Bitumen from La Brea Pitch Lake, Trinidad to Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington D.C. 1876

Diatoms are a major group of microalgae which reside in the world’s oceans, waterways, and soils. Living diatoms make up an incredibly large portion of the Earth’s biomass, constitute nearly 50% of the organic material found in the oceans, and generate between 20 to 50 percent of the oxygen produced on the planet yearly.[1] When diatoms die, their remains are deposited at the bottom of the lakes and rivers where they lived their lives, along with other biological matter from the organisms which shared these environments. Over geologic time periods, the build up of this organic matter grows, and when subjected to the increasing pressure and rising heat of material build-up deep in the earth, these remains become transformed into a heavy, sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid substance: bitumen.

Bitumens (commonly known as asphalt) have been used by humans for various applications historically, from waterproofing of boats, baskets, and mats, to use as an adhesive or mortar in construction, dating back to at least to the fifth millennium BC.[2] Today, bitumens are used in the production of roofs, pipes, and paints, but the predominant use of asphalt is road paving, with estimates of 85% of all asphalt produced being used as the binder in asphalt concrete for roads.[3] This consumption of bitumens in road building was initially spurred by two significant occurrences. First, the European colonisation of the Americas (and critically the Caribbean) from the 16th century onwards, which exposed these colonial empires to large naturally occurring sources of bitumen,[4] and second, the development of modern paving techniques in Britain during the 18th century, using bitumen as a binder, which yielded smoother roads with decreased dust and mud production.[5]

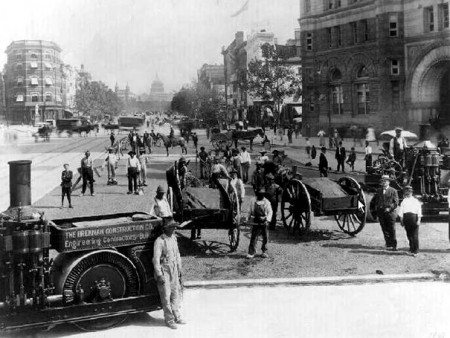

The largest natural deposit of these ancient diatoms in the world, estimated to contain 10 million tons, is the Pitch Lake located in La Brea in southwest Trinidad.[6] Trinidad was initially colonized by the Spanish from 1498 until 1797 before being occupied by the British from 1797 until 1962. During the late 19th century, as road building was becoming more prevalent around the globe, Trinidad’s Pitch lake became an ever more significant source for extraction of bitumens. The first road in North America to be paved with bitumen from the La Brea Pitch Lake was Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. in 1876, a diagonal street which connects the White House and The United States Capitol Building, before continuing into Maryland.[7]

By examining the entanglement between these two sites along the life of this material, the designed landscape of Pennsylvania Avenue and the landscape of extraction at La Brea, we can begin to gain a greater understanding of the systems of colonial commodification, the uneven systems of labour and control, and the infrastructural efficiencies which have shaped our cities, our lives, and our cultures. This approach draws from Jane Hutton’s concept of “Reciprocal Landscapes,” in which she examines material flows through various lenses in relation to sites of extraction and sites of installation. Hutton describes her process methodologically as “tracing each material, examining the unequal dynamics of exchange along its path, and probing a project’s ideological agendas alongside these material relations.”[8] By applying a similar methodology in this case, we can begin to understand the relatively abstract global power forces of capital and colonialism which brought these ancient fluid diatoms from their resting place in Trinidad to the heart of the U.S. Capital where they where solidified, and to consider the impact this journey had on the environments and communities affected along their way.

