Top: View into the collection from the entrance ramp.

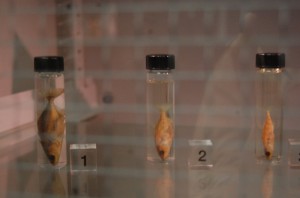

Bottom: A peak into drawers & windows of the collection.

When you enter the Beaty Biodiversity Museum, the rows and rows of black cabinets and drawers can seem overwhelming. A casual stroll through the museum offers only a brief glimpse into what the collection holds. Visitors often wonder: What is behind the black doors? What scientific treasures hide among Vancouver’s best collection of weird things in drawers? And, most importantly, why do we have all of these dead things?

It can be hard to think of dead creatures holding information, but imagine the specimens like books and the museum like a library. Each book contains unique information and a different perspective on the world. Recently, some scientists have suggested that collecting specimens to add to museums is an out of date practice that puts many species at risk of extinction. They say that researchers should instead take photos, sound recordings, and small tissue samples to gather information. More than 100 scientists wrote a response to express their disagreement and discussed the research and societal benefits that museums specimens provide.†*

Here are just a few ways collections at museums, including the Beaty Biodiversity Museum, have been used in biological research.

- The feathers of birds contains clues of the food it ate as isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen that can help researchers know where the bird migrated to during its lifetime. Since a museum stores information from many birds, scientists can look for changes over time.

- Fish collected from a lake in British Columbia and stored in the Beaty Biodiversity Museum revealed to Dr. Dolph Schluter that these sticklebacks were some of the newest species on Earth, evolving right here in BC!

- The Spencer entomology collection at the Beaty contains a large collection of jumping spiders mainly due to the collecting work of Dr. Wayne Maddison. He has repeatedly used the spiders in the museum to understand their evolutionary history.

Left: Birds from the museum displayed as they are placed inside the cabinets. Right: Species trio of sticklebacks.

A look into the jumping spider collection (Araneae: Salticidae). Also, check out a video here of Dr. Wayne Maddison collecting spiders in Ecuador.

The Beaty Biodiversity Museum uses its collection to inspire an understanding of biodiversity through education and research, but natural history museum collections can also provide information about public health concerns. For example. millions of mosquitos that have been collected and stored in museums are able to offer researchers insight into fatal and rapidly progressing mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and West Nile. Researchers also use museum collections to set a baseline for certain environmental contaminates like mercury in fish. In the 1960’s, museum collections were crucial in revealing the link between DDT pesticide use and bird declines, which helped put a stop to the widespread use of harmful pesticides. ‡

See? The museum is more than just dead stuff in drawers! Biological collections are often used in ways the original collector never imagined.*

So, the next time you wonder through the halls of the Beaty Biodiversity Museum, take a closer look at what you see. Imagine the bones, antlers, skins, bugs, fishes, shells, and fossils as a researcher would: untapped knowledge. With this perspective in hand, Vancouver’s best collection of weird things in drawers, becomes Vancouver’s best collection of knowledge in drawers.

The focal of the Beaty Biodiversity Museum: a blue whale!