Colonial hotels are a deep-rooted architectural typology among the urban landscape to emerge from the colonial British administration era. Hotels provided not just higher standards of comfort and living through the buildings’ size, facilities, and standards of services compared to other travelers accommodations available, but they also provided a space for the localization of modernity in the colonial setting. The Raffles Hotel exhibits the complexities entangled with marketing tourism through the Raffles brand and the romanticization of Singapore’s colonial histories. Neglecting the ramification of the Raffles Town Plan or Jackson Plan and its outcome on the landscape. Distinguishing a balance between conservation and commercial intentions regarding the colonial heritage that is attached to a place; further shedding light on the dilemmas regarding the various ways in which the conserved past should be presented as a contemporary tourist destination.

The Raffles Hotel is a colonial-style luxury hotel located in the downtown core district of the city of Singapore. Established by the Sarkies Brother in 1887, the hotel was formally named after British statesman Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles; founder of colonial Singapore. Who transformed the city into a trading port for the British East India Company.

Originally a privately owned beach house built in the early 1830s, the property was then leased by Dr. Charles Emerson in 1878 and later converted into a seaside hotel. Upon his death in 1883, the hotel closed. Subsequently, after the expiration of Dr. Emerson’s lease, the Sarkies Brothers who were owners of the successful Eastern & Oriental Hotel in Penang leased the property with the objective of transforming the beachside hotel into a high-end luxury hotel in Singapore. On December 1st, 1887 the Raffles Hotel officially opened, named after Singapore’s colonial founder, Sir Stamford Raffles 1.

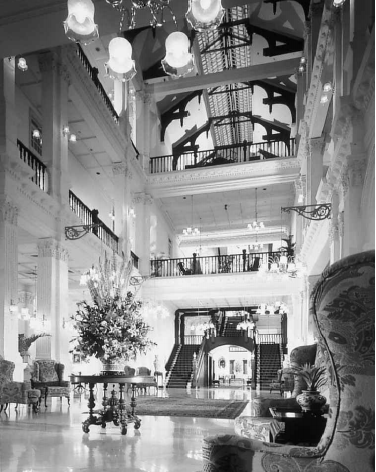

The hotel’s proximity to the beach and its high standards of service and accommodation generated a well-liked reputation among wealthy clientele. Within the first decade of the opening, the hotel rose in popularity through the addition of new architectural features such as verandas, a ballroom, and a billiard in order to meet the demands for more accommodations. The main building of the Raffles Hotel was designed by Regent Alfred John Bidwell2. The state-of-the-art building used an amalgamation of European colonial architecture combined with traditional local elements. Integrating tropical architectural features such as high ceilings and large verandas to suit the environment the building resides in along with the inclusion of modern technology such as powered ceiling fans and electric lights. The utilization and promotion of Western technology and consumer products provided a primary means of modernity within the urban fabric of hotels. The Raffles Hotels advertised the luxury and modernity within the hotel through the printed advertisement of the grand opening of the hotel in 1899 proclaiming “The Electric Lights will be used for the first time and the comfort of guests will be imminently improved by the Electric Fans”3.

