Hashima Island is also widely known as Gunkanjima (Battleship Island) — its silhouette defined by concrete high rises, mining facilities and seawall resembling a battleship. This abandoned six-hectare island was once a glorious site of the undersea coal mines that fuelled rapid industrialization of Japan in the late 19th century to the 20th century. In 2015, Hashima Island was listed as UNESCO World Heritage Site, as a part of Nagasaki Prefecture in “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining” encompassing 23 sites of industrial facilities and institutions that accelerated Japanese modernization1. However, it is an exemplary site of a “difficult heritage”2 that overlooks reparations for Japan’s colonial ramifications that continue to this date. This case of Hashima Island as “difficult heritage” will be examined in different perspectives to discern multiple factors hindering its reconciliation with the colonial past and affected countries.

- Hashimoto, Atsuko and David J. Telfer. “Transformation of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island): From a Coalmine Island to a Modern Industrial Heritage Tourism Site in Japan.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 12, no. 2 (2017): 114-115

- Lee, Hyunkyung. “The Concept and the Roles of “Difficult Heritage”.” Korean Journal of Urban History 20, (2018): 169-172 “Difficult heritage” is a term referring to a site embedded with the painstaking and shameful history that forms and influences the site’s national identity upon becoming a site of heritage which is followed by both political and memory conflicts from its heritage-making process.