Trinidad

Human inhabitation in Trinidad and Tobago has been estimated to date back to around 4000 BCE, settled by communities from northeastern South America.[9] Many different cultural groups have inhabited the islands, chronologically from the Ortoiroid (the earliest know inhabitants), the Saladoid, the Barrancoid, the Arauquinoid, the finally the Mayoid (historically called Arawaks and Caribs), the major cultural group to inhabit Trinidad upon the arrival of European explorers.[10]

The first ever contact with Europeans was when Christopher Columbus arrived in 1498 and named the island Trinidad.[11] The Spanish colonisers largely wiped out the indigenous communities under the encomienda system (essentially a form of slavery) forcing the inhabitants to work in exchange for Spanish “protection” and conversion to Christianity. The survivors were divided into Missions and then gradually assimilated.[12]

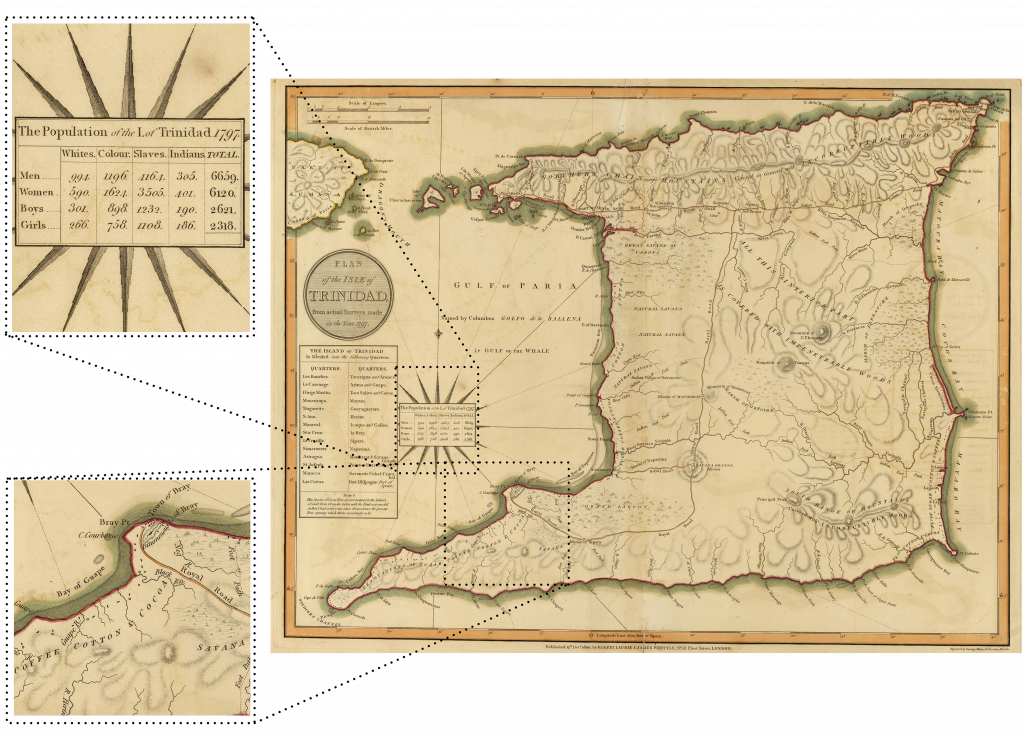

Trinidad then became a British colony from the year 1797, when the British invaded the island, until to 1962[13] During this period of occupation, Trinidad’s naturally occurring bitumen lakes and reservoirs became an ever more important asset for the British empire. By 1938, Trinidad was producing 38% of the British Empire’s oil,[14] and, in South Trinidad’s petroliferous areas, no fewer than about 9600 wells were drilled within 1,000 square miles.[15] Figure 1 shows the earliest map of Trinidad made during the British occupation. The population of the island is indicated, and the representation of the map shows that the both the people and the landscape itself was viewed as a resource by the British – with the population broken down by race, gender, and age, and extractable landscape features such as the La Brea Pitch Lake and Plantation of Sugar Coffee Cotton & Cocoa indicated abstractly in plan in relation to waterways and roads: connection infrastructure.

