The city of Jakarta began its story from the Dutch traders that arrived in the island in their conquest of finding precious spices. The Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, commonly known as the VOC or Dutch East India Company, landed on what was then Jayakarta in 15951. The archipelago of modern Indonesia was a melting pot of cultures and diversity, filled with merchants, missionaries, and adventurers coming from India, China, and the Arab countries2. Between the Europeans, the Dutch were latecomers, with the Spaniards, English, and Portuguese setting foot first on the island3. However, it was the Dutch, under the institution of the Dutch East India Company, who eventually exerted power over the locals and claimed the island as part of their territory. The 300-year-long colonisation of the Dutch officially began with the establishment of the new colonial city of Batavia, taking over the existing city of Jayakarta. With the diverse population of Batavia, the Dutch, performed measures to ensure their dominance over the local society. This essay will explore the colonial city of Batavia and examine how the built environment of the city was used in imposing social order and maintaining colonial dominance over the local population.

The Dutch East India Company founded the city of Batavia in 16194 organising a central trading hub of the company in Asia. To beat out European competitors, The Dutch East India Company was very ambitious in establishing themselves in the theatre of world trade. The company was started by the Dutch government in 1602 in response to successes in private trading efforts and in an attempt to manage prices of goods5. Institutionalising the private trade companies into a government controlled monopoly allows the Dutch to control the European market6. Looking to dominate the world trade, the Dutch are not looking for land acquisition. This facade allows the Dutch to build exclusive relationships with the local merchants and build warehouses and outposts around the city port7. The Governor-General, Jan Pietersz Coen, recognises that building an administrative capital on the island would be efficient for trade8, as having the location under the company’s control would allow the Dutch to oversee the traffic passing through the Sunda Strait, a major route in the archipelago9. This realisation became key in the development of Dutch dominance in the area, and the building of the colonial city of Batavia.

