An investigation into the Flatiron Building as an Icon of capitalism.

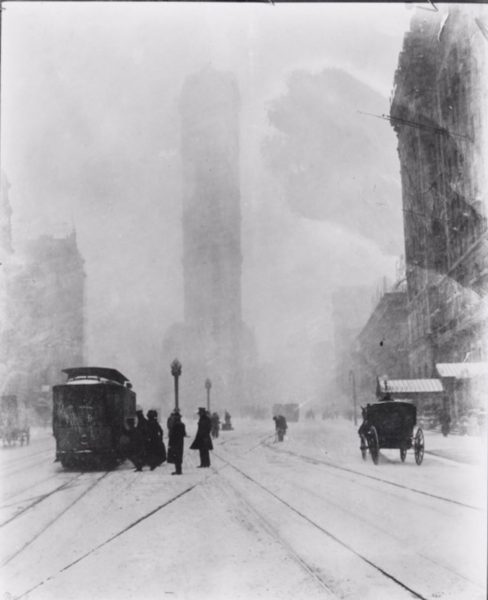

Unknown. 1902. Flatiron Building, N.Y..

As America grew in the late 1800s a new form of empire was emerging. The United States had vast amounts of resources, people and products. New York city was the capital of an economic empire. As capital accumulated in New York city it manifested in the built environment as monumental buildings. These buildings grew in step with the economy making New York the cluster of tall buildings we know today. I will investigate one of these buildings, the Flatiron, as a case study of how the capitalist and empirical attitudes in America were reflected in the buildings they created. This essay will explore how the Flatiron became a prototype for skyscrapers as icons for consumptive capitalism. I will also argue that the Flatiron legitimized capitalistic ideals simply by being built in the public eye. I seek to illustrate that the Flatiron was a consequence of the brand of capitalism that thrived in North America for so long, and also how skyscrapers may come to serve as a warning for future generations about the perils of greed and overconsumption.

Objects that transcend their original identity have the ability to become icons. The meaning that people associate with these objects allows those objects (and their reproductions) to communicate and reinforce ideas across time. Consider the difference between a mannequin and a statue in the middle of a town square. One is merely a form and the other communicates a meaning. In this sense the Flatiron building is an icon amongst other skyscrapers. The building is not particularly special in terms of size or ornamentation, but the timing, technology and cultural impact of the project elevated its status to that of an architectural icon. In doing so it legitimized the capitalist frenzy that defines much of North America.