La Brea

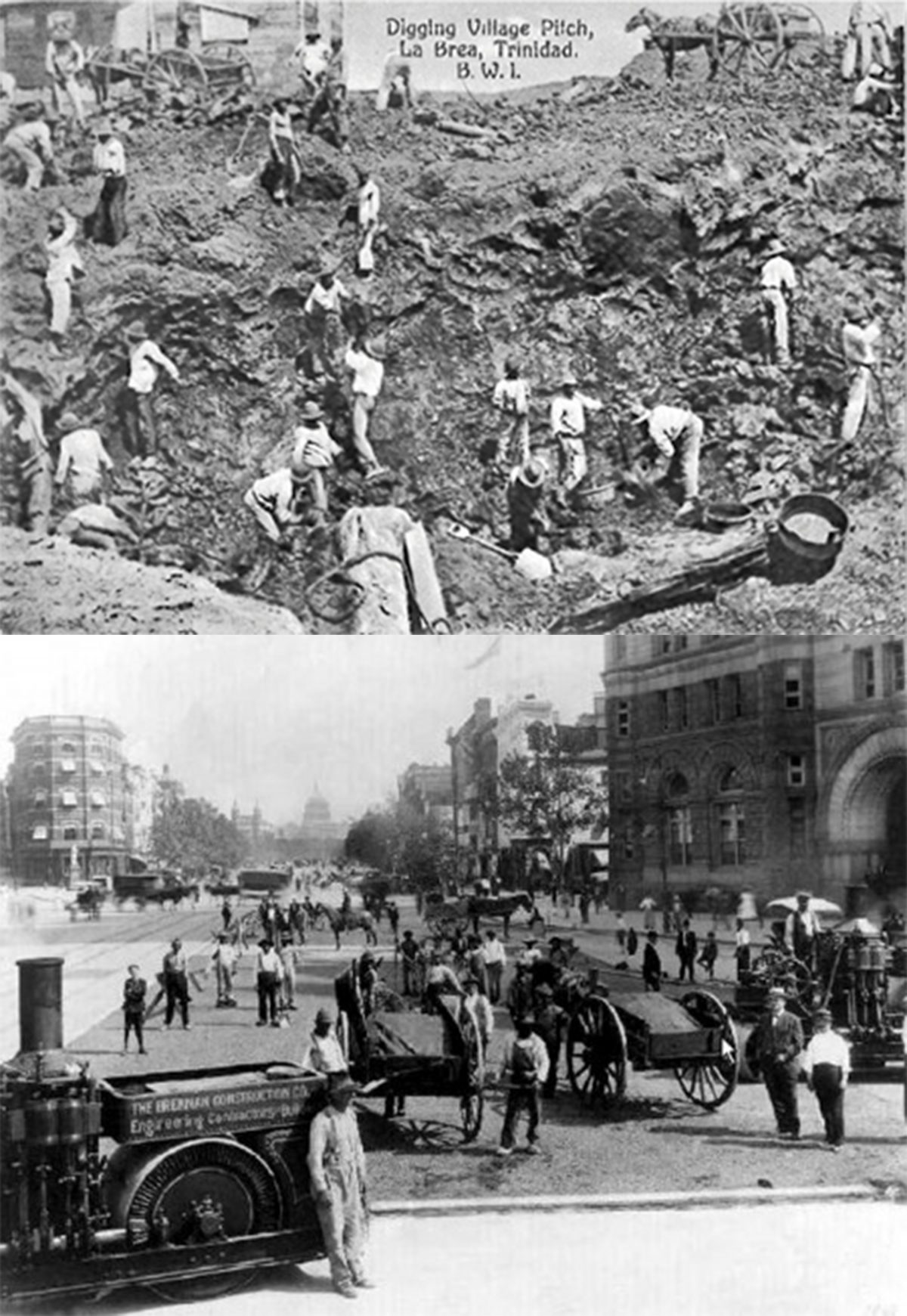

These two conceptions of people and land as resources aligned at La Brea. Figure 2 shows workers excavating pitch from the La Brea Pitch Lake in the late 19th century. The mines were operated by a demographic of natives, former African slaves, and Indians. Up until the slave emancipation which lasted from 1834 to 1838, African slaves made up the majority of the labour force in Trinidad.[16] Between 1845 and 1917, the colonial British government brought in more than 150,000 contract workers, mostly Hindus and some Muslims from India, to bolster labour power, as a response to growing demand for bitumen and loss of slave labour.[17]