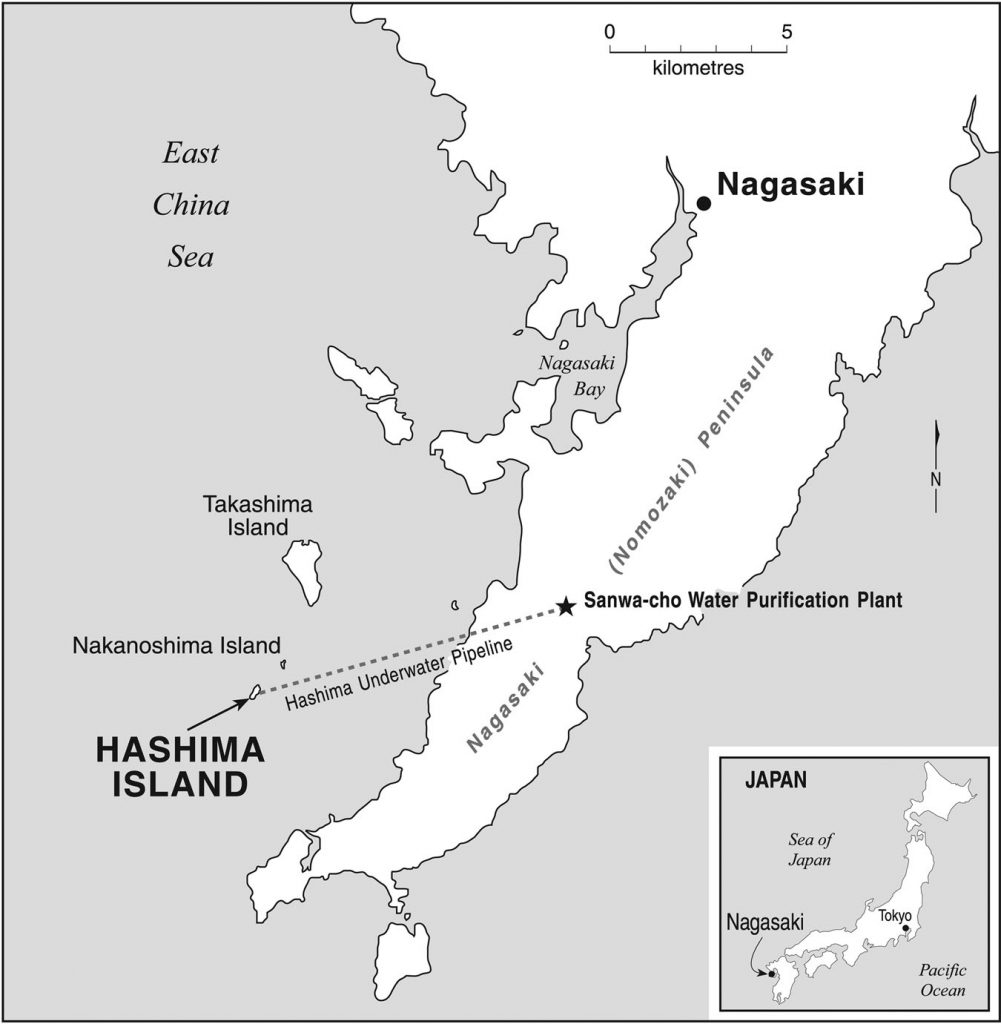

Hashima is located approximately 20km southwest of Nagasaki, a city that had an existing influx of Western knowledge and culture before the Japanese government opening their ports to foreign trade in 18543. Thus, the island’s proximity to Nagasaki allowed Western technologies to be easily introduced to its coal mining practice4. In the mid-19th century Northern Kyushu, coal was already in use for personal consumption and coal digging on Hashima began in 1810 at a modest scale for fishermen as a source of extra income5. With the dawn of the Meiji government, Japan became more reliant on coal as a vital resource to sea salt production, iron manufacturing and steam engine operations5. In 1872, all coal mines in Japan were claimed by the Meiji government and in 1890 the Mitsubishi Conglomerate purchased Hashima Island along with two neighbouring islands for more extensive undersea coal extraction5. By 1941, Hashima island alone produced 410,000 tons of coal5. Active adoption of Western technologies was not only successful in their defences against the colonial West but also established solid foundations for generating national economic wealth. In the mid 20th century, crude oil from the Middle East and imported coals became more available and by 1964 more than 99 per cent of domestic use was dependent on imported coal in Japan4. With decreasing production of coal and the resource depletion on Hashima Island, Mitsubishi closed its mining facility in 19746.

3. Hong, Insoo. “The “social life” of industrial ruins : a case study of Hashima Island.” Thesis, University of Cape Town, Faculty of Humanities, African Studies, 2015: 15

4. Hong, 21

5. Hashimoto et al., 110

Northern Kyushu is a region encompassing Fukuoka, Saga, Nagasaki, Kumamoto and Ōita prefectures

