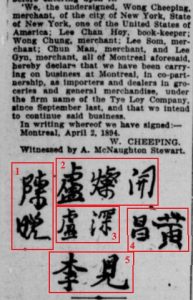

Figure 1: Tye Loy Company business agreement signed by Wong Cheeping, Chan Man (Chun Man) [1, top to bottom], Lou Chan Hoy (Lee Chan Hoy) [2, left to right], Lou Sum (Lee Som) [3, left to right], Wong Chun [4, right to left], Lee Jian (Lee Gyn) [5, left to right]; “Like a Laundry Ticket,” Montreal Weekly Witness, 18 Apr. 1894. [1]

Cheeping was not only an established figure in Montreal’s Chinese business landscape, but he was also an active member of the Chinese community in Eastern North America. While he did not have a wife with him in Montreal, he had several local and transnational friends and associates. For example, when Mr. Li Sing, another Chinese merchant, stopped in Montreal on his way to New York after visiting China with his wife in 1895, Cheeping hosted the couple at his residence on Bleury Street for three weeks (“Chinamen with German Wives”). This suggests that Cheeping had an expansive social network that extended well beyond Montreal and Guangzhou (Canton).He had established himself as a merchant in New York City as well, evidenced by his signing the agreement for the Tye Loy Company, as a “merchant of the city of New York” (“Laundry Ticket”). While he learned English and adapted to Canadian manners, which Eaton praises in “Girl Slave in Montreal,” he held on to Chinese customs and traditions, and shared his knowledge with people outside of his community. Whether it was imparting information about Chinese religions to curious reporters (“Chinese Religion”) or educating them on audience etiquette in Chinese theatres (“The Chinese and Christmas”), both of which Eaton features in her journalism for the Montreal Daily Star, his knowledge of Chinese culture was sought out and respected.

