The Japanese Imperial Mint is a British-colonial style brick factory that was the first of its kind in Japan, designed by Irish architect, Thomas Waters. Though the mint’s sole purpose was to produce coins, there were colonial undertones in its history. Even before its opening in 1871, much of its activities often fell under the authority and jurisdiction of the British despite the building being on the grounds of Japan. Through exploration of its style and external influences, this text will begin to understand how the mint became the stepping stone to advancing modern-day japan. Likewise, it will examine the implications of western principles during the Meiji Era and how the transformations in architecture through a colonial power began to shift the dynamics of the society in Japan.

Though Japan takes on one of the world-leads on technological advancements in the 21st century, its success is attributed to its willingness for western expansion in the mid-1800s. However, Japan was initially hesitant; its livelihoods thrived on local, agricultural means and a majority of the lifestyles surrounded that of the traditional. As time passed, the throne realized that they had no choice but to keep pace with the advancement seen in the west. Thus, the prospects to advance as a country took form during the 1850s-1860s in the Meiji era, when the country opened its doors to the west, marking the pinnacle time of western domination in Eastern Asia. In the beginning, the journey to modernization was envisioned as a feat accomplished by Japan themselves, who imagined becoming an icon of modernization and thriving in foreign trades as an essential player in global trades. However, after realizing that they had lacked the resources, they reluctantly accepted help from the western foremen.[1] Likewise, this realization also prompted them to sign treaties with western countries to become an essential part of the global trade.[2] Pressured and held under the reigns of western influences, Japan agreed to help build the mint to ease the nerves of Britain, who felt restless due to the widespread use of the Mexican dollar as the main currency in trade. As a result, following in the footsteps of the discontinued mint in Hong Kong, the Japanese Imperial Mint was born with the purpose to produce a stable supply of coins and secure their positions within the foreign trade.[3] Not surprisingly, this collaboration began to curate as a mutualistic relationship only in its early stages: the British were able to fulfill their visions of eastern expansion while the Japanese were able to make their footprint in foreign trade. However, a power struggle began between the two parties, and despite Japan’s expectation of taking control, the British exerted control through numbers of workers and the Japanese Imperial Mint ultimately fell under the control of a British Finance company.[4] As such, without regard to the Japanese workers, much of the processes were supervised by foreigners who wanted to ensure that work was done as it was in Britain.[5]

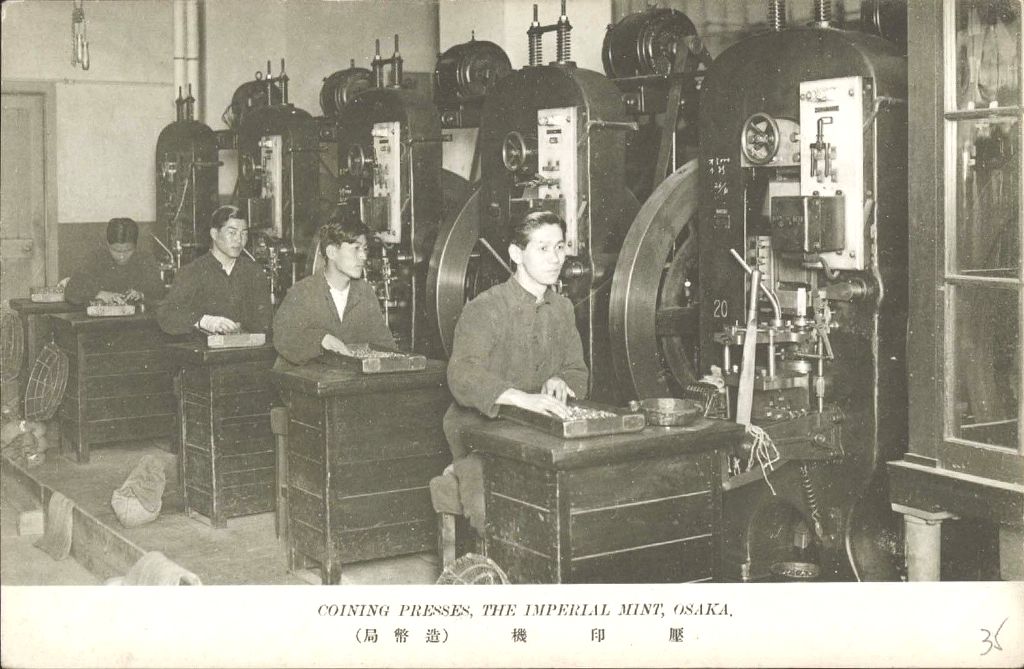

The Japanese Imperial Mint consists of several buildings, ranging from the coining factory where mainly coins were produced, a Senpukan which was a guest house built for honorary guests most often inhabited by the emperor and his family, and two other homes for workers on site. The buildings are decorated by tall, structural steel columns that were imported from England and wide verandas that wrapped around the facade. The neoclassical veranda style was heavily driven by the voices of the British merchants that brought upon their men, plans, and machines that resulted in the colonial aesthetic.[6] When looking at the floorplans, the drawings are laid out in a very symmetrical and organized manner suggesting traces of British influences and the bias toward western aesthetics. Apart from using local materials, there are no traces of other Japanese-influenced designs in the mint. Similarly, the architects ensured that its preference for efficiency informed the program of space. The factory was designed in a fashion where entrances were limited and that there was no free-roaming throughout the entire floor to limit laborers from leaving their posts during the workday.[7] It was common for a place of such importance to be designed under considerations of high security; however, it did not justify the lack of washrooms available to the workers. Such design decisions begin to suggest the implementation of colonial dominance through buildings whereby the colonial designer is granted full power to control the social dynamics of space.

