Figure 1. Tourists sit outside the Palm House by the flower beds at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew in London.

The Palm House: a crucial node in the 19th century colonial world

The Palm House at Kew Gardens is an exemplar of industrial modernity. The building helps to encapsulate ideas of industrial modernity with its size, materials and meaning. With the building’s large-scale use of glass and wrought iron it helps situate the project in the 19th century where these building materials became more widely used.1 The Palm House was designed by Decimus Burton and Richard Turner and was one of the largest greenhouses in the British Empire when it was created from 1844 to 1848.2 The building epitomized the desire to rule natural processes using artificial means.3 The project was the locus of plant knowledge, information and cataloguing in the British Empire in the 19th century.4 By examining the Palm House through its relationship of colonial power and botany it can be seen that the project was used as an economic, scientific and cultural tool to exert dominance over the colonial regions of the British Empire. The Palm House was crucial in transforming knowledge into power and profit for Great Britain.5 Furthermore, it was key in disseminating specified plant knowledge through magazines and journals to the public, it brought wealth to the empire by selecting the plantation crops to cultivate and it acted as a training space for aspiring gardeners and horticulturalists.6 The Palm House is a vital node in the colonial world that helps to showcase Britain’s mastery of colonized people, their lands, and their ecosystems.7As well it highlights how Britain was a strong hegemonic force conquering over a large part of the world in the 19th century.8

Figure 2. Visitors on balcony, viewing the diversity of plant life at the garden.

