The life after death for a colonial British cemetery in India

In the early nineteenth century, England was undergoing a period of rapid development due to industrialization. This led to an urban population boom in places like London especially, which ushered in changes to much of the city’s infrastructure in order to accommodate the new influx of bodies. A large but easily overlooked system that was undergoing a major reform at this time was the cemetery.1 The existing tradition, which consisted of burial in small churchyard cemeteries on church properties was becoming no longer feasible, with the number of bodies needing to be accommodated far outweighing the given space. At this point, the process of cremation was unpopular, so the obscable became simply finding much more space for buried bodies and designing these spaces appropriately. Another contributor to the need for more cemetery space revolved around the growing idea of needing to improve sanitation.2 It was believed at the time that contamination of the air led to disease (which was a theory called miasma) with the improper handling of dead bodies and overcrowding of cemeteries believed to spread disease. This funerary landscape was beginning to evolve in the 1830’s, with places such as Kensal Green opening in London in 1833,3 and in British colonies such as the Mount Auburn cemetery in Massachusetts, U.S.A in 1831.4

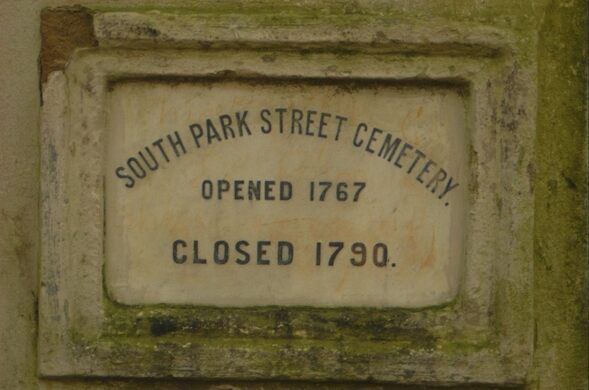

An area under British colonization at this time was India, which saw their own development of British graveyards made to house the colonizers that had died within India. Although the British made up an extremely small proportion of the Indian population, their power as colonizers allowed them to create separate burial spaces, exclusive from the majority Indian population. One of these colonial-era British cemeteries in India is the South Park Street cemetery in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta). This cemetery was established in 1767, preceding even early British examples by over fifty years. It is also one of the earliest examples of a cemetery that is not connected to a church and was likely the largest Christian cemetery outside of Europe and North America in the nineteenth century.5 South Park Street cemetery was created by the British in Kolkata to bury exclusively British colonizers and did not mix or allow any Indian people to be included. Graveyards such as South Park Street are significant because they act as the final resting place for many British colonizers while situated on colonized land and for that reason cannot be conflated with other early Victorian cemeteries in England. These British graveyards were established across the subcontinent during colonization, with South Park Street being one of the oldest and largest.6 Many of these cemeteries still exist today in varying states, with some of them having been left to nature since the British had left India, with monsoons, vegetation and the overall elements taking the land back. Others, such as South Park Street have seen intermittent maintinance over the years. This neglected treatment of these spaces reveal clues about the general sentiment that Indian population feels about these colonial-era British cemeteries. These areas were taken from the people of India, and the colonizers that did this taking were buried under their taken land at places such as South Park Street. This historical remnant of colonization in India is able to reveal ideas about the British-Indian relations at the time of colonization and provoke ideas surrounding how these cemeteries should be treated by post-colonial India.

South Park Street cemetery was established in the late eighteenth century within what was a dense bamboo forest outside of the more populous city of Kolkata (whose population was already over one million people). The area was used frequently by the colonial elite for tiger hunts. After the first burial at South Park Street, the cemetery grew to over 1600 tombs,7 many of which were monumental in scale and decorated with any number of Egyptian, Green and Indo-Sarecenic forms. Some of this variety can be seen in Figure 1, with the cemetery containing a combination of obelisks, pyramids, Greek columns adorning the British tombs. Features of Hindu architecture and features from Islamic tombs have also been borrowed in certain instances8, reflecting not only a cultural mixing but also an appropriation of religious motifs. Those buried at South Park Street came from a variety of different backgrounds and professions, from the colonial bureaucracy and military, to more common citizens, including: secretaries, a schoolteacher, a silversmith, housewives and children. The mortality rate of British living in India at the time was very high, with life expectancy under thirty for men and under twenty five for women,9 caused largely by diseases such as malaria. The opulence of the tombs that these people were laid to rest in South Park Street reflected the status of the individual to a certain extent, but also reflected the self-image of the strength and grandeur of the British within a colonized land, codifying their power into the landscape around them. It was important for the British colonizers to display their elevated status over the Indians, even in death, through architectural displays like those found at South Park Street.10

As the British Raj came to an end in the mid-twentieth century, South Park Street cemetery has now been a non-active cemetery for roughly 150 years, and the newly independent nation is beginning to try and determine whether this British colonial cemetery carries historical significance, and is worth preservation and conservation. Many other European cemeteries in India have fallen into disrepair with the departure of the colonizing force that established them, and left to the devices of nature these spaces of death are experiencing a second death. First there was “the decaying remains of its inmates, and its own death, as it lies forgotten by both the past and present”.11 During the British Raj, there had been another section of the cemetery, North Park Street cemetery, which was demolished in 1957 by the Indian government to make way for future apartment complexes.12 The South Park Street cemetery was left as is and intended to be maintained, although the cultural heritage of the space was something that carried very little meaning to the post-colonial Indian citizen. This colonial space, which was made by and intended for the British colonizers, felt irrelevant to most Indians. This becomes especially poignant when you consider that the religious majority of Hindu practice cremation over burial. Muslim’s do pactice burial, but overall this cultural environment shared very little with the European Christian burial traditions.13 This left the cemetery between time and space, between the colonial and post-colonial, and between England and India while residing in neither.

