Rangoon (Yangon) has a complex history as Burma’s (Myanmar) largest city, its former capital, and most influential port city. The Port Trust Office (Myanma Port Authority building) was designed by Thomas Oliphant Foster and completed in 1928.[1] A powerful beacon in contemporary Yangon, the Port Trust Office represents British Imperial Power over its inhabitants, streetscapes, commerce, and state; a colonial invention of governance inherited and upheld by the former and now current Military Dictatorship. This entry looks at the Port Trust Office through its historical context, its relationship to colonial authority and trade commerce, and its legacy as a symbol for British Imperial Power on the waterfront.

[1] Pedro Guedos, “Behind the Veils of Modern Tropical Architecture,” Docomomo International (blog), January 21, 2021, https://www.docomomo.com/articles/behind-the-veils-of-modern-tropical-architecture.

Anglo-Burmese Wars

Burma has a long history of discourse between various ethnic groups dating back to the first century including the Mon, Pyu, Shan, and Burmese peoples. The last Burmese dynasty, Konbaung, came to power after the occupation of the Toungoo dynasty in the 1750s, and seized lands over the next century that would make modern day Myanmar. Land seizures to the northwest, including Arakan, resulted in Arakanese fleeing from Burmese rule into British occupied India.[1] Continued border disputes in the north culminated in the first Anglo-Burmese war of 1824-1826 where the British stormed Yangon, raided pagodas, and defeated the Burmese. A treaty was signed without question forcing the Konbaung dynasty to pay a million pound indemnity and relinquish their coastal territories of Arakan (Rakhine) and Tenasserim (Mon & Tamintharyi).[2] The acquisition of land was the colonist’s first attempt of domination over Burma and the indemnity would consequently be the fall of the dynasty.

In 1852, the British would instigate the second Anglo-Burmese war over superficial disputes between the Yangon governor and East India Company. This resulted in colonial acquisition of the lower province Pegu (Yangon) including the City of Rangoon (Yangon) which became Britain’s commercial and administrative hub in Burma.[3] The third and final Anglo-Burmese war took place in 1885-1886 which abolished the Konbaung dynasty entirely and allowed for the annexation of the rest of the Kingdom into a province of British India.[4] British occupation remained a strong hold until the Japanese air strikes of 1941;[5] and though this marked the end of British Burma, the colonial buildings, systems, and authoritarian leadership remains today.

[1] John Middleton, World Monarchies and Dynasties (Routledge, 2015): 132-134

[2] Donald Seekins, (2011). “The rise and fall of British Rangoon, 1824-1941” State and Society in Modern Rangoon (1st ed.). Routledge (2011): 28-29

[3] Seekins, “The rise and fall of British Rangoon, 1824-1941,” 29

[4] Middleton, World Monarchies and Dynasties, 134

[5] Jasnea Sarma and James D. Sidaway, “Securing Urban Frontiers: A View from Yangon, Myanmar,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44, no. 3 (2020): 445

