Thomas King’s novel Green Grass Running Water contains a peculiar intersection in the character of Doctor Joe Hovaugh. The novel is full of references (of varying degrees of subtlety) to historical and literary figures, from General Custer (Latisha’s ex-husband George and his jacket) to Louis Riel (Louie, Ray, and Al) (Flick, 2013). Joe Hovaugh appears to evoke the Christian Jehovah: their names are nearly homophonous, and he is introduced in the novel contemplating his garden and facing to the East, the direction of new beginnings in Cherokee symbolism. At the same time, he is unmistakeably linked to the work of Canadian scholar and critic Northrop Frye: late in the book (p. 389), he is depicted “turning [his] chart… literal, allegorical, tropological, anagogic” – the same categories that Frye employs in his theoretical work Anatomy of Criticism. Rarely is a critic hailed as a creator, still less a creator of the universe. But when considered in the context of King’s motif of clashing mythologies, this incongruity begins to make sense.

In The Bush Garden (2011), Northrop Frye describes Canadian identity as that of a nation that has failed to assimilate the vastness of its wilderness, creating a “garrison mentality” against the indifference and peril of nature. He offers a three-stage process (p. 221): “English Canada was first a part of the wilderness, then a part of North America and the British Empire, then a part of the world;” but it went through these too quickly to find its identity at each step. In other words, this new Canada is a country not in ownership of its own backyard; and in a similar way, Frye’s caricature in the novel is fixated on nature but does not engage with it. Hovaugh is always looking out of windows, whether from the desk of his clinic or the driver’s seat of his Karmann-Ghia – or the Cafe in Blossom: “It was raining outside and it looked as though it was going to be gloomy for a while. And disorganized.” (p. 314, emphasis mine.)

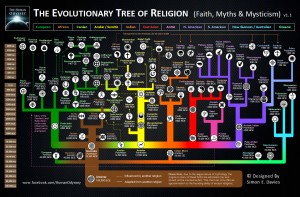

But Frye’s summation of Canada does not account for any First Nations perspective; it simply does not enter the question for him. As with the observations of Asch (2011) and King (2004) that Canadian scholarship places the beginning of Canada’s history at the moment of European arrival, thereby minimizing the vast preceding timespan, Hovaugh’s arrival in Canada in the novel is really two arrivals: the European-style academic, and the Christian Creation myth. But as King’s telling makes clear, the Christian mythology that European colonization brought to Canada was a fragile foreign bud compared to the spiritual figures that lived there already. That is why Jesus, God, and various figures of English literature squabble presumptuously with Indigenous spiritual figures such as First Woman (Cherokee), Changing Woman (Navajo), Thought Woman (Pueblo), and Old Woman (Blackfoot) in the spiritual retellings that shadow the main narrative.

Thus, Hovaugh represents a Canadian consciousness that appeared late in the cultural history of the land and yet presumes to insert itself at the beginning. Frye also has little compunction in drawing an unqualified distinction between the “sophisticated” colonial culture and the “primitive” Indigenous one. Likewise, Hovaugh says that “In ancient times… Primitive people believed in omens,” but “What they thought were omens were actually miracles.” (p. 238) A seemingly frivolous distinction, unless considered in the context of European colonization and the mythological canon it carries.

Asch, Michael. “Canadian Sovereignty and Universal History.” Storied Communities: Narratives of Contact and Arrival in Constituting Political Community. Ed. Rebecca Johnson, and Jeremy Webber Hester Lessard. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2011. 29 – 39. Print.

Austgin, Suzanne. “Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony and the Effects of White Contact on Pueblo Myth and Ritual.” Hanover College History Department. Hanover College. Spring 1993. Web. June 24, 2015.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. June 24, 2015.

Frye, Northrop. The Bush Garden; Essays on the Canadian Imagination. 2011 Toronto: Anansi. Print.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

King, Thomas. “Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial.” Unhomely States: Theorizing English-Canadian Postcolonialism. Mississauga, ON: Broadview, 2004. 183- 190.

“Changing Woman – A Navajo Legend.” Native American Legends. FirstPeople.us . n.d. Web. June 24, 2015.

“The Legend of the First Woman – A Cherokee Legend.” Native American Legends. FirstPeople.us . n.d. Web. June 24, 2015.

“Old Man and Old Woman – A Blackfoot Legend.” Native American Legends. FirstPeople.us . n.d. Web. June 24, 2015.

.jpg)