The British Raj Thrives due to Mayo College

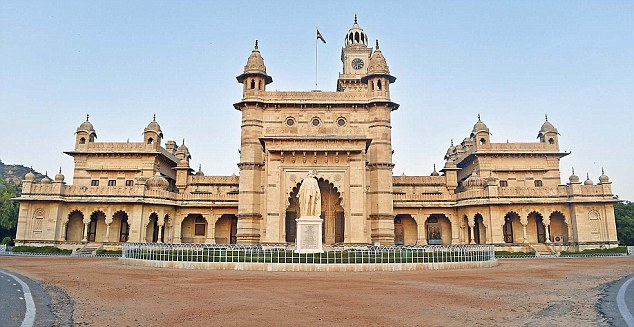

In 1875, the British founded Mayo College in the town of Ajmer, located in the Rajputana (now known as Rajasthan) area in India. During the days of the British Empire, the area of Rajputana was divided into princely states, each having its own ruler who owed allegiance to the British, and since these princes and their fellow-rulers from other states, in general, were poorly educated, the British decided to set up special chief’s colleges in various areas of the country.1 From this, a scheme to educate the elite of Rajputana, in an environment resembling an English boarding school, was devised.2 This allowed an effective imperial rule not only on troops but also knowledge as well, ultimately providing the British with more control of colonial peoples. Therefore, the Mayo College building intends to perform as a political act to benefit the British Crown by becoming a symbolic representation of the Raj triumphant through the: Indo-Saracenic style, building’s programming, and Clock Tower.