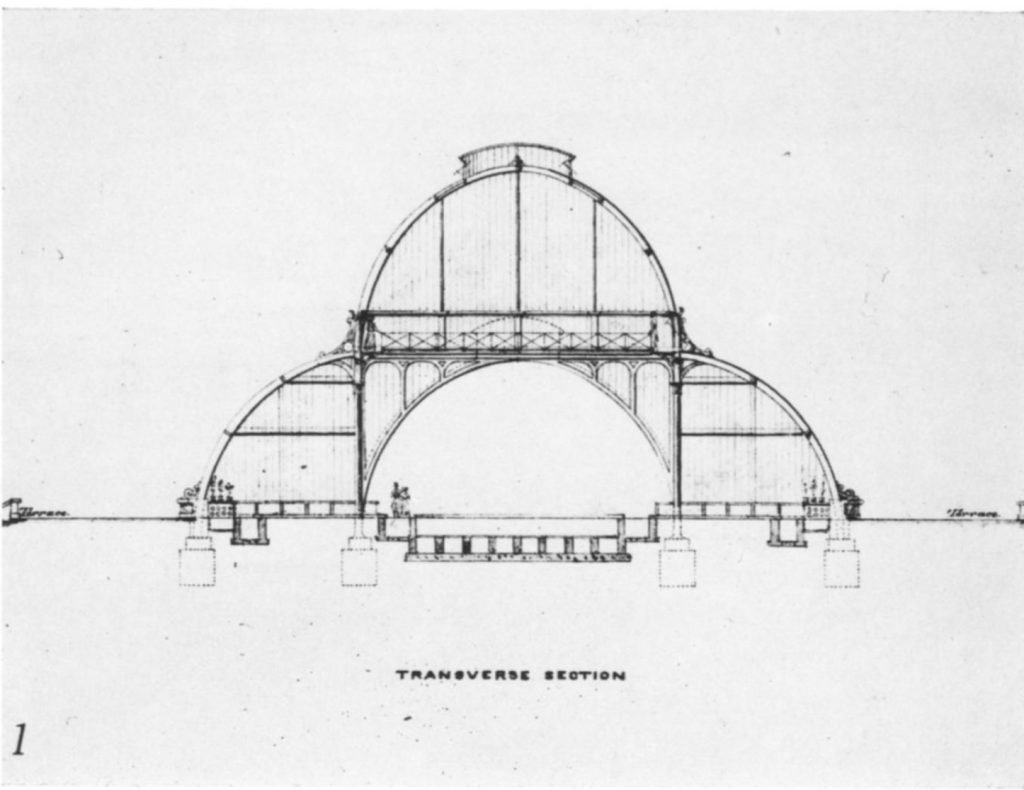

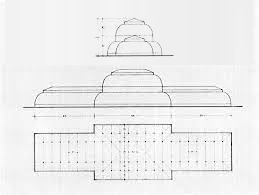

In the 19th century there was a large expansion in the use of glass as a building material and new methods for making glass were also introduced.9 The Palm House at Kew Gardens embodies this era of material production and it was built with large amounts of glass and wrought iron.10 The building is 362 feet long, 100 feet wide and 66 feet high at the center and 30 feet at the wings.11 The main ribs and ties are made of wrought iron and the whole building is covered with 45,000 feet of sheet glass.12 Iron posts are inserted into massive granite blocks, which are hollow and conduct the rain from the glass roof to the underground cisterns placed around the whole building.13 The building is heated with hot water pipes, having about 28,000 feet of surface and a length of 5 miles.14 The pipes are connected to several boilers laid under the perforated iron flooring which forms the paths of the interior.15 Furthermore there are multiple iron spiral staircases, that give the visitor an opportunity to look down at the activity below.16 “A conventional style suitable for horticultural purposes is adopted and the classic and ecclesiastical is avoided, and all extraneous ornaments are dispensed with.”17 The approach to building the Palm House with glass and wrought iron helped to highlight the ingenuity of Burton and Turner and in a period of industrial modernity this project emphasized some of the prevailing ideas of the era with technological innovation, progress, and efficiency.18

Figure 3: Transverse Section of the Palm House.

The Palm House was an important part of the British Empire in the 19th century that helped disseminate information about gardening and horticulture to a large audience as it begun to rise to prominence in the public.19 In the 19th century there was an emphasis on colonial botany.20 The Palm House and the Kew Gardens was a depot for the interchange of plants throughout the empire.21 Britain had colonies in both wet and dry environments, down at sea level and up in the Himalayas.22 The plants at the Palm House could be altered varieties of seeds grown in various colonial regions and in foreign climates.23 Plant transfer is an old practice but in the 19th century it had never before been undertaken on such a large scale.24

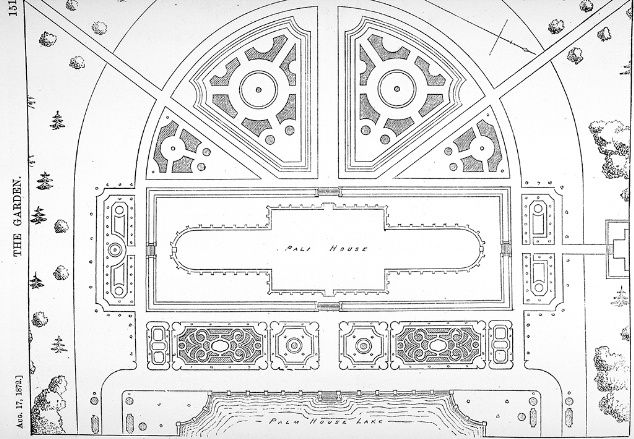

Figure 4. Flower Garden Plan of landscaping placed around the Palm House.

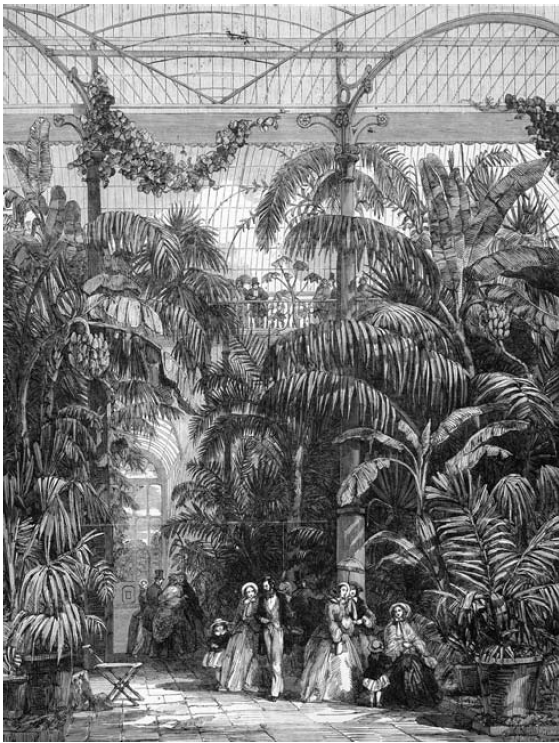

The Palm House and greenhouse culture helped to mark a shift from agriculture to horticulture.25 Horticultural glasshouses reaffirmed Britain’s triumph over geographical forces by relocating foreign climates from across the British Empire.26 Artificial indoor environments were modeled on and even interpreted as foreign climates which was well understood by horticulturalists.27 Entering the Palm House there was an abrupt environmental change that included changes in light, temperature, humidity, and flora.28 This allowed Britons stepping into the Palm House to be transported to a different part of the world where even the air one breathed was felt to be foreign. “The air is filled with the aromatic leaves of cinnamon and camphor… one is met with palm trees 40 feet high, sugar canes, clusters of golden bananas hanging across the walks and tree ferns with plume like heads.”29 In the Palm House collections of plants were grouped from specific regions and were acclimatized to different parts of the world.30 The Palm House could be thought of as a simulacrum of Britain’s tropical colonial empire represented in the microclimates and atmosphere within the greenhouse.

