Researched and written by Cal Smith

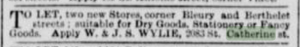

In an 1894 unsigned article in The Montreal Witness, a presumed Edith Eaton describes how Chinese laundries organized clothes. In the article, she writes, “A reporter[,] being curious to find out how this method worked, called on Wing Wah, St. Catherine street…” [1]. The 1894 Montréal Street Directory reveals that Wing Wah’s laundry occupied 2083 St. Catherine Street [2]. The property had recently been put up to let in an advertisement in the March 1893 issue of The Daily Witness. The article describes the building as “two new Stores..suitable for Dry Goods, Stationary or Fancy Goods…Apply W. & J. S. Wylie, 2083 St. Catherine st.” [3].

The Register of Chinese Immigrants to Canada lists a 35-year-old “Wing Wah” as arriving in 1891 in Vancouver aboard the Abyssinia. He came from the village of Chewking in Sinning (新寧) in Canton and his occupation was listed as a “farmer.” He paid a $50 head tax and was given a C.I. 5 No. 5859. The immigration officers described “2 large scars on[?] front head.” Presumably, Wah made his way to Montréal where he became a laundryman in Montréal’s growing Chinese community. He operated his laundry, according to the Montréal City Directory, from 1893 until 1889-1900. In 1901, he appears to have moved down the street to 1486 St. Catherine while another man, Sing Lee, took over the laundry at 2083 St. Catherine [4].

From an 1896 article entitled “A Chinaman’s Love Story” in The Montreal Star, we learn that Wah spoke both English and Chinese [5]. The article records how a Scottish woman who only spoke English and a Chinese man who only spoke Chinese fell in love. When the man wished to propose, his lack of English (and her lack of Chinese) interfered in the proposal procedures. Luckily, “The assistance of Wing Wah, a laundryman on St. Catherine St., was summoned. He acted as interpreter…” [5]. Wah’s help in the matter secured the marriage.

Working as a laundryman would have been difficult in Montréal, which was hostile to incoming Chinese [6]. There were around 200 Chinese Laundries in Montreal at the turn of the century, and the Québec government instituted restrictive tax policies that targeted them. In October 1896, The Daily Witness records a group of sixty Chinese laundrymen, including Wing Wah, gathering to contest a recently implemented yearly $50 tax on laundries [7]. Their appeal was unsuccessful, and they were each fined $10 or threatened with a 1-month jail sentence. The 1896 tax continued to exert enormous financial pressure on the Chinese laundries. On February 24th, 1900, over 100 Chinese laundrymen joined together to sign a petition that would reduce the yearly tax from $50 to $12. The petition records the difficult life of Chinese laundrymen: “as your Petitioners are all poor and unable [to afford the tax], owing to their ignorances of the languages spoken in the Country, to compete with her craftsmen in the exercice [sic] of the various trades which are practiced here, they are compelled to earn their livelihood by keeping small laundries in various parts of the City” [8]. Wing Wah signed his name on the document in a distinct ink and hand from the rest, and he lists his new address at 1486 St. Catherine [8]. The petition was ultimately unsuccessful [9].

An article in May of the same year in The Montreal Daily Star writes that about 125 Chinese laundrymen were imprisoned following the petition [9]. The article notes, “The gaol [jail] is so crowded that there is no chance for an airing in the yard.” Wing Wah is included in the article’s list of men jailed. After 1901, Wing Wah disappeared from the Montréal Directory, and the property at 1486 St. Catherine became a restaurant in 1904 [10]. Wah’s fate is unknown. The two months in jail likely shuttered his laundry. He may have joined another laundry in an attempt to thwart the laundry tax’s targeting of individual business, or he may have left Montréal.

(Laundry Chong Sing, 1911, Archives de la Ville du Montréal) [11]

Works Cited:

[1] Eaton, Edith. “No Tickee, No Washee.” Becoming Sui Sin Far: Early Fiction, Journalism, and Travel Writing by Edith Maude Eaton. Edited by Mary M. Chapman. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2016.

[2] A Street Directory of Montreal. 1894-1895, pg. 223. http://more.stevemorse.org/montreal_en.html.

[3] “To Let….” The Daily Witness. 23 March 1893, pg 2. https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3629516.

[4] A Street Directory of Montreal. 1900-1901, pg, 263. https://collections.banq.qc.ca/retrieve/13737507.

[5] “A Chinaman’s Love Story.” The Montreal Star, 28 January 1986, pg 8. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740878641/?.

[6] “19th Century.” Je Suis MTL. https://www.untoldstoriesmtl.com/en/centuries/19th-century.

[7] “The Chinese Laundries: Operation of a One-sided Law Against Them.” The Daily Witness, 28 October 1896, pg. 6. https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4666876?docsearchtext=The%20daily%20witness,%2028%20octobre%201896.

[8] “Laundrymen Petition.” Archives de la Ville de Montréal. 24 February 1900. https://drive.google.com/drive/u/1/folders/1SKAN6m_TYRmkI70ouY4zzIA55_OC4HIf.

[9] “Laundry Tax Ruins Many Celestials.” The Montreal Daily Star. 31 May 1900, pg 1. https://www.newspapers.com/image/740876821/?.

[10] A Street Directory of Montreal. 1904-1905, pg, 278. https://collections.banq.qc.ca/retrieve/13737563.

[11] Paré, Olivier. “Jos Song Long et Les Premières Buanderies Chinoises.” Encyclopédie du Centre du Mémoire du Montréal. June 2017. https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/memoiresdesmontrealais/jos-song-long-et-les-premieres-buanderies-chinoises#.

(Laundry Chong Sing, 1911, Archives de la Ville du Montréal) [11]