One of the defining characteristics of 19th century social and cultural thought was a shift in man’s approach towards science and reinterpretation of the relationship between human creation and divine inspiration. The architectural debates that dominated this moment of history are expressed in the Oxford museum’s 1854 competition to create the two-storey natural history museum building. The only requirements of this competition were that the proposed building would need to have “three sides of a quadrangle, with an open side allowing for further expansion (and that) the courtyard was to be covered by glass and iron roof” (Blau 1982, 66). Many of the chief architectural voices in this competition including Henry Acland viewed the natural history museum as a vehicle to exhibit God’s works. After receiving the architectural propositions in October of the same year, the committee of delegates overseeing the competition chose Deane and Woodward’s design, not without difficulties. Then the real work started; Deane and Woodward had to redraw the plans multiple times to satisfy every science department. The construction went on for 20 years. The interior decoration and layout were still changing even after the official ending of the construction site.

This article argues that the Oxford Museum of Natural History is fundamentally a religious monument. The debates over style and tensions about technology that characterized this chapter of history are captured in the construction decisions of the museum, and the structural choice made regarding gothic style over classicism; The construction of the Oxford Museum demonstrates the desire to answer new questions about the relationship between humanity, science, and God that bubbled into the minds of thinkers during the Victorian era.

The Oxford Museum’s arguments as a religious monument are found in the traditional analysis elements of museums. As a matter of fact, a museum is its collection. Through the history, the primary collection and the museum itself, they got a greater understanding of God. A museum is also its experience. By choosing neo-gothic architecture and innovating within this style culture, they merged tradition and technology.

A museum is its collection.

Over the last century, bourgeois in Britain, the epicentre of empire, one of the heads of colonialism, developed a passion for collecting. They collect natural objects and human-made objects. It’s a strong relationship between God-made, the objects, and human-made, the collection. Before the scientific classification – taxidermy – entering a collection room was very confusing. There was no objective relationship between the objects. It was the collector’s creation; he had to share with his visitor the links that allowed all those items to live in the same room. He and his idea of his collection were the only links between those objects. From this way of collecting human objects, biological specimens and natural data, they obtained really eclectic collections. It was the beginning of sciences as we might recognize today and museums.

“They invented rooms with defined boundaries for scholarship and with the distinct purpose of virtual scrutiny; these spaces led to the wide range of purpose-built museum in the nineteenth century” (Yanni. 1999. 23)

In 1833, the word science was publicly used and accepted in England for the first time. Around this moment, they started to experiment more and to implement the theory of Darwin. They begin to understand the relationship between species and develop the taxidermy, which is the naming and classing of species’ science. It’s a powerful science because they have the right to hierarchies’ God’s specimens always with humans on top of every species.

The museum’s primary collection allows the museum to exist even today; if the collection disappears, the museum dies. Oxford Museum’s first collections were geological (gems and rocks) from Clarendon Hall, anatomical from Christ Church College and general natural historical specimens from Ashmolean Museum. The last acquisition created a relation between Oxford and Ashmolean Museum. This relation began with Ashmolean Museum splitting their collection and keeping their Archaeological collection. When they gave their natural collection, it allowed Ashmolean to grow the other main collection – the archeological one – with objects from all around the world – a topic for another time.

“The museum buildings offer proof of the Victorians’ grand belief in the expressiveness of architecture. And today the displays are historical evidence of our relationship to the natural world.” (Yanni. 1999. 13)