Colonial Port City

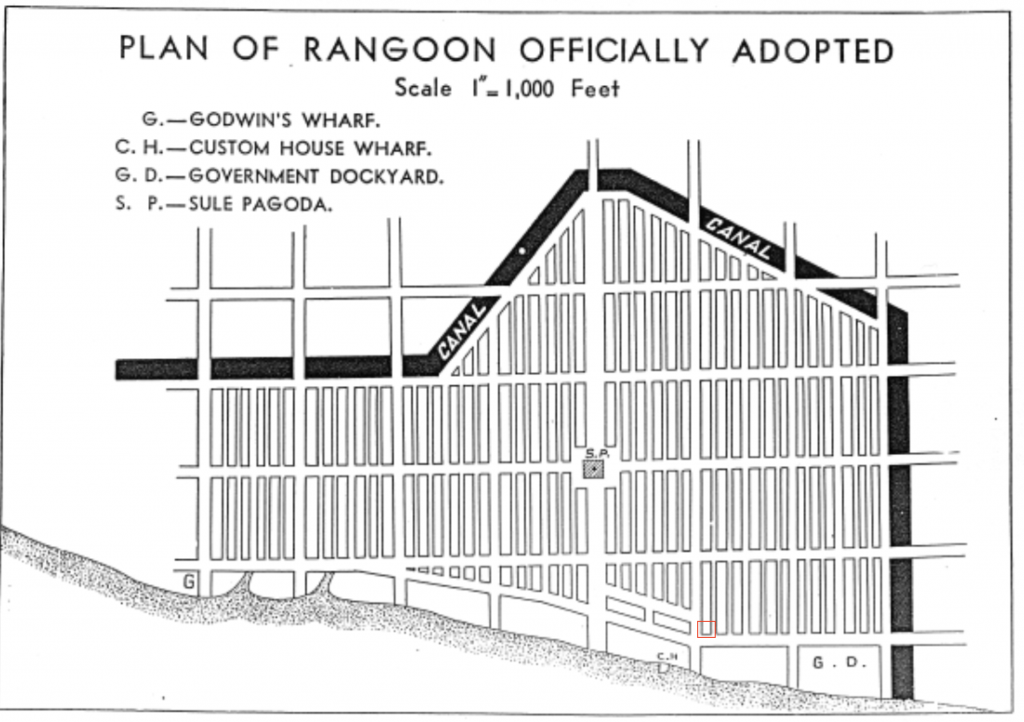

After the acquisition of Lower Burma in 1852, immediate efforts were taken to redevelop Rangoon. The proposed city plan was two square kilometres of “space which was demonstrative of British superiority and importance,”[1] including a rectilinear grid with a downtown business district and wide streets for sanitation (and population control). The planning of Rangoon “was explicitly designed as a capital city to serve the needs of the colonial state: to encourage trade and instigate order in a newly conquered territory”[2] and “rendered the city more readily ruled, more legible within British conceptions of order and manageability.”[3] The design for the new city layout took precedent from British colonial Malaysia and Singapore and has been referred to as a form of Haussmanization of the extant architecture.[4] The establishment of Rangoon as a colonial port city marked the imperial domination by British through land dispossession and consolidation of commerce from the Konbaung dynasty.

Burma’s shared borders with India and China, two powerful and diverse economies, offered a unique opportunity for the region as a global trading centre.[5] Early control of Burma was narrowly militaristic, however colonial policy was synonymous with British economics, and focus was placed “on export of commodities and raw materials and import of manufactured goods.”[6]