6. Hashimoto et al., 111

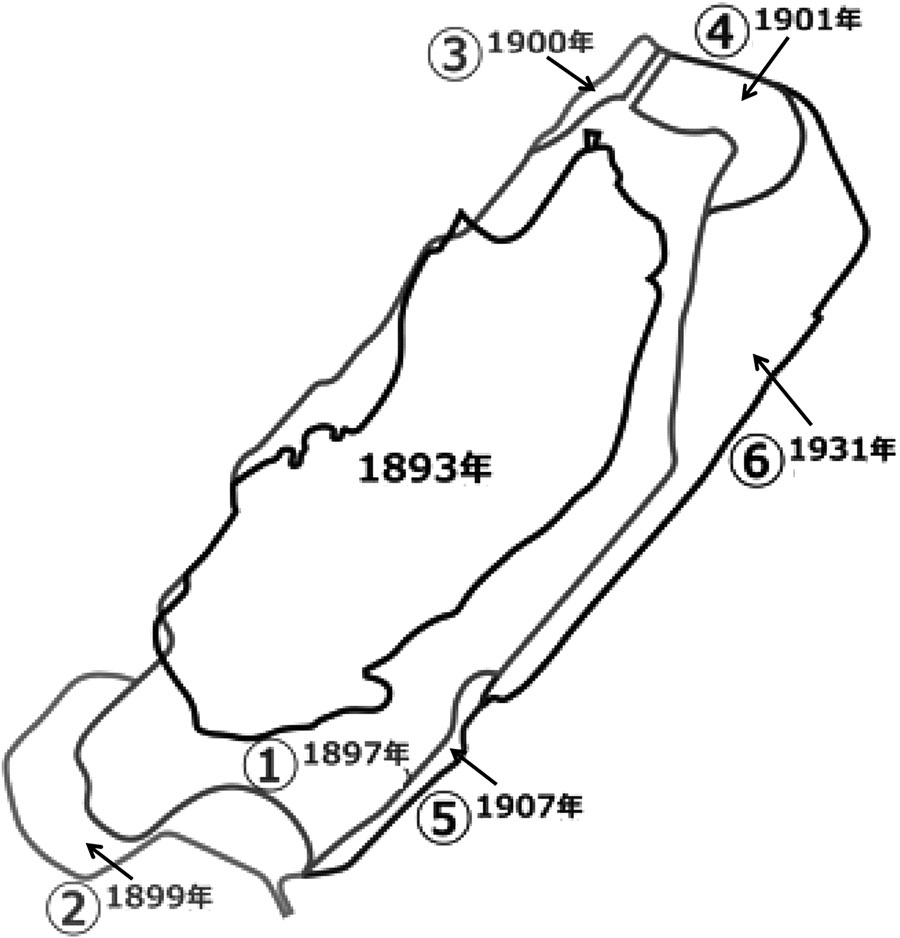

Before Mitsubishi acquired Hashima, it was a small reef island that was roughly 0.02km2 in size7. Over the course of 30 years, the island expanded to its current size of 0.06km2 7. To accommodate the growing population from the influx of labourers and their families, the first concrete high-rise apartment in Japan was built on Hashima Island. Its population peaked in 1960—up to 5300 people had lived on this small island which is less than half the size of Granville Island in Vancouver, Canada — recorded as one of the highest population densities of the world7. Hashima was equipped with all the necessary amenities to fulfill the needs of the islanders such as school, playground, hospital, sports complex, post office, public baths, shrine, cinema, bars, billiard, casinos, parlours, brothel, groceries and hardware shop7. In total, there were thirty concrete buildings compactly erected on this tiny piece of land where “one could walk between any two points on the island in less than it took to finish a cigarette”, creating “a labyrinth of corridors and staircases connect(ing) all the apartment blocks” as described by Burke-Gaffney8. Absent of human life or natural resources, Hashima is now “a concrete mass of constellations and significations”, which Burke-Gaffney portrays as “the end result of ‘development’… what the world would be like when we finish urbanizing and exploiting it: a ghost planet spinning through space – silent, naked, and useless”8.

7. Hashimoto et al., 112-3

The island went through six phases of expansion in 1897, 1899, 1900, 1901, 1907 and 1931.

8. Lavery, Carl, Deborah P. Dixon, and Lee Hassall. “The Future of Ruins: The Baroque Melancholy of Hashima.” Environment and Planning. A 46, no. 11 (2014): 2571-2

The architectural ruins of “a microcosm of Japan’s early industrial capitalism”9 is embedded with traces of lives that populated the island — invoking the nostalgic poetics of space and also remains as a glorified national monument to industrialized Japan. In its uncanny, eerie and elemental state, the island has been an attractive source of ruination images that fall into the Japanese postindustrial genre and also an “Anglo-American visual economy of “ruin porn” composed of abandoned buildings haunted by the remains of past lives”10. Such romanticized framework of Hashima Island becomes a medium that obscures the memories of labourers who were forcefully conscripted and exploited by imperial Japan — embedded 1000m below grade in the narrow under sea coal mines. Hashima Island’s appearance in a James Bond movie Skyfall (2012) is a great example that reveals this amnesic heritage making process. The island featured in the movie captivated international attention, which eventually led Google to produce an interactive Street View navigational interface that linked to the film’s narrative11. Synenko argues that this “prolific visual culture … encouraged Japan to adopt a triumphalist attitude toward the sites of its industrial past and reinforced with films like Skyfall … replacing expressions of loss, trauma or reparation with hollow themes intended to produce mass entertainment”12. Synenko also believes that the film and aforementioned Google Street View project served as a “motivator to preserve the site’s physical remains … (which) not only bolstered (the island’s) tourism campaign, but also bestowed legitimacy on Japan’s bid to include the surrounding region under UNESCO’s list of protected sites … without any formal recognition of the injustices that resulted from Japan’s policy of conscripting miners from China and Korean Peninsula”11, 12.

