Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GooderhamAndWorts1800s.jpg

Every Christmas, Torontonians flock to the distillery district to shop under twinkling lights as they stroll down old brick roads lined by preserved heritage buildings that have been adaptively reused. Designated as a heritage neighborhood based upon, “illustrating the entire distillery process, from the processing of raw materials, to the storage of finished products for export; the physical evidence that it provides about the history of Canadian business, the distilling industry and 19th-century manufacturing processes; the architectural cohesiveness of the site characterized by a high degree of conformity in the design, construction and craftsmanship of its constituent buildings; and the physical relationships among the buildings and between the site and the railway to the south”[1], the Gooderham and Worts Distillery district is more than a great Instagram background. The streets and buildings that define this neighbourhood reflect an era that cemented Toronto and Canada as a settler colonialist country.

In the late 1800s, Gooderham and Worts was the largest distiller of spirits in the British Empire. Their distilling compound was woven into the physical and economic fabric of British North America and the British colonialist network. Its establishment by British emigrants is a distinct settler narrative. Its role as a leader in capitalist industrialization reinforced structures of settler colonialism through its site and location, and architecture.

Site and Location:

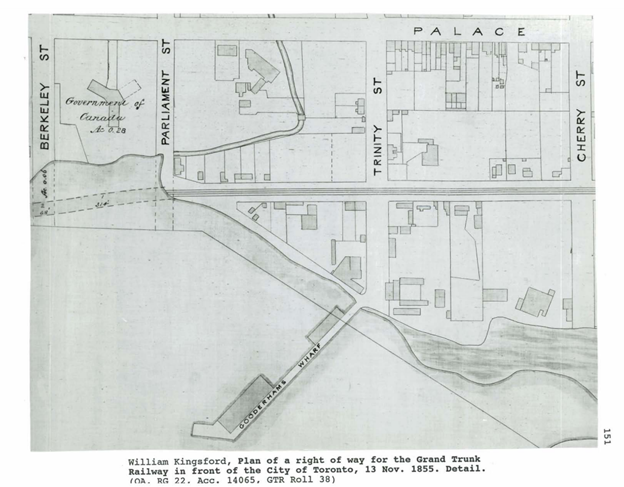

Gooderham and Worts was established along the original shoreline of Lake Ontario, in the east portion of the region of York, which is modern-day Toronto. It was bisected by the Grand Trunk Railway[2], which ran from Montreal to Portland through York[3]. South of the railroad tracks was the Gooderham Wharf used for shipments. The compound used a combination of streets and lanes[4] to create a hierarchy of buildings and promote circulation.

The distilleries physical infrastructure supported and benefited from the growth of York. Paralleling the establishment of York as the capital city of Lower Canada[5], Gooderham and Worts rose as a leader in distilling spirits. York was an important customer for the distillery, which not only supplied spirits to the city but also, waste products. A pipeline along the railway tracks conveyed slop from the whiskey production to a city tap for livestock along with their cattle[6]. They also used the slag from the coal to line the streets.[7]

The railway provided access to a larger market, and Gooderham and Worts, in turn, was the Grand Trunk Railway’s biggest client. The distillery utilized its railway adjacency in sourcing materials for construction and raw products for its spirit production. They had a private switch for fourteen train cars to review the product directly to the first building in the production line[8]. They sourced their ‘Indian corn’ from the United States via the railway and exported their spirits to New York and Montreal for distribution worldwide.

Gooderham and Worts sourced most of its grain from Kingston, across Lake Ontario, utilizing its private wharf. The wharf served as a connection to Great Britain and regional materials, which supported the distribution of whiskey across the British Empire, further strengthening British colonial rule globally by providing capital through taxation.

The distillery supported the physical distribution networks that ensured North American continental settlement through its location at the intersection of ports and railways at the edge of a future city.

Architecture:

The Victorian architecture of the over 40 brick and stone buildings that formed the distillery compound were purpose-built structures that functioned as a distillation production line. From the stone distilleries to the cooperage, the maltings building to the pure spirit buildings, each served as a step in the process. Their forms responded to their use while maintaining neoclassical details and utilizing locally extracted materials.[9] Together, they communicated York’s production power in an industrial age by their scale and composition.

The facades of the buildings represent Canadian resource extraction. The brick was formed from local clay at brickworks which became symbolic of Toronto’s heritage architecture[10]. The stone was limestone mined in Kingston and shipped to the private wharf.[11] The structures were a combination of iron and wood. These materials supported the growing extraction economy, which established Canada and remains a conflict with indigenous communities today.