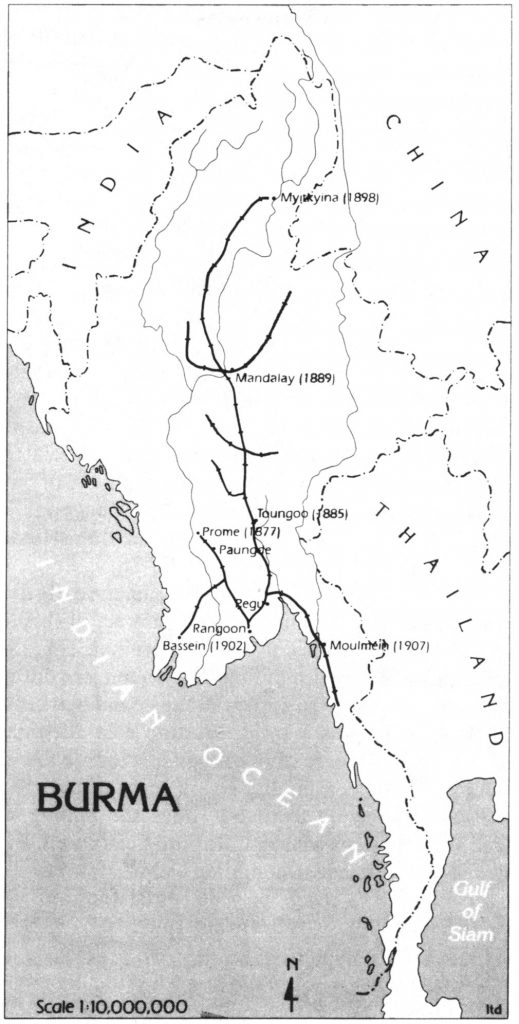

Rice was one of Burma’s largest exports and British interest in the area steadily grew with rising global market prices. Growing demand for rice in tandem with the opening of Suez Canal in 1869 motived the colonists to invest in infrastructure and public works projects for roads, canals, and railways. After the third Anglo-Burmese war and annexation of the rest of Burma under British rule, railways were extensively developed. [7] This emerging transportation system collected rice paddies from inland Burma to be exported at Rangoon’s port. This led to a stimulus in rice exports and helped make Rangoon the richest colonial port city.[8] Efforts to connect Upper and Lower Burma as well as intensify the production of rice (and teak wood and petroleum) exports were a colonial consolidation of commodity and natural resources that only benefited European and other foreign investors. This colonial economic model and transportation system coalesced at Rangoon’s port where commodity was evaluated, stored, and traded.

Rangoon’s port has been in use since the mid-eleventh century when the Mon dynasty found the area. It remained a small fishing village referred to as “Dagon” until the mid-1700s when it was captured by the Konbaung dynasty who renamed the village Rangoon and modified the waterfront into a port. Prior to its colonial occupation the port city was already well known for its ship building, wood exports, and a growing, diverse population.[9] In the beginning of colonial Rangoon the port was run by a Master Attendant and Town Magistrate who managed shipping, fees, and up keep. In 1878 municipal officials created a Port Trust run by the Secretary to Government and managed by Commissioners. This model was based off a similar colonial governing body created in Calcutta (Kolkata) under Bengal Act V of 1870.[10] By the late 19th century trade increased significantly around the globe and Rangoon’s port was barely keeping pace. This led to extensive public works to build deep-water wharves for larger transport ships. In 1905 the Government sanctioned the Rangoon Port Act which significantly increased the power of Port Commissioners and by 1914 the Port Trust had its own police department (as well as engineers, traffic control, and river conservancy) and was in administrative control of 80-84% of Burma’s global trade.[11] The increase in departmental size is the cause of increased global trade and likely reason for construction of the 1928 Port Trust Office; however the increase in policing and authority is more likely in response to the rising tensions of between displaced immigrants and dispossessed Burmese.