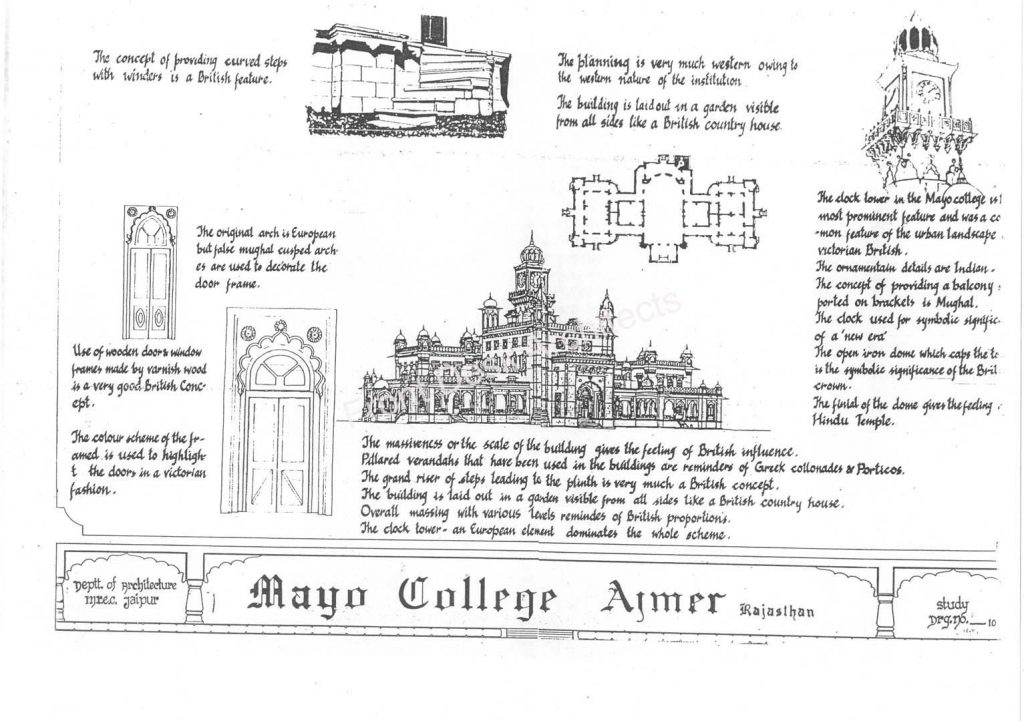

The extended controversy that took place, regarding choosing an appropriate style for the Mayo College building, explains the way the empire took shape in architecture to benefit the British Crown. This debate raged unabated for over fifty years: whether in their building in India the British ought to look to their own, or to India’s architectural traditions,3 which demonstrated a debate not reflecting concerns of aesthetics, but rather of national identity and purpose – how the Empire ought to be represented. It insisted that the chosen style must be western and that the objective of the British empire was to civilize and westernize law and education, as well as have British architecture suggest the same values. A selection of a specific style of architecture for Mayo College, and the location of components of this building, represented a conscious effort by architects to convey specific ideas of identity and politics. In other words, it can “be seen as the spatial expression of an ideological intent: the ‘capture’ and display of an Otherness that is the past, alongside symbolic markers of a ‘robust’, progressive culture, proclaiming the dawn of a new age, the future.4 This capturing and display of Otherness and the robust, represents that of bridging the difference between the two cultures – the Oriental and the Occidental. Ultimately the final style was decided and approved – the Indo-Saracenic style, and by contrast ideally suited the needs of British colonialism and benefited the British Crown. In it, not only the distinct “Hindu” and “Saracenic” forms are melded, but the British self-proclaimed masters of India’s culture.5 Indo-Saracenic thus found its widest application in buildings meant for Indians, but the content and meaning of the structure were defined by the colonial ruler. As a result, with the melding of these forms, the British believed that the imperial power managed to bring harmony among the Indians that were communally divided, placing them in a position of greater control of how India would be governed, and indirectly portraying this control through architecture.

The creation of a system of ‘public schools’, such as Mayo College, for royalty and nobility in India came with advantages for the British Crown. With customary idealism, it was seen that the education of the young rulers and nobles would serve as a cure for the secret ills of native India.6 Thus, signifying that implanting Western liberal ideas would transform states, making the establishment of public schools an attempt at indirect rule; meaning that the Indian public school system was intentionally created with imperial calculations, ethnocentric self-confidence, and well-meaning benevolence. Even in its more socially restricted form, the early Indian public school began to showcase the cultural diffusion of an educational ethic arising out of imperial conquest.7 In the internal organization of the schools, the British clung faithfully to the familiar ‘educational blueprint’ which served the upper classes in England.8 Eton in England was an example of a British school, one that is often compared with Mayo College, as Mayo College most resembles and is sometimes referred to as the Eton of India. Similarly, to Eton, private tutors were a feature at Mayo College and served as an instrument for British rule, which had to be approved by the Government and was frequently selected by political officers.9 This means that the British had ultimate control in curating how these sons of elite families would develop habits, actions, ways of thinking, and beliefs, regardless of the Indian language and culture maintaining a strong presence, English and Western traditions were still highly prioritized in the college. Mayo College eventually fully resembled an Indian Eton and functioned like one too, ultimately shaping young elites to align more with British ideologies and values, that would become advantageous to the British over time.

Mayo College’s Clock Tower is a pre-eminent symbol of British technology and the Raj, which performs to benefit the British Crown. During the Raj, clock towers could be found in almost all Indian towns, usually near administrative centres at important crossroads, which experienced a significant British presence.10 The colonial clock tower had an evident connection to the British with its embedded relation to the system of cultural and political meanings that defined and animated the Raj. With the insertion of a clock tower into a mix of diverse architectural styles, the clock tower appears to ‘control’ the ‘Oriental architecture’ surrounding it.11

Mayo College Clock Tower, stands as a prominent and articulate symbol of the ‘rational’ West, becoming a way of direction for the gaze towards various vantage points far above its surroundings, while also representing the British authority from afar. This height is more exaggerated from the asymmetry of the tall, narrowness of the Clock Tower and the shorter, robust design of the rest of the building – it elongates the tower and adds to the appearance of high importance and power. In addition, the relatively stark, unadorned appearance of the Clock Tower, which contrasts the effusion of styles that characterize the architecture surrounding it, can be viewed as a fragment between the colonial representation of the self and its Others – the Occidental and the Oriental.12 By stating this, the ‘self’ essentially towers over the Other; it controls, instructs, normalizes, persuades and even though the proximity of its presence, it reflects the distance between the colonizers and the colonized and the continual attempt at keeping a distance. This distance can also be seen through how “the British had always railed against the laziness and lethargy of their Indian subjects” and with the hourly chimes, the clock reminded students and passersby, not only of the supremacy of the Raj but the virtues of punctuality.13 Mayo College’s Clock Tower becomes a symbolic medley of British rule and insists upon the regular efficiency of the modern world that is ruled by systems like time clocks and technological devices that when compared to the Oriental, instantly reigned more benefits to the British through the power it portrayed from cities away.

