Introduction

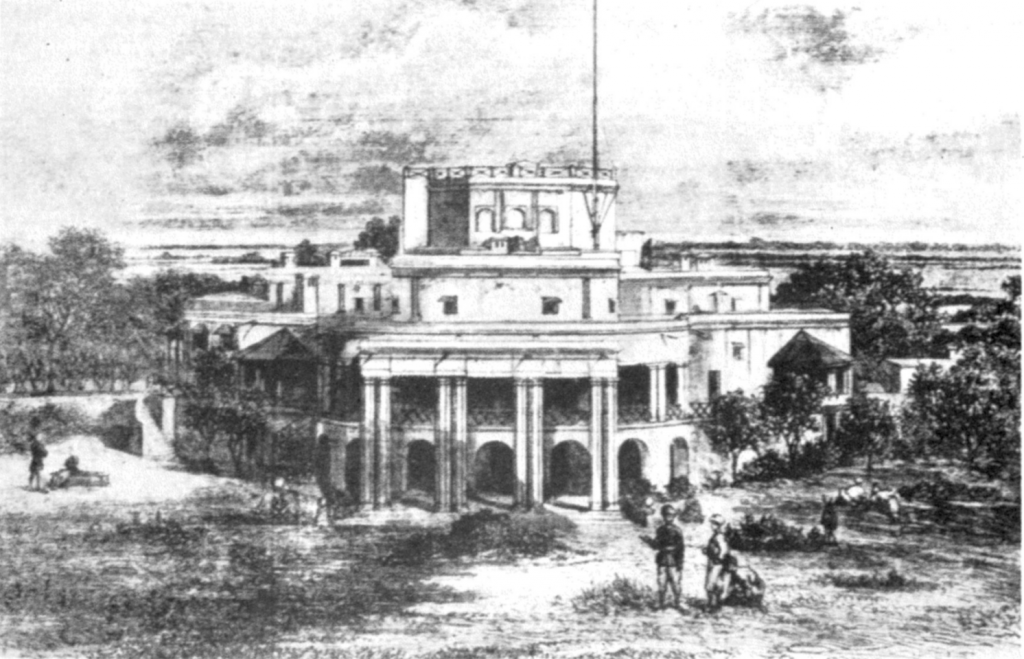

The stratified construction of Qasim Khan’s tomb, into the Governor’s House at Lahore, Punjab, echoes the broader colonial system of maintaining difference between the ruler and the ruled through the process of building in the Indo-Saracenic style. While the common post-colonial reading of the Indo-Saracenic style has been often interpreted as a political strategy to legitimize the British Raj as the successor of the Mughal empire by integrating Western and Indian architectural styles, it simultaneously devalues the role of the “mistri,” or native builder and architect1. Despite arguments that the “style” lacked authenticity or failed to recreate historically accurate Mughal architecture2, the involvement of locally trained craftsmen, engineers, and architects afforded them opportunities in constructing identity amidst this tumultuous period. By adapting and transforming the Mughal nobleman’s tomb into a “great Edwardian mansion,” 3 the British permeated India’s urban landscape in the domestic realm as an act of appropriation and assimilation (Fig 1.0). Yet, as the house continues to be part of a well-preserved multitude of colonial public buildings in Lahore, it reflects the significance of architectural hybridity as a process of empire-building and identity-forming. Hence, the collective survival of these public buildings destabilizes the view that Indo-Saracenic architecture was the sole intellectual product of British architects, but rather a much more complicated collaborative process of colonial convergence.

Background

Located at a major crossing on the Ravi River, Lahore was considered a metropolis amoung the four Imperial centers of Mughal India. 4 Long before the period of British occupation, Lahore served as the provincial capital of Punjab and established its history of both strategic and commercial importance. As one of the last major cities to be brought under British control in the nineteenth century, Lahore was already a hybridized environment of inhabitants from various religious and cultural backgrounds. When Europeans first encountered the city after years of war between the Sikh and Mughal Empires, the relics and monuments of the landscape were described as “waste and desolate” 5 by travelers and local historians alike.