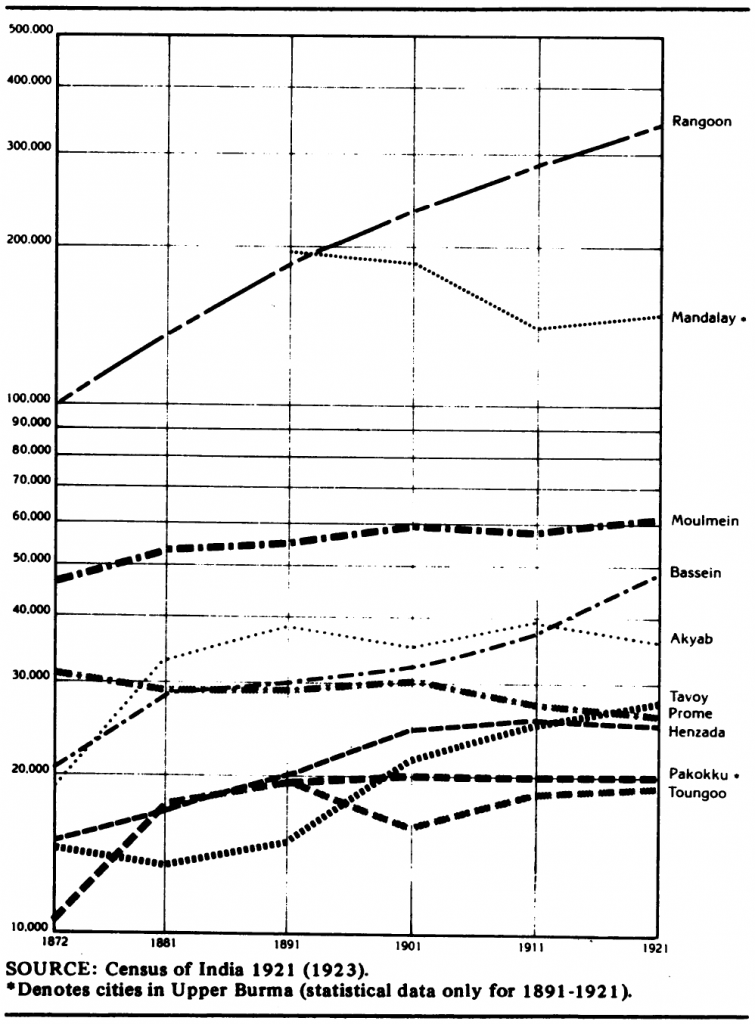

Colonial occupation of Rangoon and its port brought an influx of Indian immigrants. Migrants from India accounted for 78% of the city’s population growth between 1872 to 1901 and made up half the population c.1891.[12] “By 1918, some 300,000 manual workers (“coolies”) arrived in Rangoon from India annually, making the colonial capital the world’s second-largest destination for immigration, after New York.”[13] At the same time overcrowding became a formidable issue throughout the city and in 1921 the government launched the Rangoon Development Trust (RDT) with the committee’s vision to fix the city’s social issues.

The RDT ignored the overcrowding issues of Indian port labourers because the convenience of their location was a “necessary evil” to bare for the time being. The Burmese, on the other hand, were disproportionately displaced out of the city; through the clearance of slums and setting of high rents. These displacements took place throughout the 1920s and the RDT didn’t start building any public housing until the end of the decade and entrusted the private sector to build housing for the labourers.[14] Although this displacement has little to do with the actual Port Trust Office, the immigration trends and subsequent racial tensions are vital in its understanding as a port city and the growing power of authority.

[1] Noriyuki Osada, “Housing the Rangoon Poor : Indians, Burmese, and Town Planning in Colonial Burma,” IDE Discussion Papers, IDE Discussion Papers (Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization(JETRO), March 1, 2016): 4, https://ideas.repec.org/p/jet/dpaper/dpaper561.html.

[2] Sarma and Sidaway, “Securing Urban Frontiers: A View from Yangon, Myanmar,” 455

[3] Ibid., 455

[4] Seekins, “The rise and fall of British Rangoon, 1824-1941,” 30, 32

[5] Elly Win, Enkhtsetseg Ganbat, and Nam Kichan, “Port Governance Structure: the Port of Yangon,” KMI International Journal of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries 7, no. 1 (June 2015): 4

[6] Yda Saueressig-Schreuder, “The Impact of British Colonial Rule on the Urban Hierarchy of Burma,” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 10, no. 2 (1986): 255

[7] Seekins, “The rise and fall of British Rangoon, 1824-1941,” 30

[8] Saueressig-Schreuder, “The Impact of British Colonial Rule on the Urban Hierarchy of Burma,” 256-262

[9] Ian Morley, “Rangoon,” Cities 31 (April 1, 2013): 601–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.08.005.

[10] G. C. Buchanan, “THE PORT AND CITY OF RANGOON,” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 62, no. 3207 (1914): 535-6

[11] Ibid., 535-537

[12] Osada, “Housing the Rangoon Poor: Indians, Burmese, and Town Planning in Colonial Burma,” 5-6

[13] Seekins, “The rise and fall of British Rangoon, 1824-1941,” 40

[14] Osada, “Housing the Rangoon Poor: Indians, Burmese, and Town Planning in Colonial Burma,” 9-14