Figure 5. The image describes the relative scale of the plants in relation to the visitors who are strolling through the building. It also showcases the building structure can be seen towards the top of the image.

Figure 6: Elevation and Plan view of the House

Colonial Influence of the British Botanic Garden Network

In the 19th century advances in communications allowed scholars and scientists to exchange, codify and preserve information and build upon a useful base of knowledge in relation to plant life, seeds and botany.31 In this century western scholars and scientists performed experiments, published their proceedings received reports from travelers all over the world and disseminated new information.32 The British botanic garden network played a critical role in generating and distributing useful scientific knowledge.33 This facilitated transfers of energy, manpower and capital on a worldwide basis at an unprecedented scale.34 The Palm House undertook plant transfers and scientific plant development that resulted in new plantation crops for the tropical colonies.35 This altered the patterns of world trade and led to increased human energy in the form of underpaid labor, that the European core extracted from the tropical peripheries of the world system.36 This was not only present in Britain, the Belgians, and the Portuguese each had a botanic gardens solely devoted to developing tropical plants for the benefit of their colonial planters.37 Botanists often had the ability to suggest where to find plants that would be able to fill a demand at the time, along with how to improve the plant through species selection and hybridization.38 Furthermore, they would need to know how to cultivate the plant with cheap colonial labor and how to process the plant for the world market.39This expertise and understanding of plant life allowed botanists to play a major role in making a colony a viable and profitable part of the empire.40 2 key examples of botanists selecting plants that ended up changing the world market include cinchona and rubber.41 In both cases a plant indigenous to Latin America was furtively transferred to Asia for development by Europeans.42 Independent Latin American states including Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Ecuador each lost a native industry as a result of these transfers.43 Asia acquired these plants only geographically; the actual benefits went to Europe.44 This helps to describe the hegemonic force of the colonial powers particularly with Britain and institutions such as the Palm House, where they were able to subvert national power and authority structures.45 This describes how the network of plant interchange and colonial botany penetrated nearly all societies on a worldwide scale completely ending domestic industries and forcibly moving large amounts of plant life for scientific development and experimentation and more broadly the economic gain of colonial empires.46

The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew were the nerve center for all the British colonial botanic stations.47 The Palm House was important in helping coordinate the efforts of the many gardens in the British colonies and dependencies such as Calcutta, Bombay, Mauritius, and Trinidad.48 A plant such as cinchona from the tropical Andes had pertinency in the colonial world and was smuggled from South America to be grown on Indian plantations.49European scientific expertise ,capital and political power had driven a native industry off the market in favor of a vast plantation-based industry completely controlled by Europeans.50 British capital was movable, and the plants were transferable. In South America labour was scarce, while in Southeast Asia labour was in abundance.51 The British simply moved the plants to a labor abundant area under their direct political control in order to maximize efficiency and economic gain.52 The price of many products and crops coming from colonial regions had been kept low through economic and political pressure exerted by the metropolitan core and did not reflect the true costs of production in human energy.53 Consumers in developed countries have often benefitted from the underpaid labor of East Africans, Yucatan Indians, Brazilian peasants, and Indonesians.54 Sugar, coffee, tea, cocoa, cinchona and rubber all have similar histories of labor exploitation.55 This extraction of human energy from colonial areas of the world has been one of the sources of wealth necessary to underwrite the budgets of western scientific stations such as the Palm House.56

Conclusion

The Palm House at Kew Gardens is a key example of industrial modernity in the 19th century. Its size, material and meaning were all directly linked to the cultural period it was created. The project was a vital node in the colonial world transforming knowledge into power and profit for Great Britain.57 The Palm House was a key player in the 19th century British cultural era and it played an active role in the British Empire through scientific expertise, plant knowledge and information.58 By examining the Palm House through its relationship of colonial power and botany it can be seen that the project was used as an economic, scientific and cultural tool to exert dominance over the colonial regions of the British Empire. The relationship of science, capital and political power shown by the Palm House at Kew Gardens had direct impacts on colonized people, lands and ecosystems that are still evident in our present day.59

Notes

1 R.G.C. Desmond. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens? “(Kew Bulletin 27, no. 2 1972), 295.

2 The Great Palm House at Kew (Friends’ Intelligencer1853), 333.

3 R.G.C. Desmond. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?”, 295.

4 Desmond, 299.

5 Lucile H, Brockway. “Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens.” (American Ethnologist 6, no. 3 1979), 450.