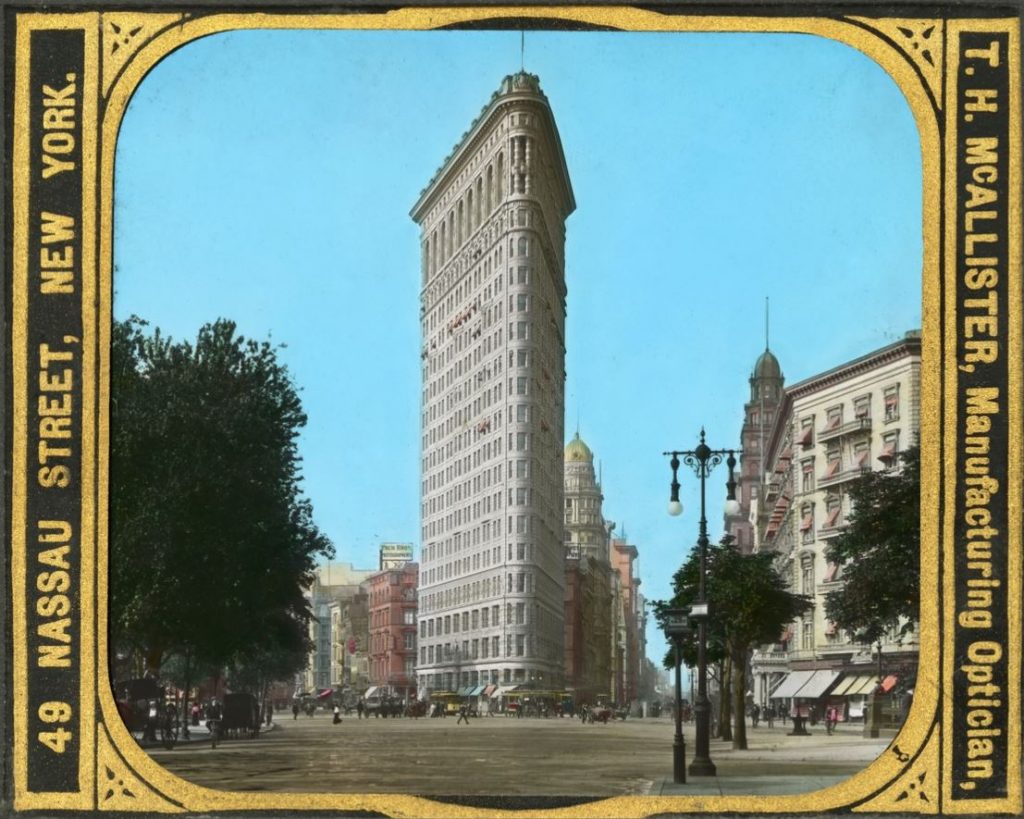

The Flatiron was completed in 1902 and is situated in the geographic heart of New York City at the point of 23rd street intersecting with Broadway. The project was commissioned by the Fuller construction company and was designed by Daniel Burnham, an early adopter and pioneer of the steel frame skyscraper typology. The site is triangular and Burnham built the Flatiron with three facades to suit this unusual condition. This resulted in the unique tower that would be known as the Flatiron. The unusual look prompted many to talk about it, photograph it and give their opinions on it. I believe that this frenzy of attention was the beginning of it becoming known as an icon. The Flatiron building stands twenty stories high. It’s 3 sides are decorated in the typical ornate Beaux-Arts fashion of the early 20th century. It is widely accepted as one of the most important skyscrapers in history 1..

The Flatiron was able to be built because of a convergence of harmonious economic and social circumstances in the late 1800’s. It was a prosperous time for New York and spaces to operate businesses were in high demand. At the time that the Flatiron was built more than two thirds of the top 100 American corporations were headquartered in New York City2.. This created a huge demand for office space, and on an island like Manhattan that can only be built out to the extents of its shores, building skyward becomes a commercially attractive endeavour. Furthermore the city building codes were changing to allow buildings to be much taller. This was made possible by the advent of structural steel as a mass produced building material. The great Chicago fire of 18713. had left city dwellers weary of timber structures which meant that steel beam buildings were soon to be the primary typology of tall buildings in major cities in North America.

But is it appropriate to label a building as an “icon”? It is certainly a loaded term, usually reserved for religious statues of historical monuments. The Flatiron became a new type of icon, not attached to religion or an individual or a momentous occasion but instead to capitalism and the accumulation of vast amounts of material wealth. Gone are the days of religious architecture being what drives the craft now it is mostly economic and commercial drivers that propel architecture. The architect Charles Jenks put it succinctly in this passage from his essay on iconic buildings: “If an iconic building must have a new and provocative image, and also cannot directly call on the iconography that underlay traditional or religious architecture (because that is no longer believed), then it must produce enigmatic signifiers that allude to unusual codes. These will be affective, and some of the excitement will come from the convulsive interaction of the meanings4..” In the case of the Flatiron the meanings were strictly commercial.

Traditional icons were not inhabited by people. You observed them, you did not enter them. The new icon of the skyscraper consumed people, and demanded a monthly sacrifice to stay within. Architectural critic John Ruskin stated that a spirit of sacrifice prompts one to offer precious items5.. Ruskin however, was referring to more noble materials than those that composed the Flatiron and certainly on a much smaller scale. The sacrifice in the case of the Flatiron were the steel beams all perfectly cut to size, it was the prefabricated panels that clad the exterior and also the thousands of windows that are the hallmark of all skyscraper facades. This new form of commercial and material sacrifice was perfectly suited to the icon that it created. The Flatiron legitimized this exchange at a scale that was in step with the explosive growth of the time period. The Flatiron advertised that whoever could pay and had access to a labour pool could have a tower of their own made to fit any site. It is in this sense that the Flatiron is an icon, because it became a prototype of a new kind of building- one that was a sign and a signifier of capitalism.