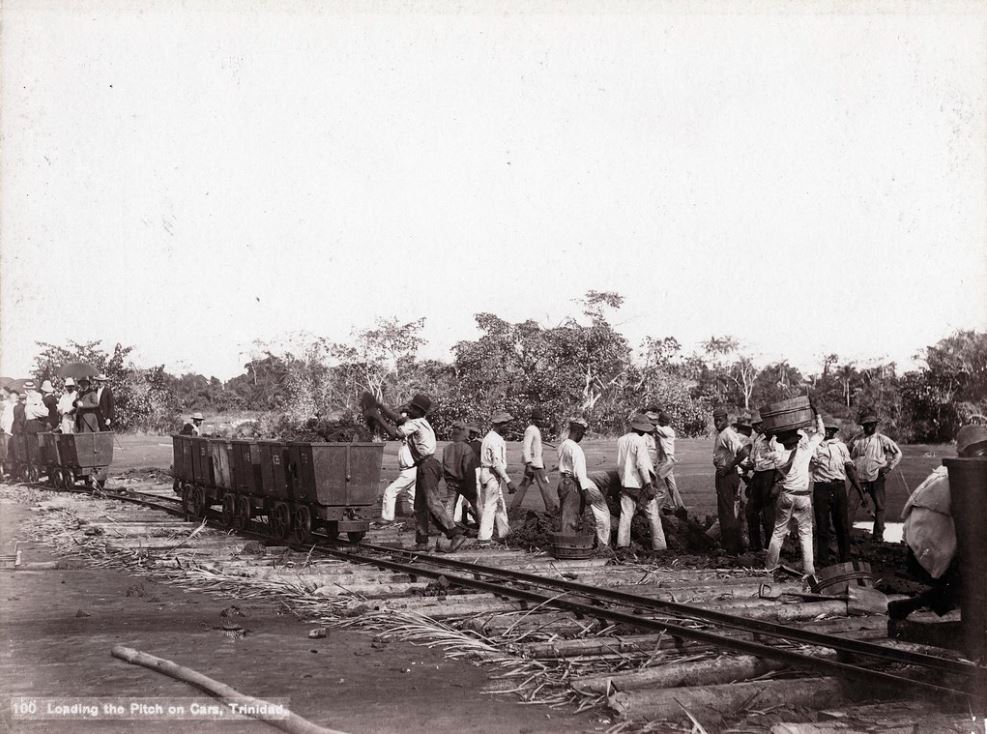

The work in the hot Caribbean climate was incredibly physically intensive. Pitch was dug by shovel and pickaxe and loaded onto wheelbarrows or small wagons, often pulled by horse, donkey, or ox. The lake itself is expansive and consists of a mixture of pools of water, bitumen and earth. The extracted bitumen varies from twenty to thirty percent soil (which does not impair the effectiveness for making asphalt pavement, since it is mixed with sand and gravel in the process– but does add additional weight, and effort in transportation).[18] As the extraction operation grew, the systems and mechanisms became more automated, using small rail cars to increase the speed of movement from the banks of the lake to the refineries (figure 3).

Figure 5 – J. Murray Jordan – Carrying Pitch From The Lake, Trinidad, 1897 https://www.flickr.com/photos/caribbeanphotoarchive/10118402564/in/album-72157608769730465/