From the 1970’s to the present day there has been a renewed interest in the South Park Street cemetery and its counterparts. This interest is from the organization BASCA (British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia), based out of England who see value in the preservation and restoration of these cultural heritage spaces.14 From the side of the ex-colonizer, who in today’s day have long ceased any claims to the land in India that cemeteries such as South Park Street rest upon, have an increased interest in the heritage from the time of the British Raj. BASCA’s efforts have not been able to preserve all colonial British cemeteries, since cooperation has to be achieved with local South Asian governments and organizations which now own the land and are responsible for the maintenance and upkeep. South Park Street has continued to this day largely from sustained efforts by BASCA and the Indian conservationists that believe the colonial history at the cemetery is worth preserving, even the city of Kolkata has ballooned to over thirteen million people, and the area surrounding the cemetery is now a bustling shopping district of high rises.

These can also be seen in the historical image shown in Figure 1.

Figure 6 (right). Image of the tomb of Major-General Charles ‘Hindoo’ Stuart, constructed with a much more Indo-Sarecenic design. https://www.livehistoryindia.com/story/history-daily/south-park-street-cemetery-the-dead-still-tell-tales/

Together, these tombs provide a glimpse into the variety of designs that were being constructed at South Park Street.

The preservation of South Park Street will continue to be one of ambivalence and of conflicting opinions. The neglect and state of disrepair many of these colonial graveyards are experiencing today are not unlike the ways that the British treated the old cities of India they initially encountered,15 which were demolished to pave way for the European modes of urban planning. Now that the same is happening to the spaces where these very colonizers reside, organizations such as BASCA now see issues in the loss of their own cultural heritage. These sentiments towards preservation of such monuments and spaces have been seen as displays of “nostalgia and melancholy tour(s) to former colonies . . . enabled the traveller to relive the glory days of the empire while simultaneously mourning their demise”.16

However the physical space of South Park Street cemetery is handled in the future, its current history is a testament to the constantly evolving meanings that can be carried through architecture and landscape architecture. The built environment is subject to constant change, with South Park Street’s long history undergoing a continual physical transformation while the beliefs of the individuals involved with this cemetery change as well. As India continues to navigate and take inventory of the remnants from British colonization, South Park Street cemetery will be wedged within the city as a physical memory of a colonial past, forgotten and fading away to some and a valued space of cultural heritage to others.

Notes

1 Elizabeth Buettner, “Cemeteries, Public Memory and Raj Nostalgia in Postcolonial Britain and India.” History and Memory 18, no. 1 (Indiana University Press, 2006), 10.

2 Agatha Herman, “Death has a touch of class: Society and space in Brockwood Cemetery, 1853-1903.” Journal of Historical Geography (Cardiff University, 2010), 5.

3 Herman, “Death has a touch of class,” 5.

4 Aaron Sachs, “American Arcadia: Mount Auburn Cemetery and the Nineteenth-Century Landscape Tradition.” Environmental History 15, no. 2 (2010): 206.

5 Ashish Chadha, “Ambivalent Heritage: Between Affect and Ideology in a Colonial Cemetery.” Journal of Material Culture 11, no. 3 (2006): 341.

6 Chadha, “Ambivalent Heritage,”341.

7 Chadha, 345.

8 Buettner, “Cemeteries, Public Memory and Raj Nostalgia in Postcolonial Britain and India,” 12.

9 Chadha, 359.

10 Chadha, 344.

11 Chadha, 340.

12 Chadha, 345.

13 Buettner, 24.

14 Buettner, 7.

15 Buettner, 22.

16 Buettner, 14.

Bibliography

Buettner, Elizabeth. “Cemeteries, Public Memory and Raj Nostalgia in Postcolonial Britain and India.” History and Memory 18, no. 1 (Indiana University Press, 2006): 5-42. Accessed April 23, 2021. doi:10.2979/his.2006.18.1.5.

Chadha, Ashish. “Ambivalent Heritage: Between Affect and Ideology in a Colonial Cemetery.” Journal of Material Culture 11, no. 3 (2006): 339-363.

Herman, Agatha. “Death has a touch of class: Society and space in Brockwood Cemetery, 1853-1903.” Journal of Historical Geography (2010): 1-21

Sachs, Aaron. “American Arcadia: Mount Auburn Cemetery and the Nineteenth-Century Landscape Tradition.” Environmental History 15, no. 2 (2010): 206-235.

Schuyler, David Paul. “Public Landscapes and American Urban Culture 1800-1870: Rural Cemeteries, City Parks, and Suburbs.”ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1979.

“Built Spaces: Conservation of South Park Street Cemetery,” YouTube video, 11:55, “Sahapedia,”May 9, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2M1dEutk0yE.