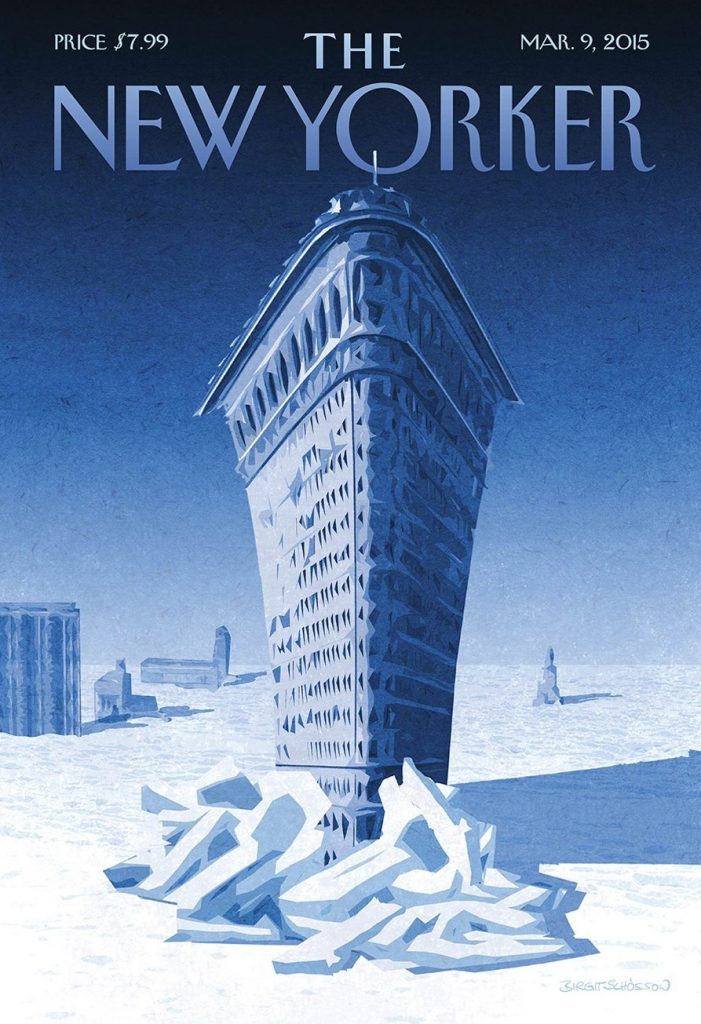

Schossow, Birgit. 2015. “Flatiron Icebreaker.” The New Yorker.

The Flatiron building captures and broadcasts the spirit of the age, its profile is often compared to the hull of a great ship cutting through the sea, an image New Yorkers would have been quite familiar with given the constant influx of immigrants and travelers. New Yorkers embraced the Flatiron as belonging to them. Even when it was rejected by critics and experts the locals flocked to the building and filled its offices and shopped in its ground floor market, known as the cowcatcher (a reference to the device that is mounted to the front of trains to stop cows from derailing them- yet another familiar image to people of that era). Furthermore, the Flatiron district was a busy commercial area full of offices and shops, so it was always in the public’s periphery. As such the building was quickly accepted into the urban fabric of New York City. The acceptance of the Flatiron as a part of the city also legitimizes its core identity as a “machine to make the ground pay6.”

The first critical reviews of the Flatiron remarked upon its impressive construction materials and building techniques. However, critics were unimpressed with the building and many considered it grotesque7.. The negative reviews did not deter the public from embracing the Flatiron, it was immediately popular and became a sight to see in New York. The public embrace included their renaming of the building. It was originally intended to be called the Fuller building8., but it’s name became the Flatiron instead. This is an interesting phenomenon when properly considered. The iconic tower could demand money, privileged space and people to inhabit and maintain it but it could not retain it’s chosen name. Perhaps this is a way that people exert subconscious resistance against overwhelming powers. In any case the Flatiron was to become a part of the canon of important buildings and also the fabric of New York city.