6 Brockway. “Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens,” 450.

7 Brockway ,450.

8 Brockway ,450.

9 R.G.C. Desmond. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?”, 300.

10 “The Great Palm House at Kew.” (The Genesee Farmer 1856), 374.

11 “The Great Palm House at Kew.”, 374.

12 “The Great Palm House at Kew.”, 374.

13 “The Great Palm House at Kew.”, 374.

14 “The Great Palm House at Kew.”, 374.

15“The Great Palm House at Kew.”, 374.

16“The Great Palm House at Kew.”, 374.

17 R.G.C. Desmond. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?”, 299.

18 Desmond, 300.

19 Brockway. “Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens,” 450.

20 Brockway, 451.

21Brockway, 451.

22 Brockway, 451.

23 Brockway, 452.

24 Brockway, 452.

25 Dustin, Valen. “On the Horticultural Origins of Victorian Glasshouse Culture.” (Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 2016), 407.

26 Valen ,”On the Horticultural Origins of Victorian Glasshouse Culture,” 407.

27 Brockway. “Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens,” 452.

28 Brockway, 453.

29 Brockway, 453.

30Valen ,”On the Horticultural Origins of Victorian Glasshouse Culture,” 406.

31 Brockway. “Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens,” 454.

32 Brockway, 454.

33 Brockway, 454.

34Brockway, 455.

35 Brockway, 455.

36 Brockway, 455.

37 Brockway, 455.

38 Brockway, 455.

39Brockway, 456.

40 Brockway, 456.

41 Brockway, 459.

42 Brockway, 459.

43 Brockway, 459.

44 R.G.C. Desmond. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?”, 299.

45 Brockway, 459.

46 Brockway, 459.

47 Brockway, 459.

48 Brockway, 460.

49 Brockway, 460.

50 Valen ,”On the Horticultural Origins of Victorian Glasshouse Culture,” 407.

51 Brockway, 460.

52Brockway, 460.

53 Brockway, 460.

54 Brockway, 460.

55 Brockway, 460.

56Brockway, 460.

57 Brockway, 461.

58 Brockway, 461.

59 Brockway, 461.

Bibliography

Brockway, Lucile H. “Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens.” American Ethnologist 6, no. 3 (1979): 449-65. Accessed April 23, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/643776.

Desmond, R. G. C. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?” Kew Bulletin 27, no. 2 (1972): 295-303. Accessed April 24, 2021. doi:10.2307/4109457.

“The Great Palm House at Kew” Friends’ Intelligencer (1853-1910), Aug 13, 1853, 333, https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/magazines/great-palm-house-at-kew/docview/91219957/se-2?accountid=14656.

“The Great Palm House at Kew.” The Genesee Farmer (1845-1865), 12, 1856, 374, https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www- proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/magazines/great-palm-house-at-kew/docview/126171045/se-2?accountid=14656.

Valen, Dustin. “On the Horticultural Origins of Victorian Glasshouse Culture.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 (2016): 403-23.Accessed April 24, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26418938.

Images

Figure 1. Alfredo Caliz. Tourists Sit outside the Palm House by Flower Beds at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew in London. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.12187903.

Figure 2. Alfredo Caliz. Tourists Look at Various Plant Species inside the Palm House at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew in London. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://jstor.org/stable/10.2307/community.12198065.

Figure 3. Kew Bulletin. Tranverse Section of the Palm House. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4109457

Figure 4. Kew Bulletin. Flower Garden Plan of landscaping placed around the Palm House. Accessed April 23, 2021. Palm-House-plan45-we_634.jpg (634×439) (bdonline.co.uk)

Figure 5. Illustrated London News no.572. Interior Perspective of the Palm House. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26418938

Figure 6. Edward J. Diestelkamp. Elevation and Plan view of the Palm House. Accessed April 20, 2021.DOI: 10.1080/01445170.1982.10412406