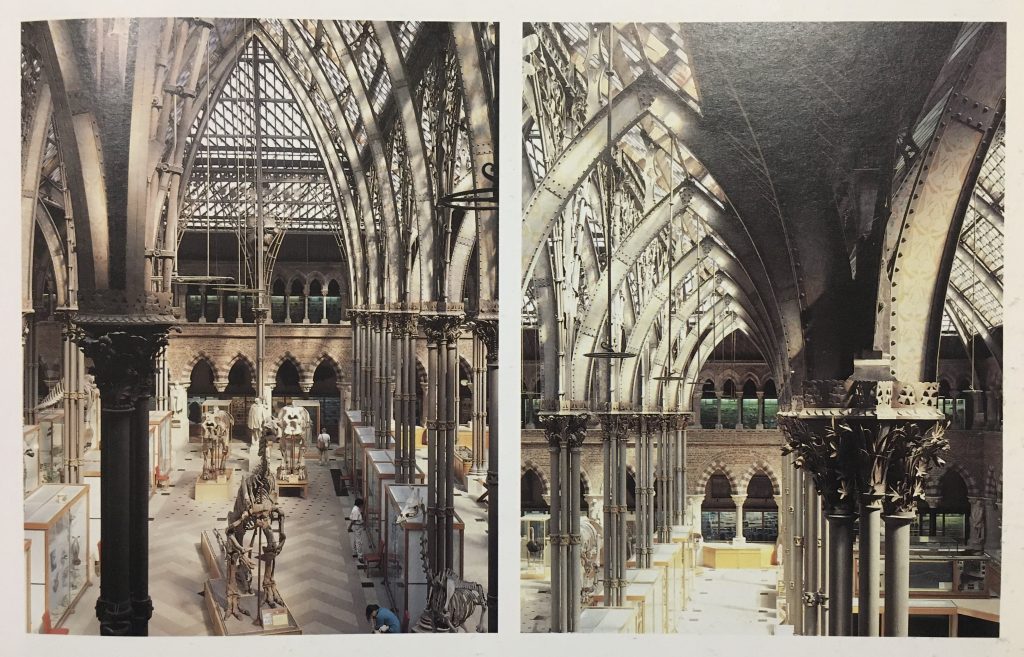

Each century has its approach toward science, its vision. Those visions influence art and architecture. And during the Victorian era, people still believed in God’s beauty and tried to justify it by creating and building art pieces representing its work. By choosing a gothic highly decorated interior building to display their collection, the Oxford board also determines an integral part of the museum and the relationship to a loaded national religious past. But “Museums die only if their collections are dispersed, but buildings may be changed and altered at will” (Forgan. 2005) so the building is a changing part of the museum that can be altered and modified in time, but the collection must remain for it the survive. In this museum, the collection is exposed under an innovative glass and iron roof. The light coming from it give a zenithal ambiance and enlightens all the iron art details.

A museum is its experience

First, the studies of the building’s physical materiality reveal some possibilities of tradition over technology, but when the research is pushed, it’s not the case anymore. Both are represented in their own way through the construction of the museum. Tradition and technology are both expressed through the space experience of the Oxford Museum. By choosing neo-gothic architecture and innovating within this style culture, they allowed the museum to became a Victorian Monument. When we look at the museum from the exterior, it is quite a traditional gothic building. The stone facing is prominent with beautiful carving art around the door and windows.

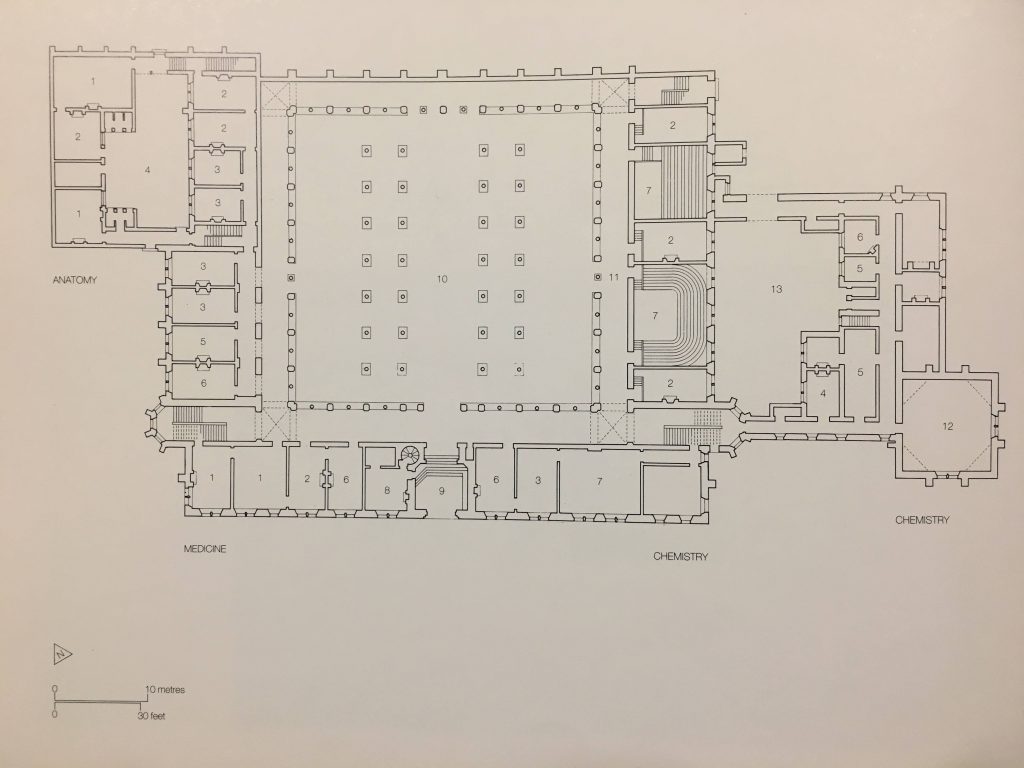

The organization of the plan placed the courtyard/exposition as a central and convergence space. Since Oxford Museum is more than just a museum, all the offices, laboratories and lecture rooms of the new science departments for Oxford University are there, around the exposition, looking over it. The plan is not entirely new; there are traditional’s meaning and process behind it:

“The fact that the interior resembles a cloister shows a link between science and religion – the professor’s offices around the edges are like cells and the interior of the court, where a garden would grow in a monastery, is filled with natural specimens.” (Yanni, 1999, 80)