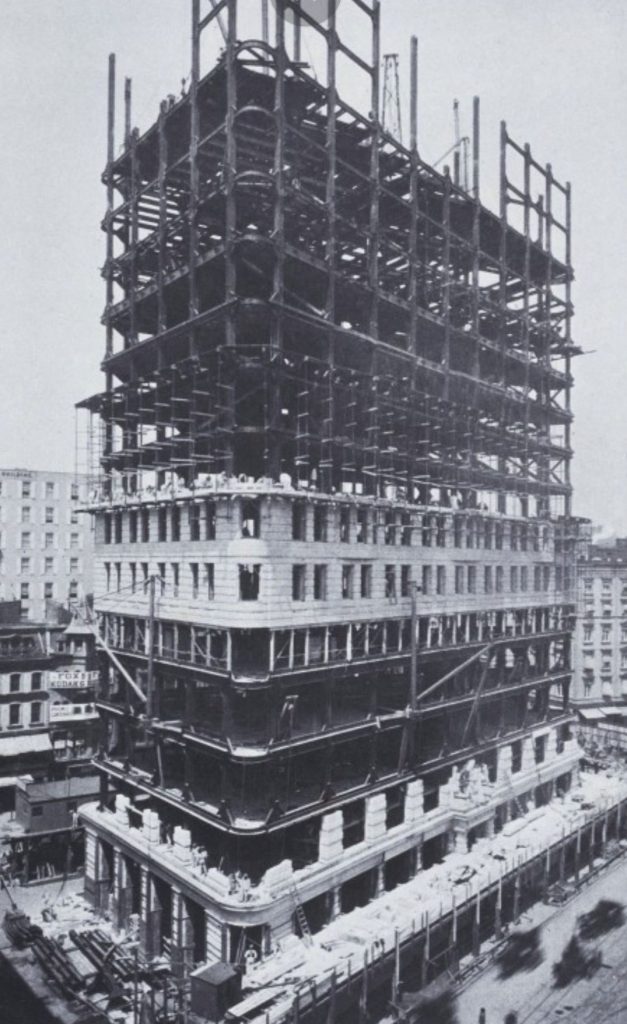

Many offices chose to be headquartered in the Flatiron, including the Fuller construction company who were the early innovators of steel skyscraper construction. This expertise allowed them to erect the Flatiron in an amazingly short amount of time given its size.

c.1901. New York: Flatiron Building: Ext.: view of construction.

This is impressive to investors because it means that they will be collecting the returns on their investment quickly. The skyscraper was a natural next step for the colonial-extraction mindset. Steel rails across the land to serve the markets and steel rails to the sky to make it pay as well. The Flatiron became more than a building full of office space, it was also an advertisement to other investors that they too could have a skyscraper in as little as two years. And if done correctly it would be accepted by locals so it could pursue its purpose without protest. The success of the Flatiron was instrumental in legitimizing a new scale of urban development. It also bound the architect to the desires of capitalism. To quote Elizebeth Yarina “The work of architects typically relies on clients who can afford the large sums of investment associated with custom design and construction; however, as architects serve increasingly global, speculative developers in a neoliberal era, our design tools are appropriated to prop up (and solidify) rhetoric’s of growth and exclusivity at the expense of the public realm.9.” What this quote describes began in earnest with the Flatiron building.

There is a downside to having skyscrapers as icons. In recent years there have been serious pushbacks. The carbon footprint is enormous, they consume vast amounts of energy and if there are downturns in local or global economies they can lose their leases and their primary function is taken away. In the years after the great depression for example the Empire State Building was dubbed the “empty state building10.” and after the Covid-19 epidemic many office workers are realizing that they are just as productive while working at home. All of these factors undermine the promise made long ago by the Flatiron building.

Late capitalism may perhaps be the era that reverses what the Flatiron is meant to signify. Instead of unlimited expansion and profit the skyscraper will come to be seen as representative of short-sighted greed. The fact that the typology is less than 200 years old and already at risk of obsolescence reveals the problems with the mindsets that justified their creation. Furthermore architectural tastes have change significantly and some of the towers built in recent years are stylistically catered to global elites, they are so abstract in form and concept that they become literal ivory towers, set aside for billionaires, the 1%11.. This makes them icons of the unattainable.

The first review of the Flatiron stated that Fuller designed “elevations and not a building12.”. I cannot say that this was a common critique in the time of the Flatiron but it is quite common now. There are many who bemoan the current state of architecture’s mainstream. Any industry that privileges flash over substance can’t last long. Architecture will surely endure, people always need shelter, however the type of architecture ushered in by the Flatiron could be in its final stage already, only 120 years from its inception. The flatiron then can be seen as the icon of the opportunity that skyscrapers promised. It will be curious to see which tower will become the icon of their demise.

T. H. McAllister (American). ca. 1905. Flatiron Building. Place: George Eastman House.

Notes.

- National Parks Service. 1989. “National Register of Historic Places.” nps.gov. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/a71a64b9-f8d2-4468-8234-5fcc113ed190. p.9

- Lankevich, G.. “New York City.” Encyclopedia Britannica, October 23, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/place/New-York-City

- Kamin, Blair. 1992. “News CITY LEARNED LESSONS FROM ITS CATASTROPHES.” Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1992. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1992-04-28-9202070670-story.html.