Port Trust Office

Regarding architecture and design, Rangoon’s central business district was extensively redeveloped and replaced by colonial utilitarian buildings constructed of masonry. Unlike the extant bamboo and wood dwellings, these new buildings would convey British solidarity and colonial permanence.[1] The late-nineteenth to early-twentieth century brought further redevelopment of its public buildings, including the Port Trust Office, and was favoured by colonialists: “it is unfortunate that, with rare exceptions, the buildings are devoid of any architectural merit […] the advent of [a] Government architect and several good architects in private practice has made it possible to erect structures that are not an offence to the eye owing to their lack of any style or combination of all styles.”[2] The construction of the Port Trust Office is one such colonial invention. Designed by the former consulting architect for the British-Burma Government, Thomas Oliphant Foster (in partnership with Basil Ward).[3]

Described in a Times of India article, the new Port Trust Office was completed in September of 1928 “in the Renaissance style with an imposing tower 165 feet high.”[4] Located at the northwest corner of a prominent intersection, the building presents domineering façades on the north side of the shore and east of the Account-General’s Office. Its stylistic influences are Renaissance and Neo-classical and display Indo-Saracenic elements on the west façade such as the jali screens.[5] It’s a steel frame construction on concrete piles and required the transport of 956 tons of steel to complete.[6] From photos, there doesn’t seem to be any coursing or mortar joints so it’s difficult to what exactly the building’s veneer is (Plaster? Parging? Stucco?); smaller ornamentation is likely made of cast iron or glazed terracotta. The building’s tower is the most intrusive element on the landscape; it’s one of the tallest structures on the waterfront which makes it the first building travellers and traders see when arriving in Rangoon.[7] The architectural style, material palette, siting, and tower are all measures the colonists took to reinforce British Imperialism in Burma. The styles of Europe were more sophisticated (in their opinion) and needed to be reflected in their colonies; the use of steel and concrete was preferred over wood which favoured British steel exports; and its siting at a prominent corner on the waterfront gave it high visibility to incoming port traffic, creating a colonial narrative of British imperialism before one enters the city.

Since is construction, the administrative body of the Port Trust remained unchanged by its colonial framework until 1972 when it was granted sole authority in managing all of Burma’s International and coastal trade. When the country’s name changed from Burma to Myanmar in 1989, the administrative body was also renamed the Myanma Port Authority, and in 1997 the port’s banking sector was privatized.[8] In its contemporary context, the Yangon port is Myanmar’s only international port and controls around 90% of the country’s imports and exports to date.[9] The Port Trust Office and its administrative body today inherited a colonial governance structure that was expanded by the Military Dictatorship by way of consolidating authority over all ports and controlling the economy.

[1] Seekins, “The rise and fall of British Rangoon, 1824-1941,” 34-35

[2] Buchanan, “THE PORT AND CITY OF RANGOON,” 533

[3] Guedos, “Behind the Veils of Modern Tropical Architecture,” 7

[4] “Rangoon Port Trust: New Offices Completed,” The Times of India (1861-Current), September 6, 1928.: 14

[5] Ibid., 14; These were constructed of glazed terracotta and provide ventilation while keeping out rain.

[6] Ibid., 14

[7] Note: The tower’s composition is similar to St Mark’s Campanile in Venice which functions similarly as a guiding port landmark but uses its belfry for bells and not a lookout.

[8] Win, Ganbat, and Kichan, “Port Governance Structure: the Port of Yangon,” 5; Mu Mu Han, Guo Long Lin, and Bin Yang, “Classification of the Yangon’s Ports in Myanmar with Efficiency Measurement by Using DEA,” Advanced Materials Research 204–210 (2011): 193–96,

[9] Win, Ganbat, and Kichan, “Port Governance Structure: the Port of Yangon,” 1, 4

Conclusion

Yangon’s historical context under British colonial rule is essential in understanding the events leading up to the construction of the Port Trust Office. The colonialist’s commercial ambitions for the port, city, and country would intend to solidify the eastern India borders and complete the Imperial economic relationship of exporting raw materials and commodities while importing manufactured goods. The Port Trust Office, looming in colonial symbology and placement, remains a beacon of British Imperialism; still sole authority of the country’s economic trade.

Bibliography

Baillargeon, David. “‘On the Road to Mandalay’: The Development of Railways in British Burma, 1870–1900.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 48, no. 4 (July 3, 2020): 654–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2020.1741838.