Under the British Raj, the development of Mayo College was strategically planned for political gain in favour of the Occidental through the decision of implementing an Indo-Saracenic style to the building, the way the college functioned, and the significance of the Clock Tower. The British believed to have provided the divided community of Indians with harmony with the Indo-Saracenic style and in turn benefitted themselves by advertising the West through this style, they gained control over young elites with their ability to alter their perspectives through the ‘public school’ systems and created a constant hourly reminder of their power and modern-thinking with a clock tower visible from a city away. Overall, the British used these aspects in means to represent power and supremacy, and to connect to the masses of the colonized Indians and symbolize their blatancy of rule.

Notes

1. McGreal, Shirley Pollitt. “a History of Mayo College, Ajmer, India, 1875-1971.ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1971: 8.

2. Metcalf, Thomas R. “Architecture and the Representation of Empire: India, 1860-1910.” Representations (Berkeley, Calif.) no. 6 (1984): 37-65: 45.

3. Metcalf, Thomas R. “Architecture and the Representation of Empire: India, 1860-1910.” 1984: 37.

4. Srivastava, Sanjay. “The Marble Mirage: Constructing the Orient.” In , 50-61: Routledge, 1998: 40.

5. Metcalf, Thomas R. “Architecture and the Representation of Empire: India, 1860-1910.” 1984: 50.

6. Keen, Caroline. “The Power Behind the Throne: Relations between the British and the Indian States 1870-1909. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2003: 76.

7. Mangan, J. A. “Eton in India the Careful Creation of Oriental ‘Englishmen’.” In , 122-141: Routledge, 1998: 141.

8. Keen, Caroline. “The Power Behind the Throne.” 2003: 109.

9. Keen, Caroline. “The Power Behind the Throne.” 2003: 110.

10. Srivastava, Sanjay. “The Marble Mirage: Constructing the Orient.” 1998: 41.

11. Srivastava, Sanjay. “The Marble Mirage: Constructing the Orient,” 1998: 42.

12. Srivastava, Sanjay. “The Marble Mirage: Constructing the Orient,” 1998: 49.

13. Metcalf, Thomas R. “Architecture and the Representation of Empire: India, 1860-1910.” 1984: 56.

Works Cited

Keen, Caroline. “The Power Behind the Throne: Relations between the British and the Indian States 1870-1909. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2003.

Mangan, J. A. “Eton in India the Careful Creation of Oriental ‘Englishmen’.” In , 122-141: Routledge, 1998.

McGreal, Shirley Pollitt. “a History of Mayo College, Ajmer, India, 1875-1971.ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1971.

Metcalf, Thomas R. “Architecture and the Representation of Empire: India, 1860-1910.” Representations (Berkeley, Calif.) no. 6 (1984): 37-65.

Srivastava, Sanjay. “The Marble Mirage: Constructing the Orient.” In , 50-61: Routledge, 1998.

Images

Cover Image. Bureau, News Mobile State. “Top Boarding School Student Alleges Sodomy by Seniors.” Newsmobile. August 02, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://newsmobile.in/articles/2018/08/02/top-boarding-school-student-alleges-sodomy-by-seniors/.

Figure 1. Ahsan, Omar. “Mayo College, Ajmer.” Flickr. November 08, 2011. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.flickr.com/photos/56237211@N05/6325314490.

Figure 2. Measure Drawings of Mayo College -Ajmer.III – Printable Version. Accessed April 23, 2021. http://frontdesk.co.in/forum/printthread.php?tid=444.

Figure 3. “A J M E R India 2008 Mayo College: Ferry Building San Francisco, Ferry Building, R India.” Pinterest. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/293930313154613218/.