9. Synenko, Joshua. “Geolocating Popular Memory: Recorded Images of Hashima Island After Skyfall.” Popular Communication 16, no. 2 (2018): 145

10. Dixon, Deborah P., Mark Pendleton, and Carina Fearnley. “Engaging Hashima: Memory Work, Site-Based Affects, and the Possibilities of Interruption.” Geohumanities 2, no. 1 (2016): 167

11. Synenko, 141

12. Synenko, 142

The making of heritage by domineering culture reinforced through the narratives of prosperous industrial achievement of Japan and fetishization of the architectural ruins occlude the history of “aggression, exploitation, militarism, (corporate) fascism and discrimination” experienced by the Korean and Chinese labourers in the Hashima mines13. In the 1890s — prior to the Japanese colonial occupation of Korea — it was mostly convicts who were sentenced to terms of hard labour that inhabited and worked on Hashima Island 14. Japanese colonization of Korea began in 1910, which deprived Korean peasants of their lands and they were eventually conscripted as labourers to the various mining facilities in Japan15. To fulfill the shortage of stable Japanese workforce during World War II and the Pacific War, “colonial surplus population” became the vital workforce in the high demand mining industry15. In 1938, colonial Japan “enacted martial law concerning the mobilization of human resources and material” that legitimized extensive and coercive conscription of Korean labourers to “help produce munitions and fuel” during the war period16. By 1944, Hashima and Takashima Island “housed … 1,355 Korean workers … about 25 per cent of the population” working under the extreme conditions “1000m below sea level, where methane gas accumulated in the cramped shafts”17. As a result, 122 of “(unpaid), malnourished, and overworked”17 Koreans died suffering from diseases, injuries and accidents16. This time period coincides with when Hashima reached its peak of coal production in the 1940s. Yet, only a few historical records and the voices of the survivors acknowledge or testify the painstaking history of Hashima Island.

13. Hong, 25

14. Hong, 24

15. Hashimoto et al., 121-122

16. Hong, 22-23

17. Dixon et al.,173

Young-Sik Jeon, one of the few survivors from this island recalls of their living conditions on the island recalls his memory of discriminatory and poor living conditions of the island in his interview featured in a documentary Hell Island: Gunkanjima produced by KBS (Korea Broadcasting System) in 2010: “In the 9-floor building, the lowest level basement suites were for Koreans. There was no sunlight, not much ventilation”18. Being at the lowest and closer to the seawall, it was prone to flooding when waves were high. The windows were gated by metal fences to prevent them from escaping with a watchtower nearby18. On the contrary to being represented as a celebrated achievement of modern Japan, the foreign labourer’s experience of the first concrete high-rise apartment in Japan was close to living in a prison cell. Those who died without relatives were cremated and buried on Hashima island. However, when the Mitsubishi corporation evacuated Hashima Island in 1974, their urns were relocated to a cemetery for foreign workers on the neighbouring Takashima island19. During this process, the company burned all the records such as nameplates that contained information about their place of origins and causes of death19. According to Dakajane, a local representative of Nagasaki Zainichi Kankoujin no jinken o mamoru kai(Nagasaki Association to Protect the Human Rights of Korean Residents) group, notes that when the Mitsubishi left Takashima mines in 1988, they destroyed the cemetery entrance and the surrounding stonewalls20. The corporate’s effort to disregard and conceal the history of atrocity continues today: “The extent of Mitsubishi’s exploitation of … workers is still clouded by the corporation’s long-running efforts to deny compensation and to restrict access to historical records”17. In 2017, the city of Nagasaki permanently closed the way to the cemetery, claiming that the urns have been moved to a nearby temple without providing clear reasons or confirmation of their relocation21. Even after their deaths, perished victims of exploited labour are still at unrest from politics involved in the fine-tuning of heritage narrative.