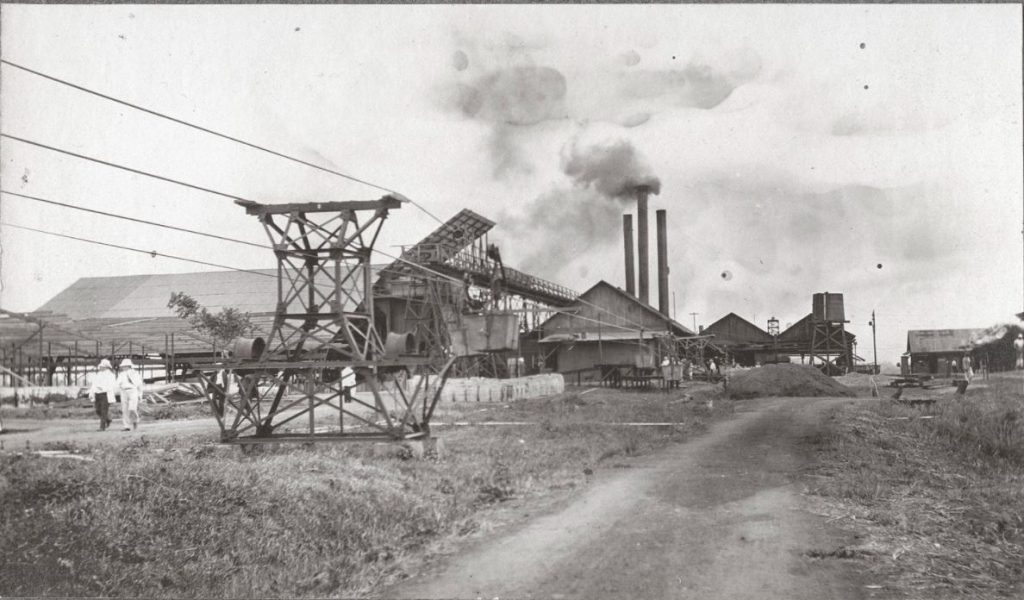

From the refinery, the pitch was moved down the hill to the coast. Initially, the ox carts carried the bitumen directly down towards the ocean to be shipped away, but again, over time this process became automated with faster suspended cable cars running directly to the pier (Figures 4 – 5). These developments increased the efficiency of the operation and quickened the rate at which the mining corporations and the British empire were able to extract exchange value from the earth. By the 1920s, more than 1,200 workers were laboring to dig up and ship away the La Brea Pitch Lake.[19]

U.S.

Across the water, the first roads in North America were beginning to be paved with bitumen from the La Brea Pitch Lake in the 1870’s.[20]

