The weaponizing of architecture in Canada’s longest running residential school.

In a report written to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, providing advice on how to assimilate the native population to the culture of the colonisers, it was observed from the American government’s experience that when children are permitted to return home after school, “the influence of the wigwam was stronger than the influence of the school” [1]. The power of spatial organisation and occupation of architectural spaces on the culture of a community was recognised early on, and architecture became one of the prominent tools of violence employed against native populations in colonised regions, in the form of residential schools.

Operated by the federal government in participation with various church denominations, the ambition of residential schools in Canada was to ‘remove and isolate [Indigenous] children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture’ [2]. This was done by establishing boarding schools, spatially separated from the children’s home communities, where the colonisers prevented the practice of native languages and cultures as well as restricted contact with family members. Techniques of violence and abuse were employed to achieve these ends, as well as in instances that were not directly related to the oppression of native culture and could only be described as instances of entertainment for the colonisers. As institutions of violence and oppression, the architecture of the school’s themselves played a vital role in establishing and expanding the relationship of oppression between the colonisers and local native populations.

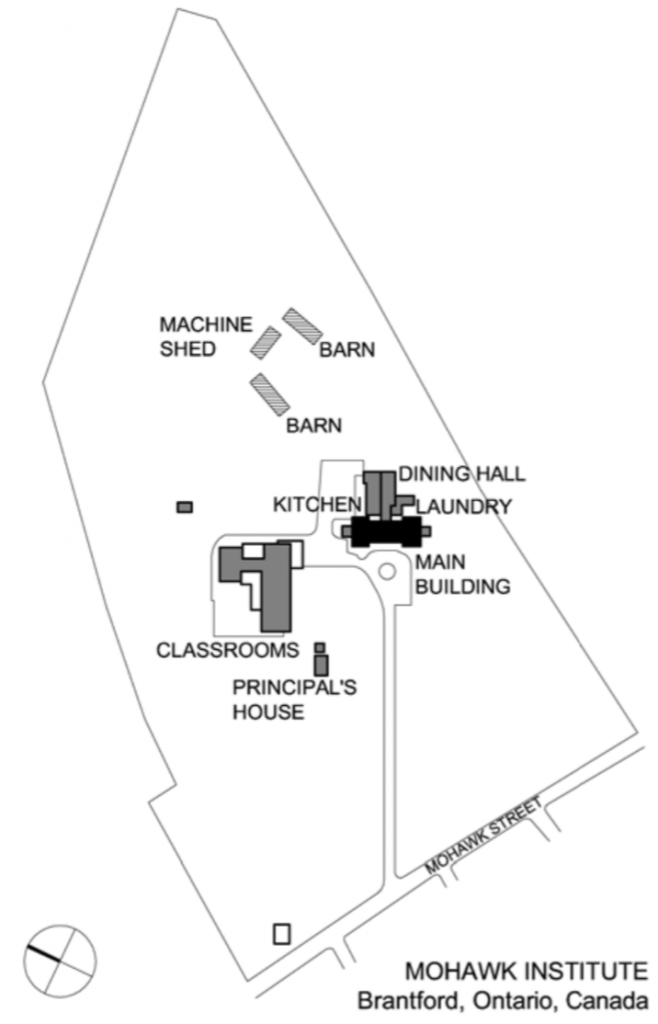

Established in 1829 by the New England Company, a Protestant missionary organization, the Mohawk Institute was the earliest and longest running residential school in Canada [3]. Located in Mohawk Village near the settler town of Brantford, Ontario, the institute was constructed on land granted by Six Nations and the colonial government.

The predecessor to the Mohawk Institute was a day school established in the 1780’s by the leader of the Mohawks, Thayendenegea, who based the design of the day school on his own experience of a European-style education in Connecticut [4]. Here, students practiced a cultural exchange by learning English while teaching the Mohawk language and culture to others. The intention of this day school was to train both settler and indigenous students as missionaries, diplomats, and translators, preparing members of both communities alike to join society as a functioning, contributing member.

The prominent goal of the Mohawk Institute at its inception was to oppress indigenous culture and force assimilation, which was achieved through unbearable and ever-present forms of violence, such as the act of pushing pins through the tongue of a student who spoke their native language. At the same time, the spirit of its predecessor of providing students with skills to integrate within and contribute to the settler society formed the foundation of its curriculum. The Mohawk Institute was initially established as a mechanic’s institute for male students from the nearby Six Nations [5]. The building included a mechanic’s shop, with curriculum including carpentry and tailoring. When female students were introduced, the curriculum was separated by gender with male students being trained in trades and farming and female students in housekeeping. While the curriculum included academics, the emphasis was on vocational and industrial training, in anticipation of the student’s eventual participation in the settler economy [6]. The vocational exercises were often profitable to the school, including sewing of school uniforms, cleaning, and construction and repair of school buildings, forcing students to actively take part in constructing the weapon to which they were subjected. Adopting the typology of industrial school, residential schools became an intermediate setting between academic schools and reformatories [7].