As the British military occupation of the city began in the nineteenth century, specific buildings and sites were strategically chosen for their adaptive reuse. The tomb of Qasim Khan and the land surrounding it are rendered as such a site, initially occupied by Sikh rulers before the assimilation by British officials in the mid-nineteenth century. To the British, living in a Mughal tomb was seen as justified, “as a means of saving endangered or derelict buildings” 6 and it was not unusual for tombs to be turned into dwellings. 7

Architectural Form and Meaning

The Governor’s House served a highly public and political function of the British administration and was built to convey colonial authority through the so-called Indo-Saracenic style. Dressed in the “official new colonial building style, [it] give[s] an illusion of traditional authority and continuity between the Mughal, Sikh, and British empires…to help validate the latest colonial administration.” 8 In order to establish themselves as the seemingly legitimate successors to the Mughals, the hybrid form of classical European style and mastery over Indic detail was produced. Additionally, when the British chose a Mughal tomb as the site for their bureaucratic power, it subsequently created a hybrid house within the already layered landscape.

Understanding the importance of spatial hierarchy as part of the public presence, the British “maintain[ed] control of all of India…through visual control in the landscape.”9 Yet, in the attempt to create a unified style that portrayed the British as “indigenous” rulers, the resulting “hybrid architecture would be seen as a reflection of their contradictory reality.” 10 This separation reinforced the difference between ruler and the ruled, assuring the British who used or worked in these hybrid spaces that they were not actually hybrid subjects11.

