essay. In Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-Century American Egyptomania, 39. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005. https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/928/Egypt-LandRace-and-Nineteenth-Century-American, 4.

3 “National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form.”

4 Trafton, Scott. Essay. In Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-Century American Egyptomania, 2.

5 Ibid

6 Byrd, Michael, and Linda A Clayton. “RACE, MEDICINE, AND HEALTH CARE IN THE UNITED STATES: A HISTORICAL SURVEY”. Journal of the National Medical Association 93, no. 3 (March 2001): 11-44, 18.

7 Ibid, 19

8 “National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form.”, 4.

9 Hoke, Thelma Vaine. The First 125 Years, 1838-1963. Virginia Commonwealth University 61. Vol. 61. Richmond, Virginia: Medical College of Virginia, 1963. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/vcu_books/2/.

10 Byrd, Michael, and Linda A Clayton. “RACE, MEDICINE, AND HEALTH CARE IN THE UNITED STATES: A HISTORICAL SURVEY”, 19.

11 Ibid

12 Sara Pizzimenti, “Adaptation of the Winged Disk in the Old Syrian Glyptic: A Study of Cultural Interaction in the Eastern Mediterranean,” in DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀCONTRIBUTI E MATERIALIDI ARCHEOLOGIA ORIENTALEXVIII(2018 (Rome: Scienze e Lettere, 2018), pp. 521-538.

13 Jackson, Lesley. “The Noble Vulture.” The Nile Magazine. The Nile Magazine, October 2017. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/547abd24e4b0780d55c0bb4a/t/5c6ab4b1eef1a1de5b15c1c2/1550496959640/Nile+Magazine+10%2C+Oct-Nov+2017%2C+Noble+Vulture-R.pdf

14 Michael, Vivian S. “The Pharaonic Sign ‘Ankh’ between History and Modern Fashion.” International Design Journal 8, no. 4 (October 2018). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327967972_The_Pharaonic_sign_Ankh_between_history_and_modern_fashion.

Bibliography:

Byrd, Michael, and Linda A Clayton. “RACE, MEDICINE, AND HEALTH CARE IN THE UNITED STATES: A HISTORICAL SURVEY”. Journal of the National Medical Association 93, no. 3 (March 2001): 11-44.

Hoke, Thelma Vaine. The First 125 Years, 1838-1963. Virginia Commonwealth University 61. Vol. 61. Richmond, Virginia: Medical College of Virginia, 1963. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/vcu_books/2/

Ickow, Sara. metmuseum.org. Egyptian Revival. The Met, July 2012. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/erev/hd_erev.htm

Jackson, Lesley. “The Noble Vulture.” The Nile Magazine. The Nile Magazine, October 2017. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/547abd24e4b0780d55c0bb4a/t/5c6ab4b1eef1a1de5b15c1c2/1550496959640/Nile+Magazine+10%2C+Oct-Nov+2017%2C+Noble+Vulture-R.pdf

Michael, Vivian S. “The Pharaonic Sign ‘Ankh’ between History and Modern Fashion.” International Design Journal 8, no. 4 (October 2018). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327967972_The_Pharaonic_sign_Ankh_between_history_and_modern_fashion

“National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form.” United States Department of the Interior National Parks Service, April 16, 1969.

Sara Pizzimenti, “Adaptation of the Winged Disk in the Old Syrian Glyptic: A Study of Cultural Interaction in the Eastern Mediterranean,” in DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE DELL’ANTICHITÀCONTRIBUTI E MATERIALIDI ARCHEOLOGIA ORIENTALEXVIII, 2018 (Rome: Scienze e Lettere, 2018), pp. 521-538.

Trafton, Scott. Essay. In Egypt Land: Race and Nineteenth-Century American Egyptomania, 39. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005. https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/928/Egypt-LandRace-and-Nineteenth-Century-American