The first significant change to the architectural form of the school was the addition of residences for ten boy and ten girls in 1833, introducing what would become the devastating spatial dislocation of indigenous students from their home communities that proliferated in residential schools. In 1860, a large farm was acquired by the school [8]. Students were trained in farming on this site, and later involved in outing programs where they were sent to settler communities for work, often as farmhands. This arrangement furthered the theme of spatial dislocation, dissolving the sense of spatial belonging that the students once had within their communities and native regions.

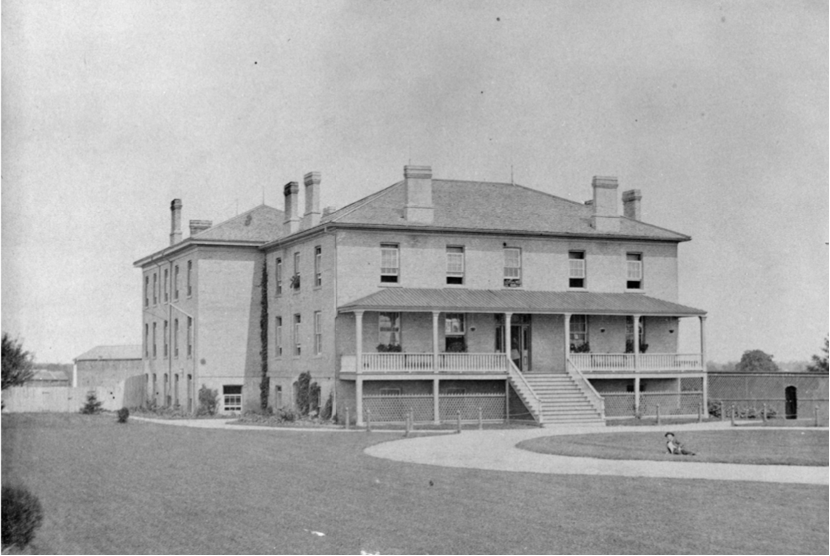

Acts of rebellion by the students were common, including desertion and property destruction, with arson being the most effective way for students to protest as it directly and efficiently destroyed the physical structure that upheld the institution. The Mohawk Institute was first destroyed by fire in 1854 [9]. The government had since intervened in the planning of the region, moving the Six Nations to part of their land to the south in 1841 and abandoning Mohawk Village, as such the institution was rebuilt on a new 10-acre lot purchased by the New England Company. The design of the new school building adopted simple European forms in its external expression, composed of a symmetrical two-story box of white brick with Georgian elements [10]. This included symmetrical chimneys, a hipped roof, and a row of five unpaired windows on the second level. A verandah spanning the width of the front elevation with a large, centered staircase contributed to the imposing yet domestic character of the building.

As the architecture of the site changed, so did the internal curriculum. Direct vocational training such as carpentry and blacksmithing were discontinued in favor of agricultural programs, with the institution subsidizing students to start farms near the site upon graduation instead of returning to their home communities. While these pursuits were of value to the students, they were more so a significantly profitable exercise for the institution.

Throughout the years and despite stagnant enrolment rates, the physical presence of the school building continued to grow, both in terms of scale and architectural expression. Additions that were visible to the public significantly widened the building and introduced Victorian Gothic detailing including a turret, dormers with finials, and gable trim [11]. At the same time, dormitories were constructed and expanded in ways that they remained hidden and separated from the public.

With a change in agenda, now focussing increasingly on forced assimilation, students from as far away as Quebec began to attend the Mohawk Institute in 1885 [12]. The detrimental effects of spatial dislocation on indigenous culture were capitalized on by creating large distances between students and their home communities. In 1891, as residential schools began to receive per-capita funding from the federal government, overcrowding began to occur, further degrading the experience of residents within these sites.

Protests in the form of arson again occurred in 1903, with students successfully destroying the school building [13]. The site was then rebuilt in 1904, this time set back from the street at the end of a long drive, furthering its separation from the surrounding community. The school was rebuilt in imposing red brick, abandoning the domestic qualities of the previous site and adopting a heavier massing [14]. The new building projected an image of authority and solidity, built in a neoclassical style that included a central verandah with two-story Doric columns and a domed cupola, in an attempt to give credibility to the abuses that occurred within the site.