The use of neoclassical detailing with the coupla, arched windows, and copper detailing is a nod to York’s colonial heritage. The architect, David Roberts, was commended for this innovation in integrating engineering in the buildings. He designed mechanical production line-style systems that reduced human interaction with the product and connected the buildings. The structures were made to last with oversized walls and exteriorized columns and beams separated from the walls for beam replacement if timber failed[12]. Additionally, he included more glazing for daylighting the space while also serving as blow-out windows in case of fire. This style was praised for “keeping pace with the march of the times” while providing credit to York architecture as a cultural leader in North America.[13]

Conclusion

Since its establishment to its new life today, the Gooderham and Worts distillery has been praised for its ability to show the process of distilling spirits to the public. It has been highlighted as an important cultural and architectural landmark, from its role in North American industrialization to its red brick found off the banks of the Don Valley. Within these heritage classifications’ places are recognized for their role in establishing our country; however, inherent in these determinations is also the colonialism and ongoing settler colonialism required to stand on these lands today. The famous red brick was extracted from lands that were divided and sold often without indigenous consent. Industrialization supported a capitalist system that often displaces in the pursuit of greater efficiency and capital. The railroads and shipping lanes that helped spread the spirits across the continent and globe also became the justification for stealing lands and furthering colonialist rule. Simultaneously, understanding how a place is beautiful and essential while also contributed to systemic issues that often outlive the walls of the building that helped build them need not diminish the value of heritage but rather provide a richer, more complex way to understand how interconnected our decisions and places genuinely are.

[1] Parliament. “Gooderham and Worts Distillery National Historic Site of Canada.” Parcs Canada. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=539.

[2] The Globe, February 7, 1862, pl “Annual Review of the Trade of Toronto for 1861: Distillery of Messr Gooderham & Worts”

[3] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Portland.” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 18, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/place/Portland-Maine.

[4] Parks Canada. “HistoricPlaces.ca – HistoricPlaces.ca.” Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=1195.

[5] Parliament. “Gooderham and Worts Distillery National Historic Site of Canada.” Parcs Canada. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=539.

[6] Otto, Stephen. “Gooderham and Worst Hertigae Plan Report Number 4.” Distillery District Heritage Website, 1994. http://distilleryheritage.com/report_4.html.

[7] The Mail [Toronto], April 23, 1872

[8] The Globe, February 7, 1862, pl “Annual Review of the Trade of Toronto for 1861: Distillery of Messr Gooderham & Worts”

[9] Victorian Industrial Architecture at the Distillery District” Distillery District Heritage Website, 1994. http://distilleryheritage.com/PDFs/buildings/victorian.pdf

[10] “STREET ARCHITECTURE: THE BUILDING TRADE IN TORONTO NEW WHOLESALE WAREHOUSE FOR MESSPS. JOHN MACDONALD & CO. SECOND CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH MISSES. RICE LEWIS A SON’S NEW STORE QUEEN’S HOTEL NEW MALT HOUCE, &C., FOR MESSRS. GOODERHAM & WORTS ADDITIONS TO MR. ALDWBIL’S BREWERY, WILLIAM STREET.” 1863.The globe (1844-1936), Mar 26, 2. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/historical-newspapers/street-architecture/docview/1516471514/se-2?accountid=14656.

[11] The Globe, February 7, 1862, pl “Annual Review of the Trade of Toronto for 1861: Distillery of Messr Gooderham & Worts”

[12] Parliament. “Gooderham and Worts Distillery National Historic Site of Canada.” Parcs Canada. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=539.

[13] “STREET ARCHITECTURE: THE BUILDING TRADE IN TORONTO NEW WHOLESALE WAREHOUSE FOR MESSPS. JOHN MACDONALD & CO. SECOND CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH MISSES. RICE LEWIS A SON’S NEW STORE QUEEN’S HOTEL NEW MALT HOUCE, &C., FOR MESSRS. GOODERHAM & WORTS ADDITIONS TO MR. ALDWBIL’S BREWERY, WILLIAM STREET.” 1863.The globe (1844-1936), Mar 26, 2. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/historical-newspapers/street-architecture/docview/1516471514/se-2?accountid=14656.

Bibliography

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Portland.” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 18, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/place/Portland-Maine.

Otto, Stephen. “Gooderham and Worst Hertigae Plan Report Number 4.” Distillery District Heritage Website, 1994. http://distilleryheritage.com/report_4.html.

Otto, Stephen “Victorian Industrial Architecture at the Distillery District” Distillery District Heritage Website, 1994. http://distilleryheritage.com/PDFs/buildings/victorian.pdf

Parliament. “Gooderham and Worts Distillery National Historic Site of Canada.” Parcs Canada. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=539.

Parks Canada. “HistoricPlaces.ca – HistoricPlaces.ca.” Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=1195.

The Globe, “Annual Review of the Trade of Toronto for 1861: Distillery of Messr Gooderham & Worts. February 7, 1862

The Globe, “STREET ARCHITECTURE: THE BUILDING TRADE IN TORONTO NEW WHOLESALE WAREHOUSE FOR MESSPS. JOHN MACDONALD & CO. SECOND CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH MISSES. RICE LEWIS A SON’S NEW STORE QUEEN’S HOTEL NEW MALT HOUCE, &C., FOR MESSRS. GOODERHAM & WORTS ADDITIONS TO MR. ALDWBIL’S BREWERY, WILLIAM STREET.” 1863.The globe (1844-1936), Mar 26, 2. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/historical-newspapers/street-architecture/docview/1516471514/se-2?accountid=14656.