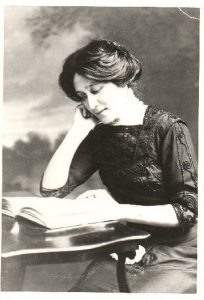

Figure 1: Edith Eaton photographed reading a book.

Edith Maude Eaton was born in 1865 in a silk-weaving town in Northern England. A few months after her birth, her Chinese-born mother Achuen “Grace” Amoy and her white British-born father, Edward Eaton, moved with Edith and her brother Charles Edward to New York, where Edward established a drug and dye business. But the growing family returned to England in 1868. When the Eatons ventured to North America again in 1872, this time with five children under eight in tow, they settled in Montreal’s Hochelaga neighbourhood.

Edith and her siblings were probably the only half-Chinese in Montreal in the 1870s and 1880s, when the Chinese community numbered only a handful of men who operated laundries. Edith recalls her brother and herself being called racial slurs. Anti-Chinese sentiment, particularly after the completion of the Canadian transcontinental railroad, led several of Edith’s siblings to “pass” as Japanese, Spanish or Mexican.

But Edith, after she and her mother were encouraged by a clergyman to visit two Chinese women new to Montreal, began to openly identify as Chinese. She began to write anonymous articles about Montreal’s small but growing diasporic Chinese community for the Montreal Witness and Montreal Star. As a half-Chinese “lady reporter,” Edith had privileged access to the intimate lives of Chinese merchants and their families: their babies’ births, their ceremonies, their marriages, and their social lives, all of which later inspired her Chinatown fiction. Edith also wrote numerous letters to the Editors defending Chinese immigrants from racist government policy such as the Chinese Head Tax policy.

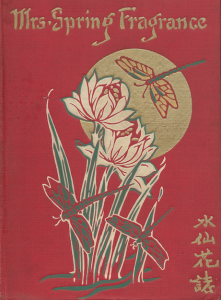

Figure 2: Cover of Mrs. Spring Fragrance, Eaton’s first and only book.

When she emigrated to the US in 1898, Edith assumed the pen name “Sui Sin Far,” which means “Chinese sacred lily,” and began to publish stories about the diasporic Chinese communities of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle, in local periodicals such as the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Westerner; missionary magazines such as The Interior, the Christian Evangelist, and the Sabbath Recorder; children’s magazines such as Children’s and Little Folks; and women’s magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal, Delineator, Designer, Good Housekeeping, Housekeeper, Holland’s, and American Motherhood. She also wrote advertising copy for railway companies and a fifteen-installment travelogue from the perspective of a male Chinese merchant “Wing Sing” for the Los Angeles Express. By 1909, her work had been published in nearly 40 popular US and Canadian magazines and newspapers.

After 1910, Edith had achieved enough success through her writing that she no longer had to supplement her income with stenographic work. She moved to Boston where she devoted the next two years to assembling the manuscript for Mrs. Spring Fragrance (Fig. 2), her first and only book, which collected seventeen short stories for adults and twenty “Tales of Chinese Children”, most of which had already appeared in U.S. magazines. When Edith died two years later in Montreal of heart disease, she left a manuscript behind that has never been found.