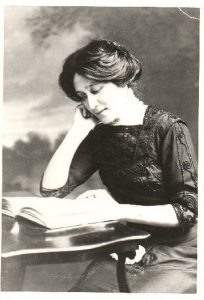

Figure 1: Two-year-old George with his mother Chu Shee and sister Avis (Wm. Notman & Son)

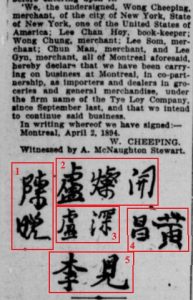

George Sang Kee was born on the 29th of September, 1895, to Ho (Haw) Sang Kee and Chu Shee, a prominent Toysanese couple in Montreal, Canada. Described by Edith Eaton in the Montreal Daily Star as “the first pure Chinese child ever born in this city,” the infant George received notable attention from the press, a fact indicative not only of his father’s status as a successful business owner and influential figure in the Chinese community, but also of the novelty of more domestic Chinese life in a community comprised almost exclusively of men (“A Chinese Child Born”). George’s mother, referred to in contemporaneous newspapers as “Miss Chu Shee,” sometimes “Miss Chu See,” and later as “Mrs. Ho Sang Kee” or “Mrs. Sam Kee,” travelled as a bride-to-be from China to Montréal in Fall 1893. Two years later, George was born in Ho Sang Kee’s hotel on rue de la Gauchetière Street West, at the very heart of what would eventually become the city’s Chinatown.

From the moment of his birth, George would not have wanted for companions or caretakers. Twelve-year-old Chu Kee, a girl recorded in the Register of Chinese Immigrants to Canada, 1886-1949 as “Jew Guey,” would have been present among the intimate gathering to celebrate Sang Kee’s newborn son that day on rue de la Gauchetière. While a number of newspapers refer to Chu Kee as Chu Shee’s “slave girl,” Edith Eaton notes that the Chinese customarily “look[ed] upon slaves as family” (“Girl Slave in Montreal”). Indeed, an 1893 issue of The Montreal Star presents Chu Kee as Sang Kee’s “little eight-year-old daughter” (“Sang Kee and Miss Chu See”). In addition to the sister figure that Chu Kee likely stepped into as an older child in the family, George would have also grown up among the many associates and acquaintances of the Ho household. Wing Sing and his wife, in particular, appear in the news as close friends of the family, and in a publicized event of an otherwise private affair, one visiting friend from Boston, referred to as “Mrs. Moy Dong Fat,” is seen accompanying Mrs. Ho Sang Kee, Chu Kee, and George to have their family photographed. George eventually gains five sisters and brothers: Avis, Charlie, Grace, Florence, and Henry. Between his proud father and mother, their growing family, and a remarkable, transnational network of friends and associates who frequented their home, George Sang Kee would have found himself in a world of thriving kinships, both familial and otherwise.

Living with his father, mother, and Chu Kee on the top floor of their boarding house, George’s early years unfolded in peculiar contradiction, at once isolated and communal, intimate and public. Days and nights would have been punctuated with the clatter and bustle of boarders just a floor below –Ho Sang Kee relegated the sleeping quarters of his hotel to the second floor, while the first floor hosted a Chinese store with “eating and lounging rooms” (“The Chinese Colony”). Beyond the boarding house, George’s life as one of the few Chinese children in Montreal would not have proved a simple existence. Recounting the experiences of mixed Chinese American children in the late nineteenth century, Edith Eaton recalls one boy who is “persecuted for nearly an hour by a crowd of roughs” (“Half-Chinese Children”). While his own reception as a purely Chinese child in Canada is unclear, representations of George in the Montreal newspapers paid special attention to the “peculiar customs” that marked his foreignness as the first Chinese infant in the city (“‘Completion of the Moon’”). Yet even in the news, George Sang Kee emerges as a liminal figure, the “only Canadian born Chinese baby,” who at one moment is “dressed in the conventional attire of a common, everyday American baby” (“The Baby Photographed”) and at another appears clothed “à la Chinoise, in a padded gown and . . . two jackets . . . made of bright quilted pink silk” (“‘Completion of the Moon’”).

