“What Wing Sing Says” by The Daily Witness, Tuesday, July 10, 1894

By: Deanna Fitzgerald

Wing Sing was a prominent member of Montreal’s early Chinatown. Born around 1880 and hailing from China, Sing traveled to Canada during the early 1890s for a chance at economic prosperity (“Canada Records,” Familysearch). At the time of his arrival in the late nineteenth century, Montreal was an attractive location for Chinese immigrants because of its affordability and commercial opportunities. The completion of the Canadian Pacific Railroad in 1885 made Montreal increasingly accessible to newly-arrived Chinese immigrants, prompting newcomers such as Sing to travel to Quebec and join the growing diaspora of Chinatown.

At an incredibly young age, Sing began his journey towards commercial success with a laundry business located at 699 Notre Dame Street (“Sing Wing,” Canada, City and Area Directories). Two years later, Sing is noted as both a merchant and hotel keeper for a hotel located on Lagauchetiere Street, a job he shared with fellow Chinese man, Sam Kee (Eaton, “Girl Slave in Montreal,” The Daily Witness, 1894). Alongside being business partners, Sing and Sam Kee demonstrated a friendly familiarity as two of Chinatown’s leading businessmen, with Sing even attending Sam Kee’s wedding banquet in December of 1893 among many other illustrious Chinatown residents (“Sang Kee’s Banquet,” Montreal Daily Herald, 1893). By mid-1894, Sing had also opened his own company aptly named the “Wing Sing Company” on 15 St. Lawrence Market Street, with the purpose of providing “Japanese and Chinese fancy goods” for Chinatown consumers (“Sing Wing,” Canada, City and Area Directories). His skill as a businessman is reflected in his reported earnings from a 1901 census: approximately $600, nearly twice as much as other workers in Chinatown at the time (“Canada Records”)!

Sing was no stranger to legal encounters. In early 1894, reports in The World newspaper accused Sing’s company of being a “rendezvous…for dozens of Chinamen who live in the various laundries of Montreal while waiting to get across the border” into the United States (“What Wing Sing Says”). Following the exclusion of Chinese immigration from the United States in 1882, immigrant smuggling became an infamous source of riches for those with the resources to sneak Chinese people across the border. Responding to reporters from The Daily Witness newspaper, Sing vehemently denied the claims published by The World, which also indicted Sam Kee and Lee Fee as fellow smugglers (“What Wing Sing Says”). The three of them were notoriously referred to as the “Wing Sing Gang.” Sing discredited associations with both men regarding any kind of smuggling operation, calling upon his reputation as being “highly respected” by “the Chinese in Montreal [and] by many English-speaking people” to differentiate himself from Lee Fee in particular, who had been arrested for smuggling charges in mid-1894 (“What Wing Sing Says”). Sing repudiated the claims as mere suppositions and the case was left unresolved (“Montreal Chinamen Interviewed,” The Daily Witness, 1894).

“The Petition of the Undersigned” from Archives de la Ville de Montreal, November 26, 1900

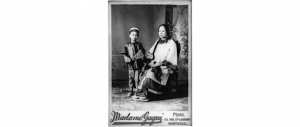

Outside of his career, Sing led a quiet personal life. His wife, referred to only as Mrs. Wing Sing in newspapers, followed him to Montreal around 1892 as one of the first Chinese women to live in Chinatown (“Montreal Chinese,” The Daily Witness, 1904). According to The Daily Witness, she took up a domestic lifestyle while Sing performed the majority of business duties as a hotel keeper and goods merchant. The two had a son together around the mid-1890s, and a photograph survives of Mrs. Wing Sing and their son wearing traditional Chinese robes as pictured below. There are no photographs of Wing Sing himself, who passed away on January 26th, 1903 due to an unknown cause and was buried in the Mount Royal Cemetery in Montreal (Find a Grave, Cimetière Mont-Royal). His wife outlived him for over two decades, passing on December 14th, 1928 and probably leaving behind their son, who likely remained a driven business opportunist much the same as his father (“Wing,” Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records).

“Mrs. Wing Sing and Son, Montreal, QC, 1890-95” by Eugénie Pilon, McCord Collection / Public Domain

Works Cited

“Canada records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSS1-GS5P-B?view=index : Feb 7, 2025), image 2821 of 5000.

Eaton, Edith. “Girl Slave in Montreal: Our Chinese Colony Cleverly Described, Only Two Women from the Flowery Land in Town.” The Daily Witness, 1 May 1894, pp. 10.

Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/108949617/wing-sing: accessed February 3, 2025), memorial page for Wing Sing (unknown–26 Jan 1903), Find a Grave Memorial ID 108949617, citing Cimetière Mont-Royal, Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada; Maintained by Headstone Genealogist (contributor 46999396).

“Montreal Chinamen Interviewed: The ‘World’ Story Does Not Unduly Excite Them.” The Daily Witness, 9 July 1894, pp. 1.

“Montreal Chinese: Six of Them Now Have Their Wives Here.” The Daily Witness, 19 March 1904, pp. 10.

“Sang Kee’s Banquet.” Montreal Daily Herald, 20 December 1893, pp. 8.

“Sing Wing.” Canada, City and Area Directories, 1819-1906.

“What Wing Sing Says: One of the Accused Montreal Chinamen Speaks to the ‘Witness’.” The Daily Witness, 10 July 1894, pp. 1.

“Wing.” Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968.