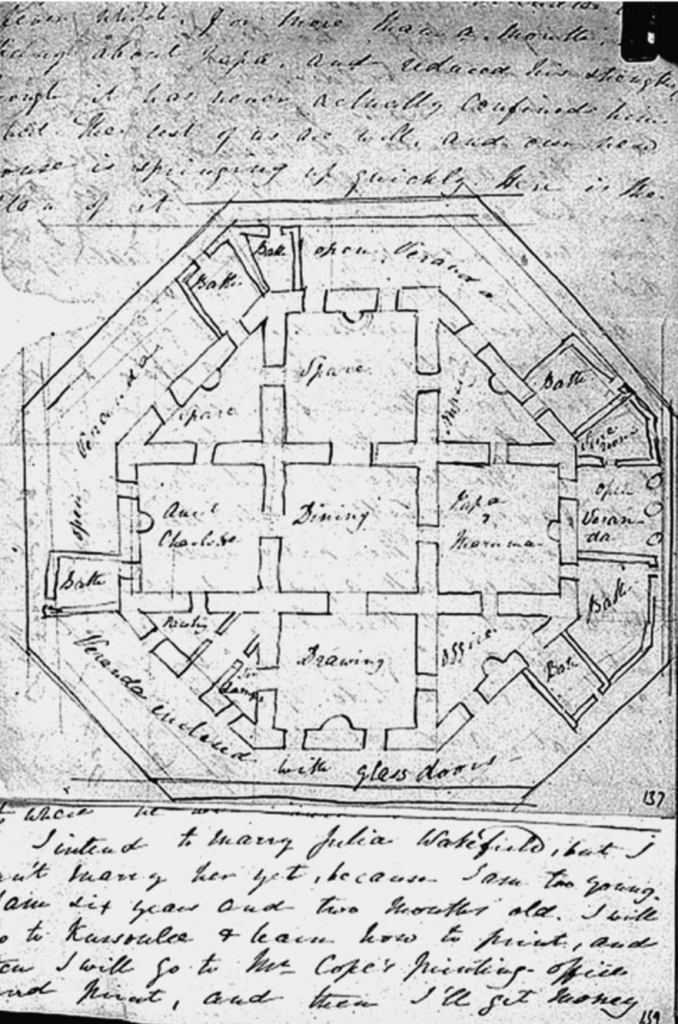

In the early spring of 1851, the conversion of the tomb into a permanent house was underway for a senior British official named Henry Lawrence. The Baghadadi octagon of the tomb served as the foundational plan of the home, where the house stands on a chabutra, or raised platform about twelve foot high12. Despite the additions and remodelling of the house throughout the British occupation, the survival and centrality of Kasim Khan’s tomb can be seen as evidence for the changing phases of assimilation and hybridity. The octagon consisted of four spacious rooms adjacent to the four sides of the tomb, four smaller rooms of a triangular shape, and surrounded by an outer octagon of verandahs and bathrooms (Fig 2.0). In the very center of the house was the dining room, which was built directly on top of the tomb. It has been designed to be a “high, domed chamber in the Moghul style, decorated with niches and arabesques.” 13 An account of the house’s interior has been described as “a regular hybrid: one side of the principle front had verandahs with pointed Gothic arches, the other side Classical, while the center was in the massive but unassuming style of an old Punjab officer’s mess.” 14

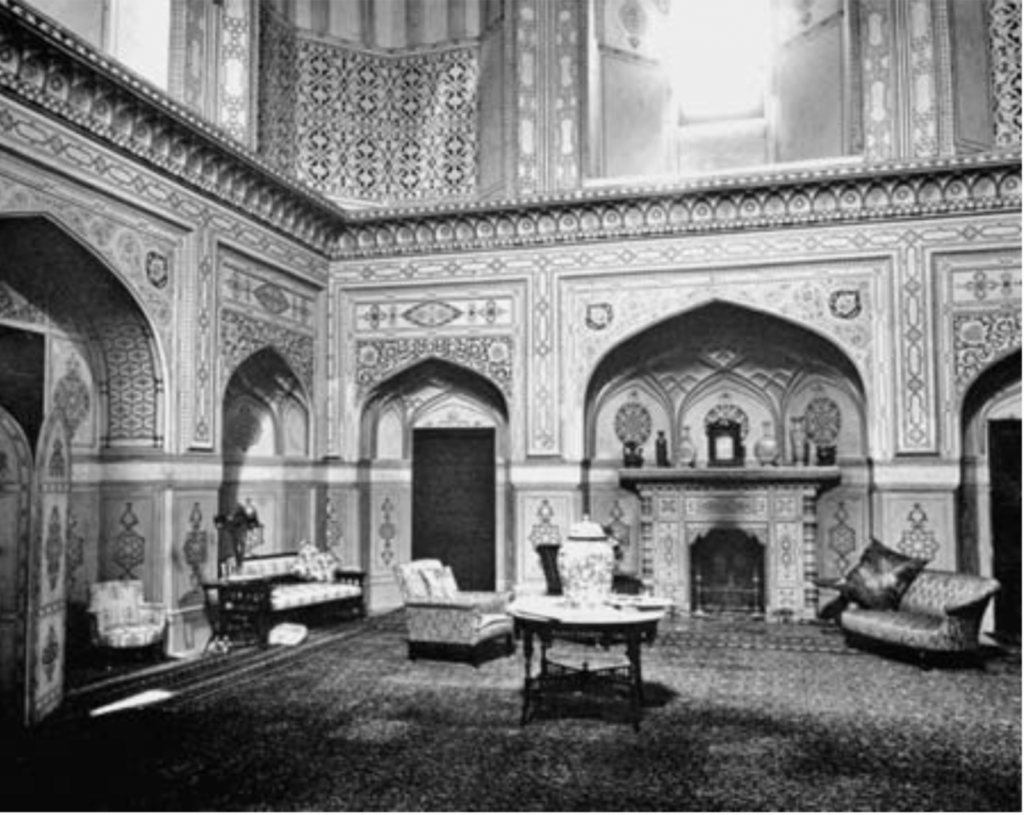

This continuum of hybridity in adapting buildings involved what the British claimed as “rescuing” in the restoration of the tomb 15. Sometime between 1851 and 1876, the central tomb was significantly decorated and repainted in full colour (Fig 3.0) by the students of Lahore’s Mayo School of Art in the effort to help sustain unbroken traditions of Indian art. John Lockwood Kipling, principal of the school, attempted to remedy the negligence of indigenous architecture and design throughout his lifetime. Such instances can be found in the dining room of the Governor’s House, where it replicated the arabesques of other Indian monuments. Yet to an extent, these efforts represented a British view of what Mughal decoration should be like. Further additions were made in 1892, where the south wing with Gothic verandahs was lengthened in a “pan-orientalizing Moorish taste” 16, designed once again by Kipling. As the halls were enlarged and doubled in size, the tomb chamber continued to stand at the center of the structure and avoided demolition.