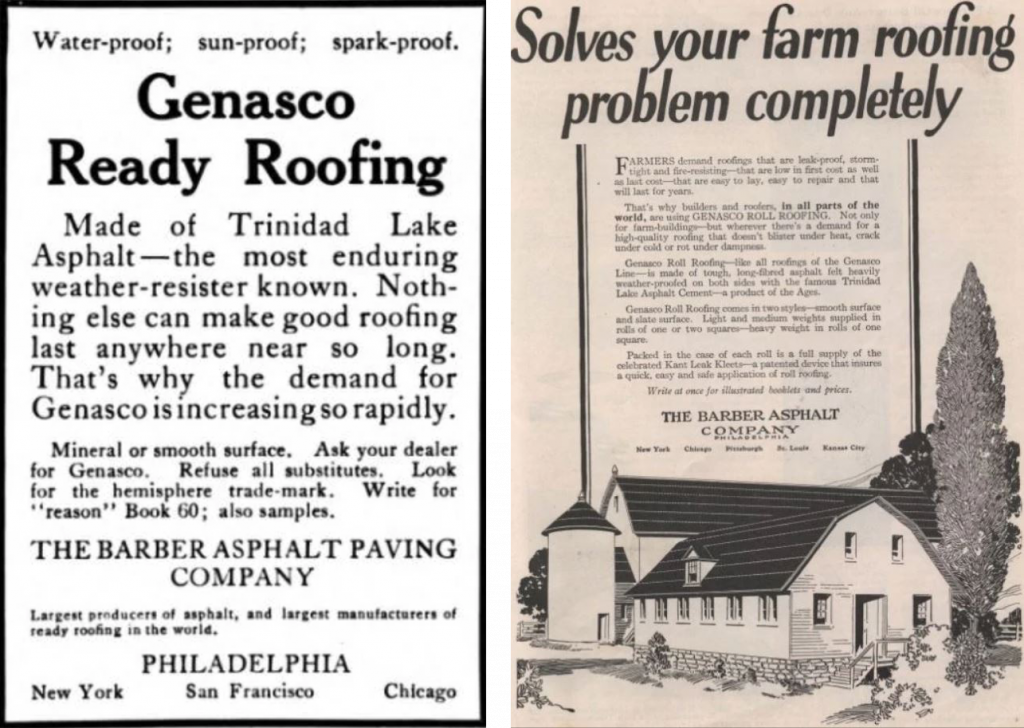

Trinidad Bitumen was widely advertised in the US during this period for other applications by the Barber Asphalt Company, especially waterproofing of roofs and ships (figures 8 and 9) but the use in paving roads began what would become one of the most significant construction and maintenance systems around the globe today: The US National Highway System.

Figure 9 – The Barber Asphalt Company Advertisement, American Builder (November 1923), https://mycompanies.fandom.com/wiki/Barber_Asphalt_Company

The portion of Pennsylvania Avenue between the White House and The United States Capital Building (paved in 1876, figure 10) holds significant historical and cultural importance in the U.S., often referred to as “America’s Main Street” and today Pennsylvania Avenue comprises part of the NHS.

Asphalt paving caught on in Britain and France during the 1850’s building upon the previous system of road building: tarmacadam roads. These roads essentially comprised of a bed of sharp-edged stones or gravel compacted by a horse drawn roller. The addition of bitumen into this mix brought added benefits of reduced dust creation during construction and use, and increased longevity and solidity, with the bitumen acting as a glue to the gravel. The process proved to be relatively cheap and easy to implement efficiently, and thus caught on. In addition, the hard asphalt didn’t soak up horse urine in the same capacity as previous wood based roads, and had no gaps between blocks or bricks for manure to become lodged in.[21] As horse travel was still predominant, asphalt quickly became equated with reduced health and sanitation hazards and thus with progress and modernisation.

The paving of Pennsylvania avenue can thus be seen as a display of progress in the heart of the U.S.’s political seat, signalling their place on the world stage. The labour and effort which went into this modernisation however was disproportionately carried by the communities of Trinidad who had little option but to mine the Tar from the La Brea Pitch Lake to support this developing industry.

Conclusion

Following the journey of these ancient diatoms from there resting place in Trinidad, carried by shovel, pickaxe, ox, ship, and horse to their new resting place in the centre of the U.S. government, and researching the global forces of power along the journey, from Colonial empires, to mining corporations, to infrastructural efficiency, and sanitation, can hopefully give us a greater understanding of the uneven histories of or world today, and the uneven impact on communities and landscapes along this journey.

This encyclopedia entry explores only one journey, but perhaps by continuing to consider the wider web of journeys and communities which make up our world, we can continue to be cognisant and critical of the choices we make and endeavoured to stay informed about the complex histories that surround us.

Endnotes

[1] What are Diatoms?. Diatoms of North America, accessed 09/04/2021, https://diatoms.org/what-are-diatoms

[2] McIntosh, Jane. The Ancient Indus Valley. ABC-CLIO, 2007, 57

[3] Bitumen Applications, Nuroil Trading, 2014, accessed 10/04/2021, https://www.nuroil.com/bitumen-applications.aspx

[4] Daintith, Terence. Finders Keepers? How the Law of Capture Shaped the World Oil Industry. Routledge, 2010, 123

[5] Vince Beiser. The world in a grain : the story of sand and how it transformed civilization. Riverhead Books, 2018, 52-53.

[6] Oishimaya Sen Nag. The unique pitch lakes of the world. WorldAtlas, 2021, accessed 09/04/2021, https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-five-natural-asphalt-lake-areas-in-the-world.html

[7] John Davis. The asphalt industry from the 1800s to World War II, Asphalt Institute, accessed 10/04/2021, http://asphaltmagazine.com/asphalthistory_two/#:~:text=The%20first%20sheet%20asphalt%20pavement,the%20remainder%20of%20the%20pavement.