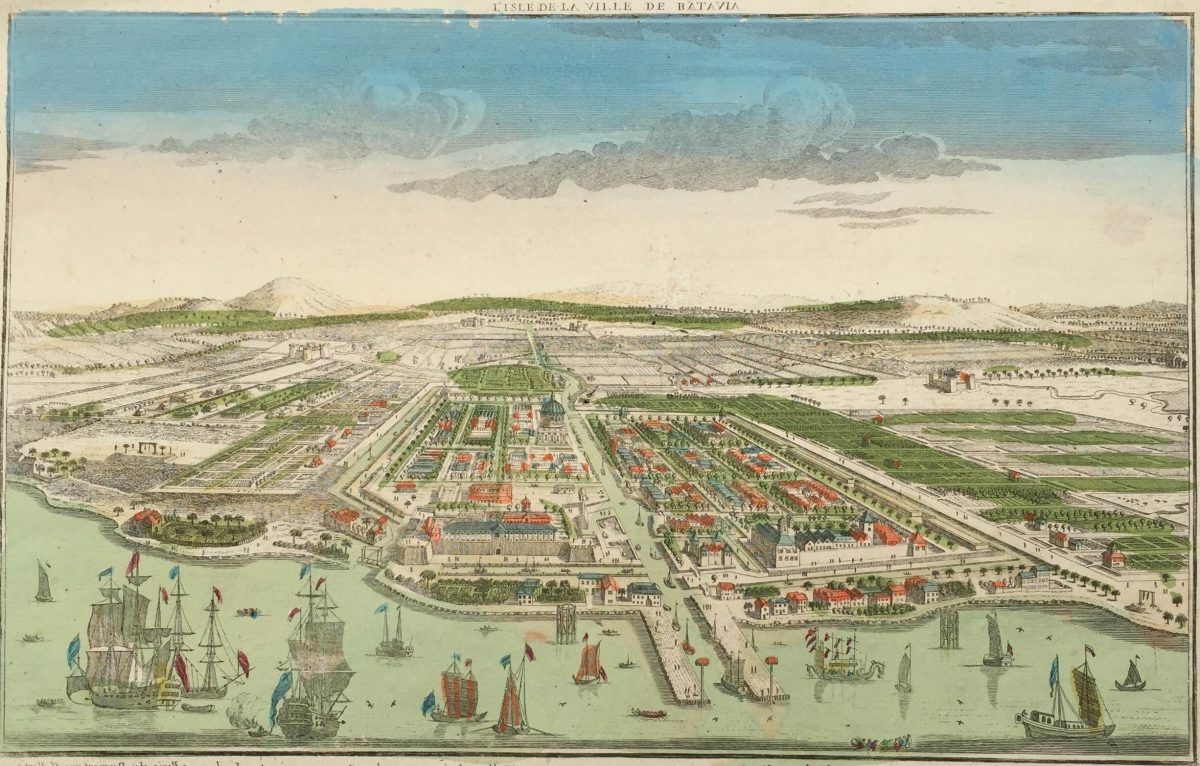

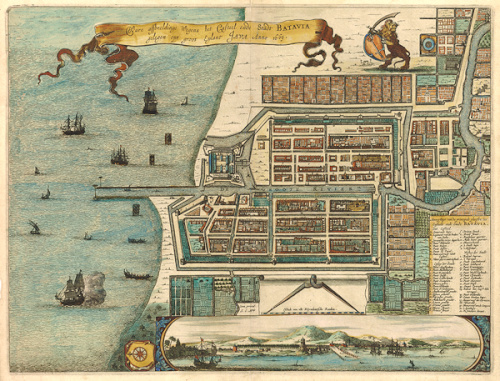

The site of Batavia was already an acknowledged trading centre, populated by the local, Chinese, Arab, English, and Portuguese merchants. However, through exploitations of the region’s political instabilities, the Dutch were able to take over the city and gained control10. The establishment of Batavia was the marking of Dutch colonisation in the area, and the beginnings of Eurocentrism in the region. The newly built city follows seventeenth-century Dutch urban planning principles that orders urban zones into a hierarchy headed by the Dutch and serving the interests of the Dutch East India Company11. The city was completed as a walled city with canals running through the centre and out. The eastern part of the walled city seems to have a more even distribution of canalling system compared to the other half, where there are more roads and have smaller block divisions, but lacks canals. This suggests a difference in accessibility to different parts of the city by road and water. Additionally, the city possesses a rectilinear shape and grid pattern that is characterised as distinctly Dutch. The creation of Batavia to look and feel Dutch was intentional to reinforce the continuously challenged status of the dutch by the diverse population in the area12. Having a familiar built environment that would recall the landscape of their home became one of the ways that the Dutch maintained their identity and dominance in the island

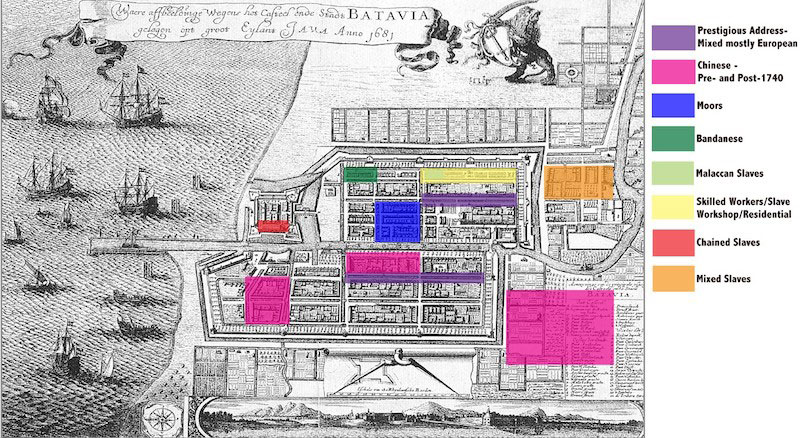

The Dutch Batavians were a small group in comparison to the larger population. In solidifying their rule over the substantial population, they imposed subtle measures to gain control over the city. By masking as “traders” and not colonialists, they were able to conceal their dominance through implementations of place-making strategies that would allow social division to develop unconsciously rather than through objective regulation13. The structure of Batavia was meant to segregate the city’s population and inflict social stratification that served colonial needs. The plan of the city implemented barriers to movement that classified Batavians into categories of ethnicity with different levels of mobility within the city. The walls of the city acted as a blockage to the marginalised populations that were forcibly moved outwards. Initially intended to protect the city from outside threats, the walls became an internal protection barrier as the enslaved population were deemed dangerous14. This initiative was the Dutch’s way of controlling and managing the population of Batavia. Moreover, canals also became a hindrance in the city as it was not provided with sufficient bridges on certain areas15. Although the canals provided access through water, the lack of land infrastructure that connects the separated land on some districts limits mobility through roads. As Batavia’s residences are not evenly distributed, the disjunctures became blockages that separated populations within the city. Manifested through infrastructure, the smaller Dutch community was able to maintain control over the larger population, demonstrating superiority and dominance over the area.

The built environment became key in manifesting social behaviour in Batavia. Through characterising the city as Dutch, distinctly grouping population through their ethnicity, creating wall barriers, and controlling accessibility within the city, the Dutch were able to exert their colonial dominance over the larger population, imposing segregation and social stratification. The preservation of hierarchy between racial groups through place-making protected Dutch power over the Batavians and strengthened their identity in the tropical archipelago. Although subtle, the master plan for Batavia was effective, allowing the colony to build up their 300-year-long rule over modern Indonesia. The case of Batavia presents an exemplary of the role in which architecture and urban design takes part in colonialism and social discrimination. Perhaps understanding the power of the built environment in determining behaviour is a step forward in further creating a critical and analytical way of viewing architecture and history.