The manner in which the indigenous population was addressed by the settler society had at this point dramatically departed from that of the Mohawk Institute’s predecessor, in which cultural collaboration was prioritized. Moving towards a segregationist strategy in the second generation of residential schools, the typology of industrial school was abandoned, and a more economical approach of boarding schools was adopted [15]. Commentary from the superintendent of Indian Affairs at this time declared that it was an undesirable use of public money to educate the indigenous population to complete industrially with the settler community. As such, the focus of the Mohawk Institute and other residential schools in this era shifted away from education and towards the indoctrination and assimilation of indigenous youths through abusive and violent methods.

The Mohawk Institute continued to expand, with the curriculum focused on assimilation and complete erasure of indigenous culture, until the school’s closure in 1970 [16]. Renamed the Woodland Cultural Centre in 1972, the site has since been reclaimed and operated by Indigenous communities as an educational centre, documenting and sharing the violent history of the Mohawk Institute and wider residential school system to the present-day community.

Repatriation of the physical built site to the Indigenous community is a fledgling step towards reconciliation, and much remains to be done given the insurmountable amount of abuse that occurred within the residential school system. This cannot begin to be addressed without acknowledging the multifaceted tools of violence that were employed within this system, including the means in which architecture was weaponised. The settler’s imagined association between a civilized society and the built environment gradually shifted their agenda from cultural collaboration to assimilation by distancing indigenous youth from their homes, thought of as the wigwam, and placing them in a rigid, European settler style structure, the residential school [17]. Changes in institutional priorities, moving towards increased assimilation and erasure, were reflected in the architectural rebuilding and renovating of the site, moving towards a heavier massed, increasingly secluded institution. The relationship between the evolving architecture of residential schools and the worsening agenda of the settler society is evident and is one of many important topics to study and recognise in order to begin to fully comprehend the depth and magnitude of abuse that occurred within the Canadian residential school system.

Bibliography

Groat, Cody. “Commemoration and reconciliation: the Mohawk Institute as a World Heritage Site.” British Journal of Canadian Studies 31, no. 2 (2018): 195-209.

Milosz, Magdalena. “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools.” M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015.

Milosz, Magdalena. “Residential School Architectures in Canada, USA, Australia, and New Zealand.” Society of Architectural Historians Australia & New Zealand Annual Conference Proceedings (2017). 443-458.

The Anglican Church of Canada. “The Mohawk Institute – Brantford, Ontario.” Last modified September 23, 2008. https://www.anglican.ca/tr/histories/mohawk-institute/.

Woodland Cultural Centre. “About the Centre”. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.anglican.ca/tr/histories/mohawk-institute/.

Engracia De Jesus Matias Archives and Special Collections. “Photographs of students working in the garden.” Photograph taken 1943 at the Mohawk Institute, reproduced in 1991. http://archives.algomau.ca/main/?q=node/15593.

Notes

[1] Magdalena Milosz, “Residential School Architectures in Canada, USA, Australia, and New Zealand,”Society of Architectural Historians Australia & New Zealand Annual Conference Proceedings (2017): 444.

[2] Cody Groat, “Commemoration and reconciliation: the Mohawk Institute as a World Heritage Site,” British Journal of Canadian Studies 31, no. 2 (2018): 195.

[3] Magdalena Milosz, “Residential School Architectures in Canada, USA, Australia, and New Zealand,”Society of Architectural Historians Australia & New Zealand Annual Conference Proceedings (2017): 448.

[4] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 35.

[5] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 35.

[6] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 39.

[7] Cody Groat, “Commemoration and reconciliation: the Mohawk Institute as a World Heritage Site,” British Journal of Canadian Studies 31, no. 2 (2018): 200.

[8] Magdalena Milosz, “Residential School Architectures in Canada, USA, Australia, and New Zealand,”Society of Architectural Historians Australia & New Zealand Annual Conference Proceedings (2017): 448.

[9] Magdalena Milosz, “Residential School Architectures in Canada, USA, Australia, and New Zealand,”Society of Architectural Historians Australia & New Zealand Annual Conference Proceedings (2017): 448.

[10] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 43.

[11] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 46.

[12] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 49.

[13] Magdalena Milosz, “Residential School Architectures in Canada, USA, Australia, and New Zealand,”Society of Architectural Historians Australia & New Zealand Annual Conference Proceedings (2017): 49.

[14] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 53.

[15] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 43.

[16] Cody Groat, “Commemoration and reconciliation: the Mohawk Institute as a World Heritage Site,” British Journal of Canadian Studies 31, no. 2 (2018): 196.

[17] Magdalena Milosz, “Don’t Let Fear Take Over: The Space and Memory of Indian Residential Schools” (M.Arch. diss., University of Waterloo, 2015), 48.