I will be investigating extra-textual connections in the assigned section pp. 222-229 in Green Grass Running Water. It corresponds to pp. 265-274 in the 2007 edition that I have, beginning with television store owner Bill Bursum thinking to himself and being teased by Coyote. It continues through an encounter between Thought Woman and “A. A. Gabriel” and ends with an exchange between the four elders and Coyote where Coyote starts a rainstorm with a dance.

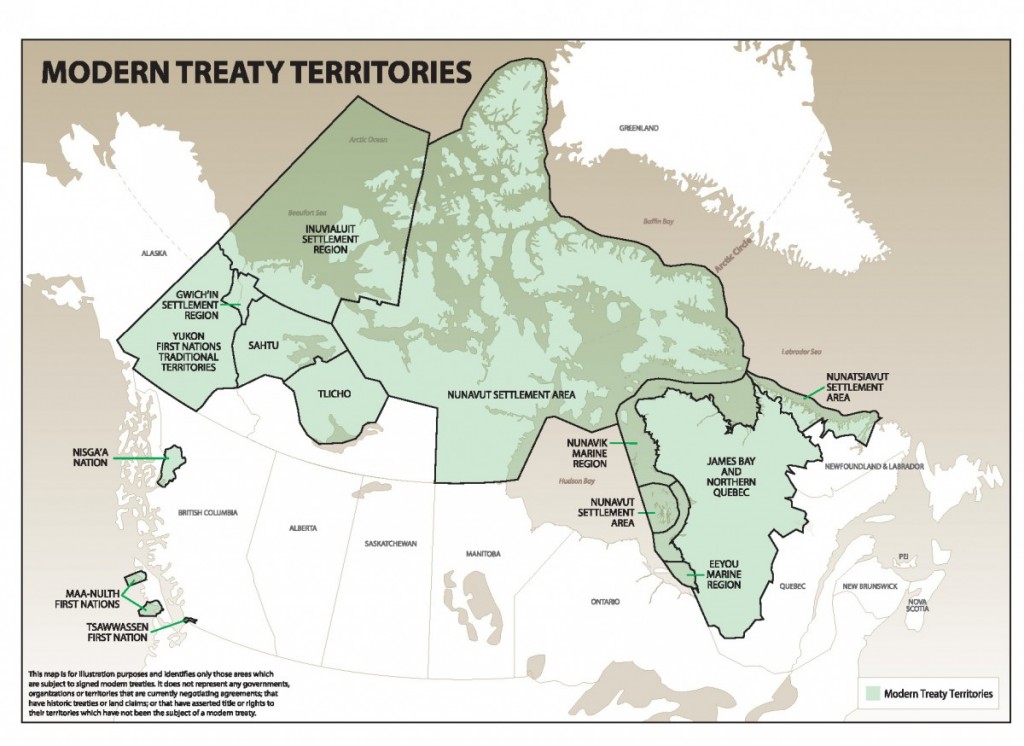

Bill Bursum’s thoughts do not include any significant direct references, although it does mention Eli Stands Alone’s cabin being in “the wrong place” (p. 267) and Bursum’s plan to pick out “the best piece of property on the lake” (p. 266) even before said lake existed. The lake was to be created by the dam, which is a symbol of technological progress. Bursum’s attitude toward the lake and the cabin are symbolic of the colonial attitude toward progress as a good and inevitable force, sure to sweep away everyone such as the Natives who fail to conform to it.

Thought Woman’s segment is much thicker with allusion. Thought Woman washes up on shore and meets A. A. Gabriel – the Arch(A)ngel Gabriel. Running through this segment is the conflation of Christian religion with state authority. Gabriel introduces himself with a card that says “Canadian Security and Intelligence Service.” The other side says “Heavenly Host.”

The card proceeds to sing “Hosanna da,” which could be interpreted as a slight garbling of “Hosa-anna” as it is usually sung. Coyote comments on this and the narrator corrects him with the card’s real song: “Hosanna da, our home on Natives’ land.” (p. 270) Again, a song of religious (Christian) importance is intentionally blurred with a song of national (Canadian) importance.

Despite the many allusions to his divinity, Gabriel has the appearance and tone of a government official, possibly a bureaucrat or customs or immigration officer. He records Thought Woman’s name as Mary; as Flick’s reading notes remind us, “Church and government officials re-named First Nations individuals with familiar, especially Christian names.” Hence the name has a dual role as an allusion to colonial history and in the next passage where Gabriel appears to try to induct her into the actual role of the Virgin Mary.

Gabriel attempts to photograph her stepping on the head of a snake, in reference to many representations and statues where she is depicted doing exactly this. The snake is supposed to represent the Devil, and hence this act is symbolic of her freedom from sin because of Immaculate Conception. (Historically, it may also be connected to a translation error.)

One very interesting detail of this passage is that, of the four observing the scene, only Gabriel sees the snake. The others all see Old Coyote instead. This may suggest the existence of two distinct perceptive worlds. In Gabriel’s, the snake represents sin and nature simultaneously, and hence the sin of nature; meanwhile in the Native worldview presented by King, Old Coyote represents the inscrutability and indifference of nature. Gabriel arrives on the narrative scene with a highly unusual and seemingly absurd perspective which he then tries to impose on others.

Finally, Gabriel tries to impregnate her, presumably so she can give birth to Jesus. The scene is suggestive of sexual coercion. When Thought Woman refuses to be involved and says no, Gabriel says: “You really mean yes, right?” (p. 271). I think this alludes to the sexual commodification of Native women which continues to afflict Canadian society. Gabriel attempts to rob Thought Woman – first of her name, then of her nationality (she is treated like an outsider, interrogated on her connection to the American Indian Movement, and implicated in smuggling), then of her spiritual role, and finally of her sexual agency. Thought Woman reacts to all of these affronts with indifference.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. June 24, 2015.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

Tan, Julian. “Statue of Mary Stepping on a Snake.” Questions and Answers. CatholicJules.Net. September 2, 2010. Web. July 9, 2015.

.jpg)