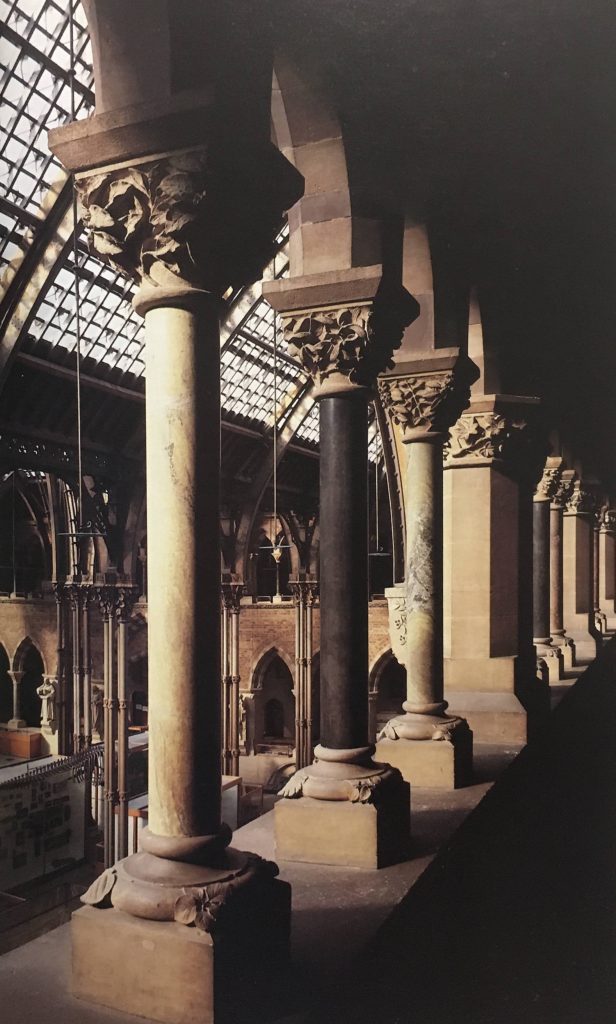

Ruskin was the interior detailer on the project; he was also subtly implicated in the project’s choice during the competition since he is a good friend of Acland. He didn’t draw the museum’s interior details, but in the original proposition, the detail of Woodward and Deane were inspired by his essay about gothic revival. There are three guiding principles but the second is to most relevant to our topic: “… all art employed in decoration should be informative, conveying truthful statements about natural facts… with as much resemblance to nature as the necessary treatment of the piece of ornament in question will admit of.” (Blau. 1982. 76)

Woodward’s care in choosing the design in the iron capitals is a way to communicate the complexity and variety of nature. Also, they were able to acquire a fair amount of detail due to “The O’Shea brothers, the craftsmen who travelled from Dublin to Oxford to carve these naturalistic decorations in stone, created an ornamental program of surprising variety, displaying a knowledge of medieval precedent as well as unusual skill.” (Yanni. 1999. 81)

They represented the complexity of the collection in many details (figure 5); it is a tribute to god work by a man’s hand.

Beauty in the complexity

In conclusion, the Oxford Museum of Natural History is a religious monument, The debates over style and tensions about technology of the victorian era are captured in the construction decisions involved in the making of the museum, and the structural choice made regarding gothic style over classicism in the construction of the Oxford Museum demonstrates the yearning to answer new questions about the relationship between humanity, science, and God that vexed the minds of thinkers during the victorian era. In all the process of choosing, building and living the Oxford Museum of Natural History live and evolve with the burden of dichotomy: classical vs gothic, sciences vs religion, art vs technology, creation vs evolution, etc. As a way of reassurance for this imposing and extraordinary Victorian Monument “Ruskin himself wrote, ‘truths may be and often are opposite though they cannot be contradictory.'” (Yanni. 1999. 90) The beauty in the complexities of museum architecture is the better understanding of the constant changes in our relationship with science; and the economic, cultural and intellectual influence in the creation of spaces.

Bibliography

1 – Blau, Eve. 1982. Ruskinian Gothic. Guildford (Surrey): Princeton University Press.

2 – Yanni. 1999. Natures Museums. London: The Athlone press.

3 – Forgan, Sophie. “Building the Museum: Knowledge, Conflict, and the Power of Place.” Isis 96, no. 4 (December 1, 2005): 572–85. https://doi.org/10.1086/498594.

4 – Yanni, Carla. “Divine Display or Secular Science: Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 3 (September 1, 1996): 276–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/991149.

5 – Galison, Peter, and Emily Ann Thompson. 1999. The Architecture Of Science. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

6 – Dobraszczyk, Paul, and Peter Sealy. 2016. Function And Fantasy. Brookfield: Taylor and Francis.

7 – Nichols, Kate. 2015. Greece And Rome At The Crystal Palace. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

8 – Vernon, Horace Middleton, and K. Dorothea Ewart. A History of the Oxford Museum. Oxford,: Clarendon Press, n.d. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/259513.

9 – Lofthouse, Richard A. 2015. European Intellectual History From Rousseau To Nietzsche. Yale University Press.

Figures

1 – Garnham, Trevor, and Martin Charles. 2010. Oxford Museum. London: Phaidon.

2 – Blau, Eve. 1982. Ruskinian Gothic. Guildford (Surrey): Princeton University Press.