[8] Jane Hutton. Reciprocal Landscapes, Stories of Material Movements. Routledge, 2019, 16-17

[9] Basil A. Reid. Archaeology and geoinformatics : case studies from the Caribbean. University Alabama Press, 2008, 33-73

[10] Ibid.

[11] Gertrude Carmichael. The history of the West Indian islands of Trinidad and Tobago, 1498-1900. Columbus Publishers, 1961.

[12]Reid. Archaeology and geoinformatics, 33-73

[13] Vernon C. Mulchansingh. The Oil Industry in the Economy of Trinidad. Institute of Caribbean Studies, 1971, 73

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] John Dryden., “Pas de Six Ans!” In: Seven Slaves & Slavery: Trinidad and Tobago 1777–1838, by Anthony de Verteuil, Port of Spain, 1992, 371–379.

[17] Trinidad and Tobago, Encyclopedia.com, 2018, accessed 11/04/2021. https://www.encyclopedia.com/places/latin-america-and-caribbean/caribbean-political-geography/trinidad-and-tobago#HISTORY

[18] Drysdale, W. “Trinidad’s Lake of Pitch” In: The American Architect and Building News (1876-1908). American Periodicals Series III, 1886, 201

[19]Tim Daley. La Brea Pitch Lake: The Largest Tar Pit in the World. GeoExPro, 2019, accessed 11/04/2021. https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2019/10/la-brea-pitch-lake-the-largest-tar-pit-in-the-world

[20]Davis. The asphalt industry from the 1800s to World War II

[21] Bezier. The world in a grain. 53

Bibliography

Beiser, Vince. The world in a grain : the story of sand and how it transformed civilization. Riverhead Books, 2018

Bitumen Applications, Nuroil Trading, 2014, accessed 10/04/2021, https://www.nuroil.com/bitumen-applications.aspx

Carmichael, Gertrude. The history of the West Indian islands of Trinidad and Tobago, 1498-1900. Columbus Publishers, 1961.

Daintith, Terence. Finders Keepers? How the Law of Capture Shaped the World Oil Industry. Routledge, 2010

Daley, Tim. La Brea Pitch Lake: The Largest Tar Pit in the World. GeoExPro, 2019, accessed 11/04/2021. https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2019/10/la-brea-pitch-lake-the-largest-tar-pit-in-the-world

Davis, John. The asphalt industry from the 1800s to World War II, Asphalt Institute, accessed 10/04/2021, http://asphaltmagazine.com/asphalthistory_two/#:~:text=The%20first%20sheet%20asphalt%20pavement,the%20remainder%20of%20the%20pavement.

Dryden, John. 1992, “Pas de Six Ans!” In: Seven Slaves & Slavery: Trinidad and Tobago 1777–1838, by Anthony de Verteuil, Port of Spain, 1992

Drysdale, W. “Trinidad’s Lake of Pitch” In: The American Architect and Building News (1876-1908). American Periodicals Series III, 1886

Hutton, Jane. Reciprocal Landscapes, Stories of Material Movements. Routledge, 2019

McIntosh, Jane. The Ancient Indus Valley. ABC-CLIO, 2007

Mulchansingh, Vernon C. The Oil Industry in the Economy of Trinidad. Institute of Caribbean Studies, 1971

Nag, Oishimaya Sen. The unique pitch lakes of the world. WorldAtlas, 2021, accessed 09/04/2021, https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-five-natural-asphalt-lake-areas-in-the-world.html

Reid, Basil A., Archaeology and geoinformatics : case studies from the Caribbean. University Alabama Press, 2008

Trinidad and Tobago, Encyclopedia.com, 2018, accessed 11/04/2021. https://www.encyclopedia.com/places/latin-america-and-caribbean/caribbean-political-geography/trinidad-and-tobago#HISTORY

What are Diatoms?. Diatoms of North America, accessed 09/04/2021, https://diatoms.org/what-are-diatoms