Figure 2: The Ho (Haw) family featuring children George, Henry, Grace, Florence, and Avis. From the “Collection of the late Avis H. Lee,” used with permission.

George Sang Kee was certainly the recipient of a rich cultural inheritance. At one month old, he had his hair shaved according to Chinese custom, and in the years that followed, George would have crawled and toddled along the rooms of the boarding house with the beginnings of a queue on his head. No elementary schools for Chinese children existed in the city. Instead, Chinese language school took place after school at the Chinese Presbyterian Church, where George would have learned Cantonese. George performed remarkably well at school, winning several prizes and often achieving top of his class. In keeping with the general trend of the Chinese in Montreal, Mrs. Sang Kee showed little interest in the Christian religion. George’s Christian baptism is recorded in the register of Knox Church a little more than a week before his death in 1908.

George was admitted to the Children’s Memorial Hospital and passed away at the age of twelve on March 3, 1908, after having stayed at the hospital “for some time” (“Death of Chinese Boy”). Though the cause of death is uncertain, it is possible he contracted a respiratory illness in the winter months. George was followed closely by his mother in July of the same year and is buried next to her in Montreal’s Mount Royal Cemetery.

For further inquiries, you can reach the author at lopez.camilla@gmail.com.

Updated on 3 August 2023 to include a photograph from the Collection of the late Avis H. Lee, a citation correction and additional information provided by a descendant of Ho Sang Kee.

Sources

Anderson, Delaney. “Ho Sang Kee: At the Heart of Montreal’s Early Chinese Community.” Chinese Canadians: Recovering Early Chinese Canadian Literature and History, 19 Feb 2023. https://blogs.ubc.ca/chinesecanadians/2023/02/19/sang-kee-at-the-heart-of-montreals-early-chinese-community-by-delaney-anderson/

“Completion of the Moon.” Montreal Daily Star, 23 Oct 1895: 6.

“Death of Chinese Boy.” The Montreal Gazette, 5 Mar 1908: 3.

Eaton, Edith (Unsigned). “Another Chinese Baby. The Juvenile Mongolian Colony in Montreal Receives Another Addition – It Is a Girl and There Are Schemes for Her Marriage.” Montreal Daily Star, 12 Oct 1895: 6.

—. “A Chinese Child Born. At the Hotel on Lagauchetiere Street.” Montreal Daily Star, 30 Sept 1895: 1.

—. “Girl Slave in Montreal. Our Chinese Colony Cleverly Described. Only Two Women from the Flowery Land in Town” Montreal Daily Witness, 4 May 1894: 10.

—. “Half-Chinese Children.” Montreal Daily Star, 20 Apr 1895.

Ancestry.com. “George Sang Kee.” Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2008.

—. “Sang Kee.” Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2008.

Helly, Denise. Les Chinois à Montréal 1877-1951. Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1987.

“Pneumonia is Frequent and Fatal Disease.” Montreal Daily Star, 17 Jan 1908: 11.

“Pneumonia Most Fatal During Winter Months.” Montreal Daily Star, 27 Jan 1908:6.

“Sang Kee and Miss Chu See.” Montreal Daily Star, 20 Dec 1893: 8.

“The Baby Photographed.” Montreal Daily Star, 28 Nov 1895: 8.

“The Chinese Colony.” Montreal Daily Star, 15 Jun 1895: 8.

“Vital Statistics in the City.” Montreal Daily Star, 9 Mar 1908: 6.

Ward, W. Peter and Henry Yu. Register of Chinese Immigrants to Canada, 1886-1949. 2008.

Wm. Notman & Son, Mrs. Sang Kee and her children, Montreal, QC, 1897. McCord Stewart Museum, II-120280. https://collections.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/fr/objects/142147/mrs-sang-kees-group-montreal-qc-1897