18. KBS (Korea Broadcasting System), History Special, episode 41, “Hell Island: Gunkanjima”. aired August 8th, 2010. “https://youtu.be/7QSDGLvfi4k”:16:32-16:50

19. KBS (Korea Broadcasting System), 45:17-45:36

20. KBS (Korea Broadcasting System), 44:30-44:40

21. Wang, Kil Hwan. “Japan, Permanently Blocking the Entrance to ‘Offering Memorial’ Where Korean Forced Labourers Are Buried”. Yeon-Hap News, March 23, 2017. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20170322176500371

As a nonprofit campaign group leader of Gunkanjima o Sekai isan ni suru kai (The Association to Make Gunkanjima a World Heritage Site), Sakamoto Doutoku shares his fond nostalgia of Hashima in the 1960s and 1970s by leading commercial and other tours to the island and through written publications of the island22. He has been “the primary facilitator of interaction with the island for former residents, academic researchers, and documentary and feature filmmakers”, again reproducing and reinforcing the romanticized narrative of Hashima island with no regards to its brutal history22. Thus, his spatial memory of the island has “ossified into a particular path … which a specific narrative of the past is constructed … that weaves its way through the mass of Hashima-related publishing and heritage campaign materials” 23. This particular path of narrative along with decontextualized ruin fetishization foster Japan’s unwillingness to confront and acknowledge the “difficult heritage” and prolong the colonial ramifications of their imperial past. Without proper reconciliation from the island’s past of “historical injustice, labour maltreatment, imperialism, and global industrial capitalism”24, it remains in situ as a site of violence and exploitation yet generating wealth by attracting ruin enthusiast and alike — continuously cultivating and reproducing colonial views.

22. Dixon et al.,168

23. Dixon et al.,184

24. Synenko, 151

Bibliography

Dixon, Deborah P., Mark Pendleton, and Carina Fearnley. “Engaging Hashima: Memory Work, Site-Based Affects, and the Possibilities of Interruption.” Geohumanities 2, no. 1 (2016): 167-187.

Hashimoto, Atsuko and David J. Telfer. “Transformation of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island): From a Coalmine Island to a Modern Industrial Heritage Tourism Site in Japan.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 12, no. 2 (2017): 107-124.

Hong, Insoo. “The “social life” of industrial ruins : a case study of Hashima Island.” Thesis, University of Cape Town, Faculty of Humanities, African Studies, 2015

KBS (Korea Broadcasting System), History Special, episode 41, “Hell Island: Gunkanjima”. aired August 8th, 2010. “https://youtu.be/7QSDGLvfi4k”

Lavery, Carl, Deborah P. Dixon, and Lee Hassall. “The Future of Ruins: The Baroque Melancholy of Hashima.” Environment and Planning. A 46, no. 11 (2014): 2569-2584.

Lee, Hyunkyung. “The Concept and the Roles of “Difficult Heritage”.” Korean Journal of Urban History 20, (2018): 163-192.

Synenko, Joshua. “Geolocating Popular Memory: Recorded Images of Hashima Island After Skyfall.” Popular Communication 16, no. 2 (2018): 141-153.

Wang, Kil Hwan. “Japan, Permanently Blocking the Entrance to ‘Offering Memorial’ Where Korean Forced Labourers Are Buried”. Yeon-Hap News, March 23, 2017. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20170322176500371

Images

- Title: Lee, Yong-Hwan. The Island Scenery, Gunkanjima. copyright 2013. http://www.mu-um.com/?mid=02&act=dtl&idx=17019 (April 26 2021)\

- Figure 1. and 2.

- Hashimoto, Atsuko and David J. Telfer. “Transformation of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island): From a Coalmine Island to a Modern Industrial Heritage Tourism Site in Japan.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 12, no. 2 (2017): 107-124.

- Figure 3.

- https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/hashima-skyfall-island-visit/index.html

- Figure 4

- Yoshitaka, Akui. Gunkanjima no kindai kenchikugun ni kansuru jisshôteki kenkyû [Site Research on the Modern Architectural Forms of Gunkanjima], Tokyo: Tokyo Denki Daigaku

- Figure 5.

- Still from KBS (Korea Broadcasting System), History Special, episode 41, “Hell Island: Gunkanjima”. aired August 8th, 2010. “https://youtu.be/7QSDGLvfi4k”: 16:07

- Figure 6.

- Google Earth