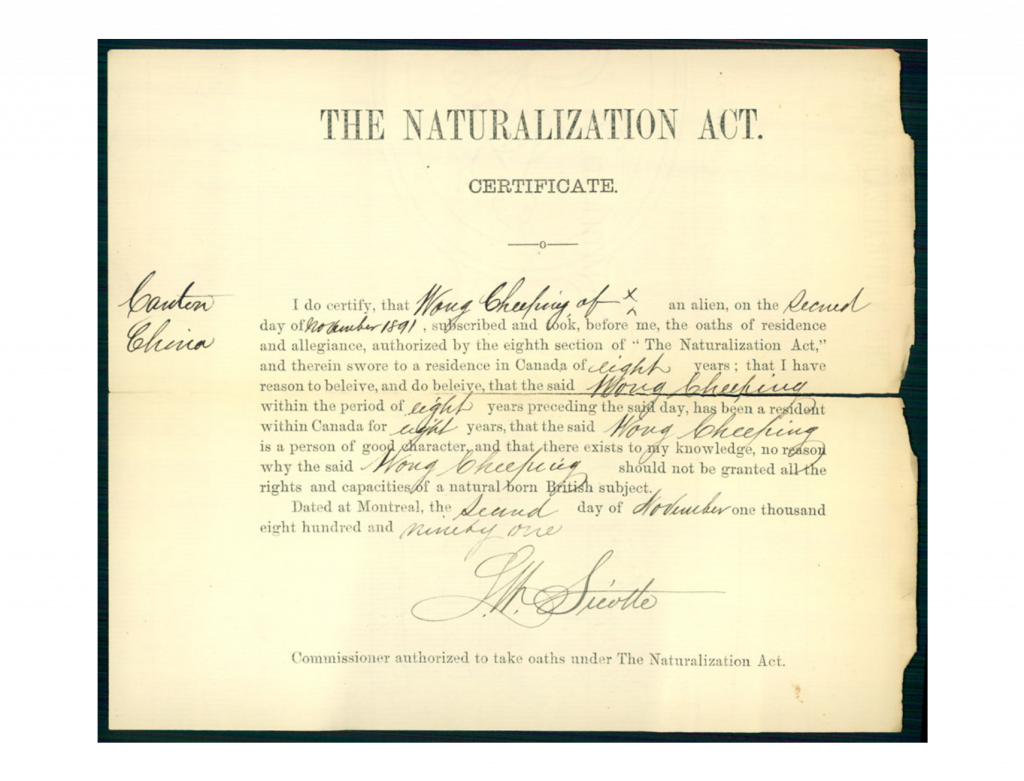

Cheeping was born in Canton City, modern-day Guangzhou, China, and immigrated to Montreal, Canada in 1883 (Naturalization Documents). He was likely born before 1865, but there is sparse documentation accessible to us of his life outside of Canada. He lived in Montreal for eight years before applying for naturalization. Attaining citizenship was an especially difficult endeavour for Chinese immigrants such as Cheeping, considering the Canadian state and society’s discrimination against Chinese people, materialized in the 1885 Chinese Immigration Act which restricted Chinese immigration to Canada by imposing a $50 duty or head tax on every Chinese person seeking entry. Having arrived in Canada in 1883, two years before the implementation of the head tax, Cheeping was able to avoid paying the fee. Even so, his application for citizenship coincided with the tax’s deployment, and the sentiments that undergirded it, the desire to keep Chinese people out of Canada, likely influenced the naturalization process for Cheeping. He was sworn in on November 2nd, 1891 (“Naturalized as British Subjects”) and received his official citizenship documents in January of 1892.

Figure 2: Wong Cheeping’s Certificate of Naturalization, Library and Archives Canada, 1892.

There are few details about Cheeping’s eight years of residence in Montreal before naturalization or the years immediately prior to his arrival in Montreal. His signature on the Tye Loy Company business agreement, of course, suggests that he lived in New York before or simultaneously with his residence in Montreal, but we have few sources of his presence in New York. Cheeping perhaps arrived in Canada having already established himself elsewhere as a merchant, an occupation that would later be exempt from the head tax, suggesting that the Canadian state sought to attract these individuals for their financial prospects. According to Eaton, Cheeping became fairly fluent in English and familiar with the social customs of Canada (“Girl Slave”) in the eight years before his naturalization, tasks that would be easier to accomplish if he were financially secure and did not have to worry about finding employment. Financial stability would have also granted him access to social circles that could teach him Canadian manners and customs. In addition, it would have allowed him to support his “bright and intelligent” sixteen-year-old cousin who attended school in Montreal (“Girl Slave”).

In 1896, Cheeping travelled back to China in the company of Sin Chow Kee and Sin Kee, two other merchants associated with the Tye Loy Company (“Briefs”), and it is uncertain whether he returned to Montreal after that trip. He handed the Tye Loy Company off to his business partner Lou Chan Hoy (“Will Bring His Wife Here”), suggesting that his trip would be a lengthy, if not permanent, return to China to rejoin his wife. From this point, traces of Cheeping’s presence in Montreal newspapers disappear. It is possible that he returned to Montreal, but it was never reported because he did not rejoin Tye Loy. Perhaps he re-established himself in New York, a part of his story on which we have even less information than the Montreal portion of his life. Or he remained in China to reunite with his wife and decided against returning to Canada, as the tax to bring his family into the nation would have been too steep. Wherever Cheeping’s path led after 1896, his departure from Canada after undergoing the lengthy and arduous process of naturalization, coupled with his vague presence in New York, presents Cheeping as a transnational figure who traversed a complex path, of which Montreal was only a small piece of the larger story.

Footnotes

- Names are translated from signatures in Hanyu Pinyin.

Sources

“Advertisers Business Classified Directory,” Lovell’s Montreal Directory, for 1894-95. Montreal, John Lovell & Son, 1894.

“Briefs.” The Gazette Montreal, 17 Mar. 1896, p. 3.

Cheeping Wong Naturalization Documents. 15 Jan. 1892. Citizenship Registration, Montreal Circuit Court, 1851 to 1945. RG 6 F3, Volume 896, File 402. Library and Archives Canada. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=citregmtlcircou&id=2213&lang=eng.

“Chinamen with German Wives.” Montreal Daily Star, 13 Dec. 1895, p. 5.

“Chinese Religion. Information Given a Lady by Montreal Chinamen.” Montreal Daily Star, 21 Sep. 1895, p. 5.

“Girl Slave in Montreal. Our Chinese Colony Cleverly Described. Only Two Women from the Flowery Land in Town.” Montreal Daily Witness, 4 May 1894, p. 10.

Helly, Denise. Les chinois à Montréal 1877-1951. Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1987.

“Like a Laundry Ticket.” Montreal Weekly Witness, 18 Apr. 1894, p. 5.

“Naturalized as British Subjects.” The Gazette Montreal, 03 Nov. 1891, p. 3.

“Sociétés et Dissolutions.” La presse, 11 Apr. 1894, p. 4.

“The Chinese and Christmas.” Montreal Daily Star, 21 Dec. 1895, p. 2.

“The Chinese Colony.” Montreal Daily Star, 15 Jun, 1895, p. 8.

“Will Bring His Wife Here.” Montreal Daily Star, 23 Mar. 1896, p. 2.