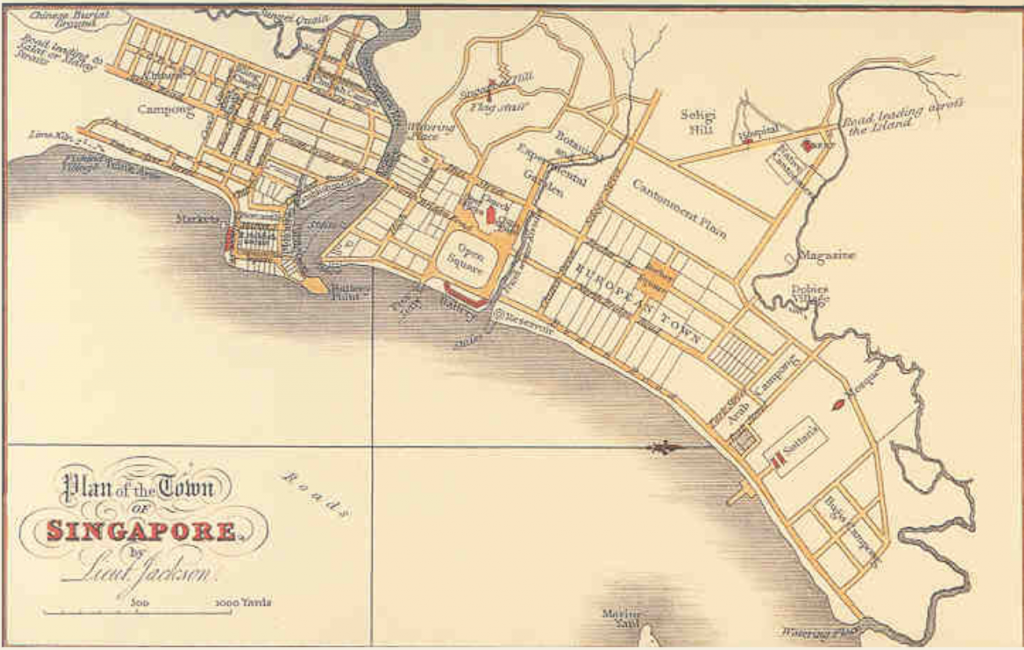

The popularization of luxurious hotels aided in the rapid growth of tourism and economic activities in Singapore. The Raffles Hotel illustrated an excellent example of the difficulties of creating a balance between heritage tourism and the efforts of reconciliation of conservation and commerce at historic sites4. Restoration of the hotel maintains to promote features and experiences of the hotel as a representation of Singapore, allowing tourism revenue to maintain the property. However, restoration of the building creates the dilemma of distorting history as “It is difficult to know where one is in the Raffles Hotel which exists prior to restoration and what is a relocation of the original”5. By advertising Raffles as a brand of luxury and recalling the hotel’s status to obscure the colonial heritage and create an oriental fantasy. Rather than shedding a light on the ramification of Raffles’ Jackson plan on indigenous sites of land and the segregation of indigenous ethic groups created by the reengagement of land for commercial benefits. Designed in accordance with Lieutenant-governor Sir Tomas Stamford Raffles, the Jackson Plan implemented a grid system to maintain order among the urban fabric to create the idealized scheme of how the city of Singapore should be rearranged6. The urban plan segregated the population according to ethnicity, separated into four areas to be able to exercise control over the local population. Resulting in reserved property for European settlers, economically beneficial establishments, and trade7. Through the changes in the physical appearance, architecture and urban fabric, the city of Singapore transformed from a fishing village of about 150 people to one of the busiest global ports8.

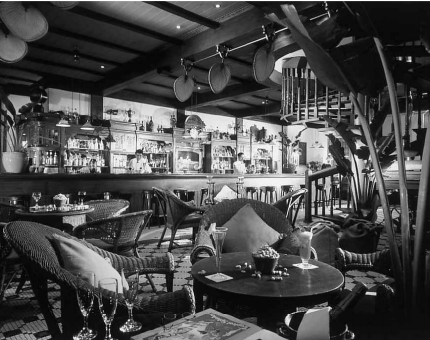

The construction of the Raffles luxury hotel further masks the colonial past and its impacts and exploitation of culture and heritage on the indigenous land. The manner in which the city’s colonial past along with the indigenous land is exploited in the hotel’s advertising strategies portrays the hotel through a lens of romanization and nostalgia for the colonial era. This provides a partial view of history and promotes the colonizer’s history and Western cultures while providing little attention to the local Asian culture, perspective, and heritage9.

The branding strategies invoked through the Raffles Hotel solicits not only a luxury western lifestyle but also a sense of nostalgia for the colonial past. The Raffles brand aims to maintain its prestigious reputation as among the finest hotels internationally through the rationale of romance. The allure of romance and the luxurious lifestyle associated with the Raffles Hotel emerges from the narrative of an Oriental fantasy of seeking the “Western” life where the “East” and West” converge through architectural space10. Along with a list of eminent guests internationally, who have in turn become characters among the romance that the Hotel advertises. Using the powerful imagery of William Somerset Maugham’s reference of “standing for all the fables of the exotic East”11. To further reinforce the association of the Raffles Hotel with both Western living in the exotic East.