Buchanan, G. C. “THE PORT AND CITY OF RANGOON.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 62, no. 3207 (1914): 531–46.

Egreteau, Renaud. “Power, Cultural Nationalism, and Postcolonial Public Architecture: Building a Parliament House in Post-Independence Myanmar.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 55, no. 4 (October 2, 2017): 531–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2017.1323401.

Guedos, Pedro. “Behind the Veils of Modern Tropical Architecture.” Docomomo International (blog), January 21, 2021. https://www.docomomo.com/articles/behind-the-veils-of-modern-tropical-architecture.

Han, Mu Mu, Guo Long Lin, and Bin Yang. “Classification of the Yangon’s Ports in Myanmar with Efficiency Measurement by Using DEA.” Advanced Materials Research 204–210 (2011): 193–96. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.204-210.193.

Jarvis, Andrew. “‘The Myriad-Pencil of the Photographer’: Seeing, Mapping and Situating Burma in 1855*.” Modern Asian Studies 45, no. 4 (July 2011): 791–823. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X09990023.

Kusno, Abidin. Southeast Asia : Colonial Discourses. The Routledge Handbook of Planning History. Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315718996-17.

Lewis, Su Lin, ed. “Asian Port-Cities in a Turbulent Age.” In Cities in Motion: Urban Life and Cosmopolitanism in Southeast Asia, 1920–1940, 47–94. Asian Connections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316257937.003.

Middleton, John. World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge, 2015. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315698014.

Morley, Ian. “Rangoon.” Cities 31 (April 1, 2013): 601–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.08.005.

Osada, Noriyuki. “Housing the Rangoon Poor: Indians, Burmese, and Town Planning in Colonial Burma.” IDE Discussion Papers. IDE Discussion Papers. Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization(JETRO), March 1, 2016. https://ideas.repec.org/p/jet/dpaper/dpaper561.html.

“Rangoon Port Trust: New Offices Completed.” The Times of India (1861-Current). September 6, 1928.

Sarma, Jasnea, and James D. Sidaway. “Securing Urban Frontiers: A View from Yangon, Myanmar.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44, no. 3 (2020): 447–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12831.

Saueressig-Schreuder, Yda. “The Impact of British Colonial Rule on the Urban Hierarchy of Burma.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 10, no. 2 (1986): 245–77.

Seekins, Donald. (2011). “The rise and fall of British Rangoon, 1824-1941” State and Society in Modern Rangoon (1st ed.). Routledge (2011): 28-46 https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.4324/9780203610794

Sugarman, Michael. “Reclaiming Rangoon: (Post-)Imperial Urbanism and Poverty, 1920–62.” Modern Asian Studies 52, no. 6 (November 2018): 1856–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X17000440.

Win, Elly, Enkhtsetseg Ganbat, and Nam Kichan. “Port Governance Structure: the Port of Yangon.” KMI International Journal of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries 7, no. 1 (June 2015): 1–15.

Illustration Credits

Cover Photo: West façade of Port Trust Office, https://www.yangongui.de/myanma-port-authority/

Figure 1: Noriyuki Osada, “Housing the Rangoon Poor : Indians, Burmese, and Town Planning in Colonial Burma,” IDE Discussion Papers, IDE Discussion Papers (Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization(JETRO), March 1, 2016): 22

Figure 2: Saueressig-Schreuder, Yda. “The Impact of British Colonial Rule on the Urban Hierarchy of Burma.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 10, no. 2 (1986): 263.

Figure 3: Yda Saueressig-Schreuder, “The Impact of British Colonial Rule on the Urban Hierarchy of Burma,” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 10, no. 2 (1986): 266

Figure 4: The colonnaded front facing Strand Road is now being obscured by a concrete overpass, https://www.yangongui.de/myanma-port-authority/

Figure 5: One rare access point to the river is the jetty at the bottom of Pansodan Street, where Dala-bound ferries dock, https://www.yangongui.de/yangons-waterfront-a-city-with-a-view/