Conclusion

While the construction and expansion of the Governor’s House represented a form of colonial power in its Indo-Saracenic style, the notion of hybridity inherent in the building is also “the locus where both colonizer and colonized elements engage and transform each other” 17. At the material level, the design and physical construction of Lahore’s buildings are neither wholly British or Indian, but also indisputably both. This can be seen as part of the collective preservation of Lahore’s public buildings, which reflects the layering of the city’s urbanism through the different occupational periods of its history (Fig 4.0). Critics suggest that Lahore was a place of the imagination where urban architecture was built piecemeal, creating a hybrid model that was a distinctive social and cultural milieu. The transformed urbanism of this layered landscape was a “colonial collaborative project in which both the British overlords and Indian subjects participated in creating a new ‘social imagination.” 18 Today, the building continues to hold significant political and cultural meaning, where it has been designated for the formal use of the Punjab’s Governor.

Notes:

1 Chopra, Preeti. “Anglo-Indian Architecture and the Meaning of Its Styles” p. 31

2 Bryant, Julius. “Colonial Architecture in Lahore: J. L. Kipling and the ‘Indo-saracenic’ Styles.” p. 62

3 Shorto, Sylvia. “A Tomb of One’s Own: The Governor’s House, Lahore.” p. 151

4 Ibid. p. 154

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid p. 159

7 Bence-Jones, Mark. “Government House Lahore.” p. 166

8 Bryant, Julius. “Colonial Architecture in Lahore” p. 62

9 Shorto, Sylvia. “A Tomb of One’s Own” p. 167

10 Chopra, Preeti. “Anglo-Indian Architecture” p. 32

11 Ibid. p. 33

12 Shorto, Sylvia. “A Tomb of One’s Own” p. 160

13 Bence-Jones, Mark. “Government House Lahore.” p. 165

14 Ibid. p. 164

15 Shorto, Sylvia. “A Tomb of One’s Own” p. 164

16 Ibid. p. 162

17 Chatan, Robbin. “The Governors Vale Levu” p. 269

18 Srinivas, Tulasi. “Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City.” p. 1107

Bibliography

Bryant, Julius. “Colonial Architecture in Lahore: J. L. Kipling and the ‘Indo-saracenic’ Styles.” South Asian Studies 36, no. 1 (2020): 61-71.

Bence-Jones, Mark. “Government House Lahore.” PALACES OF THE RAJ: Magnificence and Misery of the Lord Sahibs. Routledge, 2018.

Chatan, Robbin. “The Governors Vale Levu: Architecture and Hybridity at Nasova House, Levuka, Fiji Islands.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 7, no. 4 (2003): 267-92.

Chopra, Preeti. “Anglo-Indian Architecture and the Meaning of Its Styles” Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay. 2011

Shorto, Sylvia. “A Tomb of One’s Own: The Governor’s House, Lahore.” Colonial Modernities: Building, Dwelling and Architecture in British India and Ceylon. Edited ByPeter Scriver, Vikramaditya Prakash. Routledge, 2007.

Srinivas, Tulasi. “Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City.” By William J. Glover. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. The Journal of Asian Studies 67, no. 03 (2008).

Image references:

Figures 1-3, Shorto, Sylvia. “A Tomb of One’s Own: The Governor’s House, Lahore.” Colonial Modernities: Building, Dwelling and Architecture in British India and Ceylon. Edited ByPeter Scriver, Vikramaditya Prakash. Routledge, 2007.

Figure 4, Bence-Jones, Mark. “Government House Lahore.” PALACES OF THE RAJ: Magnificence and Misery of the Lord Sahibs. Routledge, 2018.