Singapore’s colonial built heritage such as the Raffles Hotel has been preserved through conservation efforts by primary means of tourism and economic motivations. The Raffles hotel utilizes the power of the imagery of a luxury experience through the Raffles brand, promising more than just a lifestyle. The Raffles brand provides individuals with a unique experience through various methods of exclusivity, intimacy, romance, and allure of the city’s colonial past. However, the Raffles experience should not just be associated with the consumption of luxury. I believe the usage of the brand title should bring forth more attention to the colonial histories of the land and the impacts it held on indigenous ethics groups rather than the symbolic social entities of consumption.

Footnotes:

(1) Cangi, Ellen C. (1 April 1993). “Civilizing the people of Southeast Asia: Sir Stamford Raffles’ town plan for Singapore, 1819–23”. Planning Perspectives: 166–187.

(2) Raffles Singapore, “History of Singapore Hotel: Raffles Hotel Singapore,” Historic Hotels Worldwide, accessed April 27, 2021, https://www.historichotels.org/hotels-resorts/raffles-hotel-singapore/history.php.

(3) Peleggi, Maurizio. “The social and material life of colonial hotels: Comfort zones as contact zones in British Colombo and Singapore, ca. 1870–1930.” Journal of Social History 46, no. 1 (2012): 124-153.

(4) Henderson, Joan C. “Conserving colonial heritage: Raffles hotel in Singapore.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 7, no. 1 (2001): 7-24.

(5) Henderson, Joan C. “Conserving colonial heritage: Raffles hotel in Singapore.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 7, no. 1 (2001): 22.

(6) Teo Siew Eng. “Planning Principles in Pre- and Post-Independence Singapore,” The Town Planning Review 63, no.2 (1992): 166.

(7) Teo, Peggy, and Shirlena Huang. “Tourism and heritage conservation in Singapore.” Annals of Tourism Research 22, no. 3 (1995): 589-615.

(8) Henderson, Joan C. “Conserving colonial heritage: Raffles hotel in Singapore.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 7, no. 1 (2001): 7-24.

(9) J.E. Tunbridge, `Whose heritage to conserve? Cross-cultural reflections on political dominance and urban heritage conservation, Canadian Geographer, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1984, pp. 171-180.

(10) Aljunied, Syed Muhd Khairudin, and Derek Heng. Reframing Singapore: Memory-Identity-Trans-Regionalism. Amsterdam University Press, (2009): 249

(11) Aljunied, Syed Muhd Khairudin, and Derek Heng. Reframing Singapore: Memory-Identity-Trans-Regionalism. Amsterdam University Press, (2009): 249

Bibliography:

Aljunied, Syed Muhd Khairudin, and Derek Heng. Reframing Singapore: Memory-Identity-Trans-Regionalism. Amsterdam University Press, 2009.

Cangi, Ellen C. “Civilizing the people of Southeast Asia: Sir Stamford Raffles’ town plan for Singapore, 1819–23.” Planning Perspective 8, no. 2 (1993): 166-187.

Eng, Teo Siew. “Planning principles in pre-and post-independence Singapore.” The Town Planning Review (1992): 163-185.

Henderson, Joan C. “Conserving Colonial Heritage: Raffles Hotel in Singapore.” International Journal of Heritage Studies : IJHS 7, no. 1 (2001): 7-24

“History of Singapore Hotel: Raffles Hotel Singapore,” Historic Hotels Worldwide, accessed April 27, 2021, https://www.historichotels.org/hotels-resorts/raffles-hotel-singapore/history.php.

Peleggi, Maurizio. “The social and material life of colonial hotels: Comfort zones as contact zones in British Colombo and Singapore, ca. 1870–1930.” Journal of Social History 46, no. 1 (2012): 124-153.

Philip Jackson, Plan of the Town of Singapore by Lieut. Jackson, 1823, Urban Planning Document, National Museum of Singapore: Singapore History Gallery, Singapore.

Teo, Peggy, and Shirlena Huang. “Tourism and heritage conservation in Singapore.” Annals of Tourism Research 22, no. 3 (1995): 589-615.

Tunbridge, John E. “Whose heritage to conserve? Cross-cultural reflections on political dominance and urban heritage conservation.” Canadian Geographer 28, no. 2 (1984): 170-180.