The Japanese Imperial Mint was one of many western-style buildings constructed during the Meiji Era. This meant that apart from the specific needs of the factory program, its general identity was very similar to other buildings of its time. As it was built in the early Meiji Era, excluding some decorative aspects of building facades, the building organization favoured practicality and functionality. In these cases, views were not prioritized and all buildings were built to fulfill daily usage.[8] Though, it is important to note that this is most often the case for buildings designed by western architects. In cases where local carpenters had a voice, the buildings took on a more decorative approach, often using symbolic characters such as dragons or phoenixes, to adorn buildings.[9] Interestingly, the stylistic choices and floor plans were drawn from the mint in Hong Kong, which began to garner criticism due to its lack of “local circumstances” that were being neglected in drawings and design. In many examples, only general information was recorded in the western documents.[10] These observations begin to suggest the amount of power in controlling how information is perceived and begin to allude to authority held by the colonizer.

Despite the conflicting history of power, the present-day Japanese Imperial Mint is still a spectacle to many. The remnants of the factory and guesthouse are being carefully refurbished and displayed, as a token of understanding the history of modernization in Japan. As part of the origin of modernization, the mint symbolizes the important decision of welcoming modernization. Though in the beginning, the interest of Japan was not considered by the western colonizers. However, their intent to promptly introduce new technologies along with the mint, such as telegraphic service and railways, made its way into Japan and brought Japan closer to reaching its vision due to their eagerness to absorb this transfer of technology.[11] Subsequently, the country progressed from the Meiji Era, when new dynamics began and modern lifestyles took over. From bullet trains, suits, and trendy haircuts, to modernized military and western education, Japan took on a new identity in renewal to its traditional past.[12]

Through the exploration of the Japanese Imperial Mint, the structure becomes a lens into the implications of colonization. Despite intentions of collaborative efforts, the power stands with that of the colonizer, often with minimal struggle. In this case study, the British held the authority to dictate space: how the buildings are used, who used them, or when they could be used. It begins an interesting conversation in understanding the power structures of space and how they can start to inform more productive practices moving forward. Nonetheless, the Japanese Imperial Mint is one of many examples of how colonial forces begin to transform the anatomy of society and is one of the critical components in understanding the modernization of Japan.

Footnotes:

[1] Susumu Mizuta, Making a Mint: British Mercantile Influence and the Building of the Japanese Imperial Mint, 92.

[2] Kenichi Ohno, Meiji Japan, 87.

[3] Susumu Mizuta, Thomas Waters and the Paper Money Factory Project of Meiji Japan, 282.

[4] Susumu Mizuta, Making a Mint: British Mercantile Influence and the Building of the Japanese Imperial Mint, 96.

[5] Kenichi Ohno, Meiji Japan, 94.

[6] Susumu Mizuta, Making a Mint: British Mercantile Influence and the Building of the Japanese Imperial Mint, 91.

[7] Susumu Mizuta, Making a Mint: British Mercantile Influence and the Building of the Japanese Imperial Mint, 101.

[8] Somchart Chungsiriarak, Modern (Western Style) Buildings in the Meiji Period (1868-1912) With Comparison to Contemporary Western Style Buildings in Siam, 131.

[9] Somchart Chungsiriarak, Modern (Western Style) Buildings in the Meiji Period (1868-1912) With Comparison to Contemporary Western Style Buildings in Siam, 132.

[10] Susumu Mizuta, Making a Mint: British Mercantile Influence and the Building of the Japanese Imperial Mint, 102.

[11] Kenichi Ohno, Meiji Japan, 94.

[12] Roy Starrs, Constructing Meiji Modernity, 14-15.

—

Bibliography:

Chungsiriarak, Somchart. 1. “Modern (Western Style) Buildings in the Meiji Period (1868-1912) With Comparison to Contemporary Western Style Buildings in Siam”. NAJUA: Architecture, Design and Built Environment 16 (1), 123. https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/NAJUA-Arch/article/view/46020.

Mizuta, Susumu. “Making a Mint: British Mercantile Influence and the Building of the Japanese Imperial Mint.” Architectural History 62 (2019): 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1017/arh.2019.4.

Mizuta, Susumu. “Thomas Waters and the Paper Money Factory Project of Meiji Japan.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 17, no. 2 (2018): 277–84. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.17.277.

Ohno, Kenichi. “Meiji Japan.” How Nations Learn, 2019, 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198841760.003.0005.

Starrs, Roy. “Constructing Meiji Modernity.” Essay. In Modernism and Japanese Culture, 13–15. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

—

Images:

Japanese Imperial Mint Overview: https://www.meijishowa.com/photography/1361/70808-0006-imperial-mint

Coin pressing: http://www.worldofcoins.eu/forum/index.php?topic=11734.0

Coin inspection: http://www.worldofcoins.eu/forum/index.php?topic=11734.0

Entrance portico, Senpukan, & Floor plan: Mizuta Susumu – Making a Mint: British Mercantile Influence and the Building of the Japanese Imperial Mint