- Jencks, Charles. 2006. “The iconic building is here to stay.” City 10, no. 1 (August): p.13 https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810600594605.p.13

- Ruskin, John. 1880. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. 1989th ed. New York: Dover Publications.p.10

- Parker, Martin. 2014. “Why skyscrapers show capitalism at its worst – and its most sublime.” City Monitor. https://citymonitor.ai/business/why-skyscrapers-show-capitalism-its-worst-and-its-most-sublime?page=31.

- The Architectural Record. 1902. “The “Flatiron” or Fuller Building.” The Architectural Record 12, no. 5 (October): p.530 https://usmodernist.org/AR/AR-1902-05-12.pdf.

- Brown, Lance Jay, and Dixon, David. Urban Design for an Urban Century : Shaping More Livable, Equitable, and Resilient Cities. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2014. Accessed February 1

- Yarina, Elizabeth. 2017. “How Architecture became Capitalism’s Handmaiden: Architecture as Alibi for The High Line’s Neoliberal Space of Capital Accumulation.” Architecture and Culture 5, no. 2 (August):p.242 https://doi.org/10.1080/20507828.2017.1325263.p.242

- Ahlfeldt, Gabriel, and Jason M. Barr. 2020. “The economics of skyscrapers: A synthesis.” Vox EU. https://voxeu.org/article/economics-skyscrapers-synthesis.

- Parker, Martin. 2013. “Vertical capitalism: Skyscrapers and organization.” Culture and Organization 21, no. 3 (November): https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2013.845566.p,218

- The Architectural Record. 1902. “The “Flatiron” or Fuller Building.” The Architectural Record 12, no. 5 (October): p.535

Bibliography

Ahlfeldt, Gabriel, and Jason M. Barr. 2020. “The economics of skyscrapers: A synthesis.” Vox EU. https://voxeu.org/article/economics-skyscrapers-synthesis.

The Architectural Record. 1902. “The “Flatiron” or Fuller Building.” The Architectural Record 12, no. 5 (October): 528-536. https://usmodernist.org/AR/AR-1902-05-12.pdf.

Blaut, J. M. “Colonialism and the Rise of Capitalism.” Science & Society 53, no. 3 (1989): 260-96. Accessed February 18, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40404472.

Gray, Christopher. 1991. “Streetscapes: The Flatiron Building; Suddenly, a Landmark Startles Again.” The New York Times, July 21, 1991.

Jencks, Charles. 2006. “The iconic building is here to stay.” City 10, no. 1 (August): 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810600594605.

Kamin, Blair. 1992. “News CITY LEARNED LESSONS FROM ITS CATASTROPHES.” Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1992. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1992-04-28-9202070670-story.html.

National Parks Service. 1989. “National Register of Historic Places.” nps.gov. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/a71a64b9-f8d2-4468-8234-5fcc113ed190.

Parker, Martin. 2013. “Vertical capitalism: Skyscrapers and organization.” Culture and Organization 21, no. 3 (November): 217-234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2013.845566.

Parker, Martin. 2014. “Why skyscrapers show capitalism at its worst – and its most sublime.” City Monitor. https://citymonitor.ai/business/why-skyscrapers-show-capitalism-its-worst-and-its-most-sublime?page=31.

Ruskin, John. 1880. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. 1989 ed. New York: Dover Books.

Schossow, Birgit. 2015. “Flatiron Icebreaker.” The New Yorker. https://archives.newyorker.com/newyorker/2015-03-09/flipbook/002/.

Sklair, Leslie. 2006. “Iconic architecture and capitalist globalization.” City 10, no. 1 (August): 21-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810600594613.

Yarina, Elizabeth. 2017. “How Architecture became Capitalism’s Handmaiden: Architecture as Alibi for The High Line’s Neoliberal Space of Capital Accumulation.” Architecture and Culture 5, no. 2 (August): 241-263. https://doi.org/10.1080/20507828.2017.1325263.

Pictures

c.1901. New York: Flatiron Building: Ext.: view of construction. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000198638.Schossow, Birgit. 2015. “Flatiron Icebreaker.” The New Yorker. https://archives.newyorker.com/newyorker/2015-03-09/flipbook/002/.

T. H. McAllister (American). ca. 1905. Flatiron Building. Place: George Eastman House. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/asset/AEASTMANIG_10313027738.

Unknown. 1902. Flatiron Building, N.Y.. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/asset/LOCEON_1039800457.