Footnotes

1. “Dutch Colonization,” Indonesia Imperialism, accessed April 26, 2021, https://imperialismindonesia.weebly.com/dutch-colonization.html#:~:text=The%20Dutch%20arrived%20in%20Indonesia,a%20place%20to%20take%20over.

2. “The Dutch East India Company (VOC): Indonesian Chapter ,” INDONEO, April 11, 2019, https://www.indoneo.com/en/travel/the-dutch-east-india-company-voc-indonesian-chapter/#:~:text=The%20Rise%20of%20the%20Dutch%20East%20India%20Company%20in%20Indonesia%E2%80%A6&text=By%201699%2C%20VOC%20lands%20claimed,the%20lucrative%20markets%20of%20Europe.

3. Ibid.

4. Hendrik E. Niemeijer, “The Central Administration Of The VOC Government And The Local Institutions Of Batavia (1619-1811) – An Introduction,” The Archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Local Institutions in Batavia (Jakarta), January 2007, pp. 61-140, https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004163652.1-556.7.

5. F.S. Gaastra, “The Organization Of The VOC,” The Archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Local Institutions in Batavia (Jakarta), January 2007, pp. 13-60, https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004163652.1-556.6.

6. Marsely L. Kehoe, “Dutch Batavia: Exposing the Hierarchy of the Dutch Colonial City,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 7, no. 1 (2015), https://doi.org/10.5092/jhna.2015.7.1.3.

7.ibid

8. Hendrik E. Niemeijer, “The Central Administration Of The VOC Government And The Local Institutions Of Batavia (1619-1811) – An Introduction,” The Archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Local Institutions in Batavia (Jakarta), January 2007, pp. 61-140, https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004163652.1-556.7.

9. Marsely L. Kehoe, “Dutch Batavia: Exposing the Hierarchy of the Dutch Colonial City,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 7, no. 1 (2015), https://doi.org/10.5092/jhna.2015.7.1.3.

10. “Dutch Colonization,” Indonesia Imperialism, accessed April 26, 2021, https://imperialismindonesia.weebly.com/dutch-colonization.html#:~:text=The%20Dutch%20arrived%20in%20Indonesia,a%20place%20to%20take%20over.

11. Marsely L. Kehoe, “Dutch Batavia: Exposing the Hierarchy of the Dutch Colonial City,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 7, no. 1 (2015), https://doi.org/10.5092/jhna.2015.7.1.3.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14.Ibid.

15. Ibid.

Bibliography

“Dutch Colonization.” Indonesia Imperialism. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://imperialismindonesia.weebly.com/dutch-colonization.html#:~:text=The%20Dutch%20arrived%20in%20Indonesia,a%20place%20to%20take%20over.

“The Dutch East India Company (VOC): Indonesian Chapter .” INDONEO, April 11, 2019. https://www.indoneo.com/en/travel/the-dutch-east-india-company-voc-indonesian-chapter/#:~:text=The%20Rise%20of%20the%20Dutch%20East%20India%20Company%20in%20Indonesia%E2%80%A6&text=By%201699%2C%20VOC%20lands%20claimed,the%20lucrative%20markets%20of%20Europe.

Gaastra, F.S. “The Organization Of The VOC.” The Archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Local Institutions in Batavia (Jakarta), 2007, 13–60. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004163652.1-556.6.

Kehoe, Marsely L. “Dutch Batavia: Exposing the Hierarchy of the Dutch Colonial City.” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 7, no. 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.5092/jhna.2015.7.1.3.

Niemeijer, Hendrik E. “The Central Administration Of The VOC Government And The Local Institutions Of Batavia (1619-1811) – An Introduction.” The Archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Local Institutions in Batavia (Jakarta), 2007, 61–140. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004163652.1-556.7.

Images

Fig 1. ANTIQUE MAP BATAVIA BY LETI (C.1690). n.d. Bartelle Gallery. https://bartelegallery.com/shop/antique-map-batavia-by-leti/.

Fig 2. The coconut-tree-lined Tijgersgracht canal. n.d. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batavia,_Dutch_East_Indies#/media/File:AMH-5643-KB_View_of_the_Tijgersgracht_on_Batavia.jpg

Fig 3. Distribution of Population in Batavia n.d Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art. https://jhna.org/articles/dutch-batavia-exposing-hierarchy-dutch-colonial-city/